What killed TiVo? An architectural shift.

In 1998, as Forrester’s analyst covering the television industry, I got my first peek at TiVo, the original and most promising digital video recorder. It was an amazing device that easily recorded TV programs on a hard drive and promised to free viewers from the TV schedule forever. It was instantly clear to me that TiVo and other DVRs would usher in a new era for TV viewing.

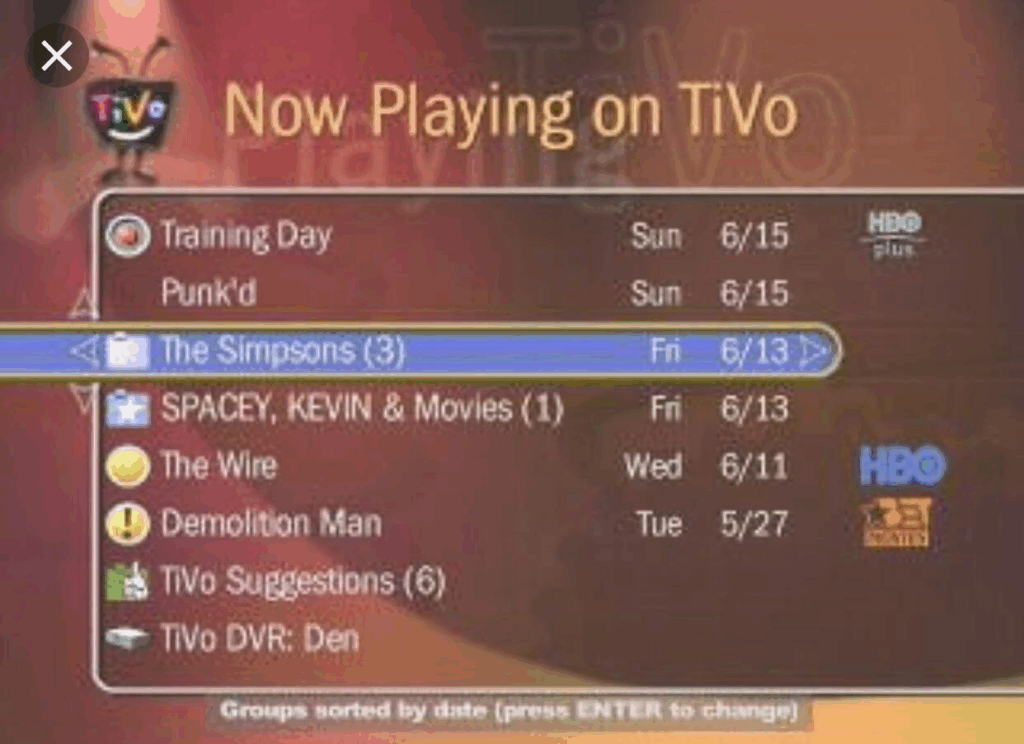

It also featured a breathtakingly beautiful interface. It was the most elegant TV device I’d ever seen, in a world where the on-screen graphics of TVs and set-top boxes were ugly and clunky and VCR recording interfaces were intimidatingly primitive. Architecturally, this was the right moment for a device that easily time shifted TV. But from a pure design standpoint, I just wanted TiVo to win. By comparison, the visuals of its competition, ReplayTV, were ugly as sin.

Tivo has just stopped selling Tivo boxes. After many years of decline, it sold its last set-top-box on September 30.

Tivo launched an architectural shift, but was swept away by another

When TiVo arrived, TV was a broadcast medium. It arrived by cable, satellite, or over the air at your house, where it was likely gated by a lame set-top box with an awkward interface and then piped to your TV. You watched programs when they were on. Time-shifting technologies like VCRs and video on-demand hadn’t really caught on.

TiVo, which recorded programs on a hard-drive, marked the beginning of the end for scheduled TV. (When I publicly predicted that, Henry Yuen, CEO of program-guide maker Gemstar-TV Guide, was so incensed that he tried to have me fired, but I was right.) The idea was irresistible, but the architecture of TV created headwinds for Tivo.

The main obstacle was those cable and satellite boxes. If you bought a standalone TiVo and you had cable or satellite, it needed to manipulate the set-top box by spoofing the infrared remote, which was kludgy and subject to errors. The obvious solution was to build the TiVo function into the set-top box, which several of the satellite operators did. Some cable operators pioneered it in their set-top boxes as well. And there was a sort-of workaround called CableCARD, which was a device from your cable operator that you could plug into your advanced TiVo model to authenticate the channels, but that worked poorly and the cable operators were understandably unenthusiastic about it.

Despite those challenges, TiVo reached millions of households. But the real architecture shift was coming: streaming, pioneered by Netflix and Hulu. Now you could get your programs directly from a broadband connection and watch them whenever you wanted with no cable box. The expensive hardware was no longer in your house, it was in a server farm somewhere way upstream.

Streaming had several huge advantages. It was an opportunity created in conjunction with the networks and program owners, so it was backed by the people making and broadcasting the programs. Unlike DVRS, it included unskippable ads (or alternatively, an ad-free subscription model with the program owners taking a cut). It was lightweight enough to build into cheap standalone set-top boxes like AppleTV and Roku, or cable and satellite boxes, or TV sets themselves. Unlike hard-drives, which eventually fail or become obsolete, streaming could keep improving with updated software and improved bandwidth.

TiVo, of course, created boxes that incorporated streaming. But with streaming connections built into all modern TV sets, it was no longer competitive. Despite its superior interface, it was out of step with the shift from scheduled, broadcast TV to streaming. It was a victim of the architecture shift.

Architecture shifts always threaten existing players

Consider some past architecture shifts that transformed markets.

When Apple and IBM created PCs in the 1970s, minicomputers and terminals became obsolete. Massive players like Digital Equipment Corporation faded away; Apple surged.

When the internet and browsers arrived in the 1990s, the world shifted away from desktop applications and software became software-as-a-service. Microsoft suffered; Google surged.

Napster became the gateway to streaming music. In the 2010s, music labels and music retailers suffered; Spotify and its competitors surged.

AI will drive the next shift. It is profound. It threatens to replace both search and apps. It’s no surprise that Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta are all over it — it’s the biggest architecture shift since digital technology began.