AI and writing; where to pitch what; Trump trashes copyright: Newsletter 30 July 2025

Newsletter 104: Any writing tool that clarifies communication is a boon, AI included. Plus Amazon licenses the Times, Trump declares IP meaningless, three people to follow and three books to read.

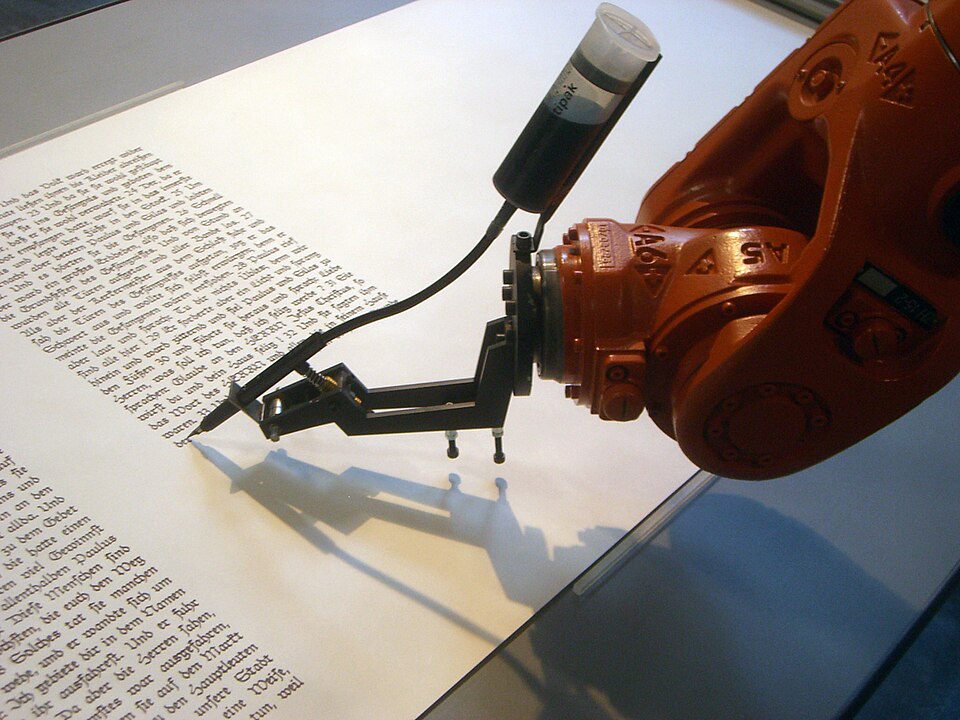

The future of human writing

A furious debate is going on now about AI-generated text. Professional writers and other humans who write feel threatened by AI, and want to ensure that no one mistakes their writing for AI-generated slop.

Now writers tell me they are avoiding the supposed “tells” of AI-generated writing, including em-dashes; AI-favored words and phrases including “delve,” “it is important to note,” and “in conclusion”; excessively even and logically repetitive sentence structure, and so on. And of course, freedom from grammatical and spelling errors.

This is a pointless battle. You, the writer, are going to lose. The creators of AI tools are well aware of these weaknesses in their text generation and are in the process of fixing them, faster than you can take note of and avoid them. Many can already be fixed with better prompts.

But more importantly, why are you even bothering?

The point of writing is to communicate. If a machine can communicate better than you can, why shouldn’t we use a machine in that capacity?

I’ll give you an example. Suppose that home inspector sends me a document, the results of his inspection of a house I am considering buying.

Is it really important that the report is written by a person? I’m sure the home inspector is just cutting and pasting elements of that report, like “oil tank shows evidence of leaking” or “wiring in bathroom not up to code.” If the inspector asks AI to create that report rather than cutting and pasting, the report still doing its job of explaining what’s wrong with the house I’m thinking of buying. Who cares who wrote the report?

I would certainly hope that there is commentary in there about unique issues about my house that they detected, but if 90% of the report is the identification and explanation of issues with standard language about them, that’s fine with me. I don’t need a hand-crafted and cleverly curated artisanal document about wiring issues.

In fact, let’s suppose that I receive the report and respond with questions, like “How common are these wiring issues and are they dangerous?” If a home inspection expert AI can respond based on its knowledge of wiring issues and codes, I don’t really care if that information was crafted (or cut-and-pasted) by a human or a machine. All I care is that it’s accurate. With appropriate links included and supervision by an actual experienced home inspector, I am sure that it could be.

My theory is that most nonfiction writing jobs are like this. They are intended to communicate something factual. They are based on a known series of facts or knowledge included within a set of data. A human expert can create them, potentially with the aid of AI. Getting them right requires human intervention and supervision. Whether you are a paralegal or a copy writer writing product descriptions or a business strategist, much of your future work is going to look like this.

