Why you should love your tough developmental editor

Jeevan Sivasubramaniam, editorial director of the publisher Berrett-Koehler, recently wrote that if you love your editor, they’re probably not doing a good job.

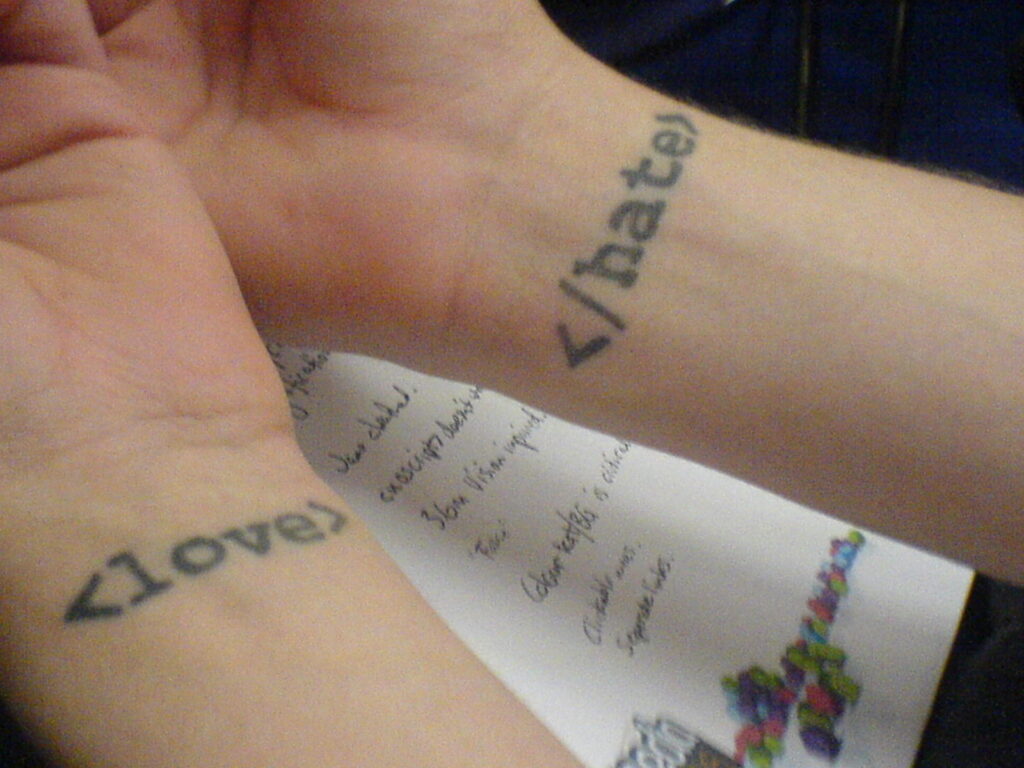

This contradicts my experience. Great writers love great editors — and hate them at the same time. It’s a strange relationship.

An analogy

Imagine that you are working with a personal trainer at the gym. And imagine this conversation takes place in your second weekly workout session.

Trainer: How did you feel after your last session?

You: A little sore here and there.

Trainer: Well, we’ll have to take it easy on you, then.

You: No, it’s no big deal.

Trainer: I’d like you to avoid all pain.

You: Umm . . .

Trainer [demonstrating exercise]: Now, let’s try some lunges. Here’s how they look.

You [attempting to mimic trainer’s movements]: Like this?

Trainer [not looking very closely]: I’m sure that’s fine.

You: How many should I do?

Trainer [sits in chair, looks bored]: However many you feel like. Let me know when you’re done.

I think we can all agree that this trainer is worthless. How would you feel about them? You might like the fact that they make the workout effortless, but if you’re even a little thoughtful, you know they’re wasting your time. You’re not learning anything.

On the other hand, the trainer who works you within an inch of your life might not be the best, either. Cruelty is not helpful, and total exhaustion to the point of injury won’t help you get stronger or more fit.

The ideal trainer makes you do some things you don’t love doing, leaves you feeling a little sore, and, most importantly, observes you closely and gives you personalized instruction based both on their expertise and what you seem to need. And if you ask them “why,” they can always explain the purpose behind what they’re recommending.

The writer-editor relationship

Here’s part of what Jeevan wrote on LinkedIn:

Whenever an author hands in a manuscript and tells me “I have had this completely worked on already by my editor,” I ask them what their opinion is of that editor. If they say “Oh, they are fantastic – the best!” then I get nervous.

I work with over a hundred editors and have worked with many more over the decades, and I have come to realize that often when an author says their editor was fantastic, it usually means that editor basically did what the author wanted and didn’t push, prod, or challenge them. And by not doing so, affirmed the author’s belief that their work was just fine.

