Writers’ secret superpower: framing the truth

In any corporate meeting, there’s (at least) one person who likes to write. That person may be you.

Everyone else sees writing things up as a chore. You don’t. It hardly seems like work to you.

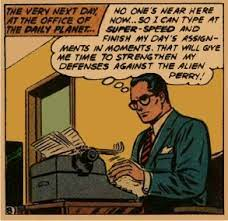

Maybe you don’t realize it, but your writing ability creates soft and pervasive influence — if you volunteer to use it.

How writing creates power

You’re planning an event. There are five slots for content, and your team comes up with eight ideas. Which ones should you move forward with?

They assign you, the writer, to make short descriptions of the content. Naturally, you make the ones you like sound best. Then they all get passed around for a vote. Guess which ones get the nod? Most likely, the ones you prefer.

It’s time to spec out a new product. Somebody has to write up the description of what it is and how it works. They assign that to you. Soon, you’ve described the product that has the features you’d like best. If that passes muster, the product will soon work the way you think it should.

(If this sounds outlandish, well, it happened to me. At a company I worked at, Mathsoft, my job was to document new features. The chief engineer — and company president and cofounder — would sit down and describe them to me. But after a while, I started to describe how things should work to him. Pretty soon, he asked me to write the feature descriptions first and then he would build what described. I wasn’t a product designer — or was I? That engineer, Alan Razdow, recently edited the Wikipedia description of the product to list me as the product’s codesigner.)

Your department needs to make a new hire. They ask you to write the job description. You include all the skills needed for the new hire to reduce your workload and make it possible for you to concentrate on the part of the work you enjoy most.

You write the minutes of the meeting. You decide which were the most important questions decided and what those decisions were. What you described is now what happened.

At Netflix, all important decisions are made starting, not with a meeting, but with a memo. The person suggesting a change must create a memo that describes the evidence for the change, the details, and the consequences. As the company says in its culture document:

We share documents internally broadly and systematically. Nearly every document is fully open for anyone to read and comment on, and everything is cross-linked. Memos on . . . every strategy decision, on every competitor, and on every product feature test are open for all employees to read.

Think about it. Don’t you think the best writers have more influence in a memo-driven culture?

Don’t abuse your power

As you can see from these examples, a writer on a team can distort decisions and contravene reality. Don’t do that. You’ll get caught, and you’ll lose people’s trust.

Do an honest job in what you write, and you’ll still win — because you get to frame things with your own perspective.

As a writer, you have a superpower. Recognize it. And use it wisely.

So grateful for subhead “Don’t abuse your power.” Wise, moral counsel.