It will require less of your time, because the AI will help. If you use the AI to substitute for your judgment, the writing will be worse, and people will know. If you use the AI to augment your research and productivity, the writing will be better, and people will notice that, too.

To my writer friends, before you get out the pitchforks and torches, let’s consider another use case: You are a professional writer because you’re an excellent writer. You are witty. You make unexpected connections and write in vivid metaphors. Your writing attracts attention and respect because it reflects your intellect; that intellect is what’s really responsible for the attention and respect.

If you’re good, you’re not going to be replaced, because I don’t think AI is ever going to manifest that level of intellect and wit. It is by definition only as smart as the mass of us, averaged out. It lacks judgment. That’s what people pay for and what they pay attention to.

I am currently engaged in a large ghostwriting project with one of the smartest individuals I’ve ever encountered. He chose me because I can engage with that intellect, write about his ideas in fascinating ways, and create the attention and respect those ideas deserve. He isn’t telling me not to use AI; in fact, he insists that I use it, because he doesn’t want to pay me to do rote work a machine ought to be doing. He wants an AI-enhanced professional writer, and that’s what I’m giving him.

At the top end of the writing profession, this is, I’m certain, happening repeatedly. Strategists, authors, Substack writers, and creators of white papers are leveraging AI to make themselves faster and smarter, not to substitute for rote production of generic words and paragraphs.

It’s the run-of-the-mill writing jobs that changing. And that demands a change in how we define the job of writing and how we teach people to write.

We must train all writers, in school, in college, and on the job, in the creation of meaning and engagement through writing. We should help them learn to use machines to help just as we encouraged them to use spell-check and Google search and Microsoft Word. They must learn what machines are good at and also what humans are responsible for: judgment, creativity, and wit.

Accountants using accounting software now do their jobs faster and more effectively than they did before the software existed, but they’re still ultimately responsible for supervising that work and ensuring its quality. The same is true for lawyers and paralegals filing legal briefs and financial analysts writing about corporate results. And the same will be true of all sorts of writers.

AI-written slop is lame, but it is for the most part replacing human-written slop. Slop is slop. If it’s the best you can produce, stop writing and develop some different skills, because you will be replaced.

There are plenty of arguments against the use of AI, from the stolen content it’s trained on to the energy it consumes, but the argument that we must somehow preserve the jobs of all writers is disingenuous. Machines write all sorts of things already. The only question is which things they will write in the future, and how humans will use machines to help them communicate more effectively.

News for writers and others who think

Amazon is paying at least $20 million to license quality content from The New York Times. This sort of license will keep happening at the high end even as the likes of Cloudflare enables it at the low end. AI needs access to quality content and will pay for it.

Tim Herrera shares a guide for pitching more than 100 publications. Thanks, Tim!

Dries Buytaert suggests that the automation of rote technical work will remodel the digital agency world.

The Trump administration announced a national AI plan that doesn’t address theft and licensing concerns. When reporters asked Trump about it, he said “You can’t be expected to have a successful AI program when every single article, book or anything else that you’ve read or studied, you’re supposed to pay for,” Trump said. “You just can’t do it, because it’s not doable.” Until the copyright law is changed, though, courts will have to decide what’s practical or not.

Keri Facer and Harriet Hand share an intriguing visual representation of how different deadlines feel.

Finally, the em-dash comes out to defend itself. “I am the punctuation equivalent of a cardigan—beloved by MFA grads, used by editors when it’s actually cold, and worn year-round by screenwriters. I am not new here. I am not novel. I’m the cigarette you keep saying you’ll quit.”

Three people to follow

Emmanuel Tsekleves, who has evaluated which AI tools live up to editorial standards.

Julie Broad who tells you what to do (and what to avoid) when self-publishing.

Susan Crossman BA (Hons.), MA , expert on LinkedIn strategies for nonfiction authors.

Three books to read

Every Word Matters: Writing to Engage the Public by Ranjana Srivastava (Simon & Schuster, 2025). Writing advice from the Guardian columnist and cancer doctor.

The Writer’s Diet: A Guide to Fit Prose by Helen Sword (University of Chicago Press, 2016). A brief, active book about brief, active writing.

When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows . . .: Common Knowledge and the Mysteries of Money, Power, and Everyday Life by Steven Pinker (Scribner, 2025). How “common knowledge” happens and how it drives so much of our behavior.

I agree with your perspective on AI. It’s a tool like any other, and it makes me more efficient and effective.

And therein is the key to the whole kerfuffle – AI is a tool. Most seem to be forgetting, ignoring, or hiding that fact, both writers and AI-function creators.