Serious writers don’t trust editors that worship their prose. Such an editor is as worthless as the lazy trainer I just mentioned.

If you hire me (or any other really good developmental editor), this is what you’re going to get.

- I will challenge and find flaws in your main idea.

- I will identify problems in the way your book is structured.

- I will find and suggest fixes in the way your chapters are structured.

- I will point out your blind spots, where your own knowledge has created writing that will leave readers confused.

- I will question the credibility of your examples and statistics.

- I will dismantle and rewrite your paragraphs and sentences, identifying and suggesting fixes for problems like repetition, jargon, passive voice, dull sentences, grammatical errors, lack of sourcing, and so on.

Basically, if there’s anything wrong with your manuscript, from terminology to believability to expression — anything that is a weakness — I’m going to point it out and suggest a way to fix it. This is developmental editing.

Just as important — because I know you are a human being who feels proprietary about what you wrote — this is how I edit.

- I try to figure out why your writing has problems — why you did what you did — and point that out.

- I explain why what you are doing is problematic and why a different way is better. There is no mystery in what is driving my suggestions.

- Where I love what you did, I say so. Praise is free, and can help provide a psychic counterbalance to all the criticism.

- I use humor wherever possible, poking fun at the writing, the author, and myself, but in warm and loving way.

This is much more work than just editing text (and also much more work than just saying “Wow, love this, this is great.”). But it makes writers to love what they are creating and to become better writers — to grow. The result is a far better book.

Good writers love tough editors

After all this criticism, what happens. Do they hate me? After all, my job is to find fault with their creations.

Nope. Nearly all of my editing clients love me. They are, without exception, happy to act as references. They come back to me again for the next book. (They do find me difficult and challenging, but they get over that.)

When I was at Forrester, part of my job was to edit reports written by analysts who were having problems. “Send them to Josh, that should help,” was a common refrain.

While I was working with these analysts, I often heard them say “Wow, this is way more work than I ever had to do before. You are a tough editor. You’re very hard to satisfy. You keep finding new things I have to fix.”

When I was done, I often heard then say “Wow, this is so much better. I want to work with you on the next report.” After all the complaining, this always surprised me. (I rarely worked with the same analyst twice, because they’d already learned what I was trying to teach them.)

That dynamic has continued. And I want to be clear, this isn’t about me per se. It is about all tough, caring, expert editors.

Every author who works with us looks at the redline edits all over their manuscript and says, “Whew, that’s an incredible amount of work, and I feel a little hurt that you found so many flaws in what I wrote with love.”

And when we’re done, they say “Wow, that is so much better. Thank you. You made a huge difference.”

Jeevan understands

At the end of Jeevan’s post, he says this:

My suggestion to authors: Trust the difficult editor. Trust that they will challenge you to re-work, restructure, and rebuild everything, and accept that your ego may take a bruising in the process. Also, everything may take twice or thrice as long as you planned. Think of your editor like that exhausting teacher, professor, or boss you had once – the once who pushed, chided, and challenged you constantly and was, frankly, a pain in the ass (and made everything such an ordeal). You may not have even liked them, but you’d be damned if your work was the best it had ever been for their pushing and prodding. Look for that in your editor.

I believe Jeevan when he says that there are authors who seek out editors who will pamper them, and that even if they love their work being treated that way, the editor did a poor job.

But in my experience, any author worthy of the title has a much deeper and more profound appreciation of the tough editor. Yes, we make you work. But if the result is superior, that’s good for the book, and much better for you.

And to the editors out there: You can be tough without being brutal. If you edit with intelligence, skill, and love, your clients will appreciate it. They’ll come back. And even if Jeevan doesn’t believe it, they’ll like you, too.

100%.

It’s much better for the author to receive painful feedback before the book drops. At that point, there’s not much to do.

As I’ve done more ghostwriting and developmental editing work, I’ve often told my clients: I’d rather have you mad at me now than six months from now when we can’t address the manuscript’s problems.

How do you deal with that initial pushback from writers who think you are being difficult (even though that is what they’re paying you for)?

I recently had a client who became petulant when I was doing a development edit, then I started to feel guilty. How do you manage your emotions and “stay strong” as it were?

As editors, we need to develop relationships with our clients, so it feels like a rough start to the relationship, even tough I know it’s necessary.

Two things.

My tone is professional and authoritative. I talk like an expert because I am an expert.

And I always give a reason for the edit … And the reason is it’s better for the audience, the reader.

Once you’re arguing about what’s best for readers the argument becomes about logic, not ego.