How authors can work with a developmental editor

A developmental editor can help make your book better. They also cost money — and spending that money wisely demands some preparation. Here are a few tips on getting the most out of a developmental editor.

Choose the right kind of editor

The job of the (nonfiction) editor is to stand in for your eventual reader, and to detect problems that interfere with your book’s ability to connect with and communicate ideas to that reader.

That means the editor should have two significant qualifications.

First, they should be an expert on books, and in particular the type of book you’re writing. If it’s a business book, you want someone who’s written and edited business books. If it’s a memoir, find someone who knows about memoirs. If it’s history, get a history book editor. All decent editors know how to diagnose and correct problems with language, such as passive voice and word repetition, but an editor who is familiar with your genre will know how to find and fix problems in, say, the way you give advice in a business book.

Second, they should be somewhat familiar with your content. If you’re writing a book about technology, you want someone who has edited technology content. If you’re writing about gardening, you want someone who knows about plants.

Even so, you probably do not want a deep expert in your content area. Such an editor would suffer from “the curse of knowledge” — that is, the editor would know so much about a topic that they would be unable to take on the role of a naive reader. If you’re using terms that would be unfamiliar to your typical readers, the editor ought to be able to catch that issue and call it out.

As an editor, I can “fake it” as an expert in AI, customer experience, innovation, or marketing — because I’ve edited content in all those areas. That’s quite sufficient for an editing job. An actual marketing or AI expert is less likely to also be an expert in books and language, and would likely be a weaker choice for a job like this.

Describe the publishing context

Here are some things your editor will want to know.

- Who is the target audience?

- What is the goal of the book for you as an author (for example, generate consulting, generate speaking engagements, improve your reputation, or be useful for your company to hand out at events)?

- What is the publishing model? Traditional publishing, hybrid publishing, or self-publishing?

- Is this a first draft or a final draft?

- Do you (or your publisher) think it is too long or too short? What’s your target word count?

- How open are you to significant changes, such as rearranging chapters and parts of chapters?

- Is there room to refine the main idea, or is that completely settled?

- What’s the deadline?

Submit a complete, imperfect manuscript

An editor like me can add the most value by seeing the whole manuscript at once. This allows me to see problems that occur because of, for example, inconsistencies between chapters, chapter organization, or repetition of material across chapters.

I’d much prefer a whole manuscript with known problems (say, sentence fragments, or weaknesses in storytelling) to a partial manuscript that’s close to perfect. I can find and fix the problems, but I can do little more than imagine what’s in the chapters I don’t have yet.

If you can’t deliver the whole manuscript at once, an alternative is to deliver it in two or three big chunks, or with a chapter missing.

I can also edit one chapter at a time. But work like that is as much coaching as editing. I can help you see how to write better, which will help with later chapters, but once the manuscript is finally complete, it will require an additional read that looks at systematic issues across the whole thing. As you might imagine, coaching by chapter along with an additional full-manuscript edit ends up costing a lot more.

The other problem with coaching/editing a chapter at a time is it tends to go slowly. I once had an author who would deliver a chapter a week — that was almost like editing the whole manuscript at once. But I’ve had other clients that go months between chapters. This makes it hard for me to retain the context of what I read so many months ago.

Advise me what you’re worried about

Don’t hide the flaws that you know are there. I need to know what they are so I can help you fix them.

Is it wordy? Poorly organized? Too technical? Is the storytelling weak? Are there words you think you use too much? Are you concerned about the strength of the idea? Is the title inadequate?

If you hide these things from me and I don’t concentrate on them, the manuscript will be poorer for it. We’ll all be better off if you tell me what you’re worried about so I can help you fix it.

Submit a clean manuscript

This really ought to go without saying, but you have to submit a manuscript in electronic format. Most editors are happy to deal with Microsoft Word or Google Docs. If your manuscript is in a specialized format like LaTeX, you’ll be limiting your editors to people who understand that system.

Your manuscript can have some comments in it (for example, “I’m not sure this story makes the point clear, what do you think?”), but shouldn’t be crowded with them. And it ought not to include extensive back-and-forth between yourself and others involved in the project, such as coauthors and reviewers. I’m there to edit a manuscript, not resolve disputes among reviewers — I don’t know enough (and don’t really care) about your internal politics to do that. Remember, the reader won’t see those squabbles, so I don’t need to, either.

Even if it’s got leftover edits from a previous draft review, I don’t want to see them. Get rid of all the redline markup. If there is any markup visible, the first thing I will do is accept all the previous edits and work from a clean copy.

One more thing. If you do submit in Google Docs (or a real-time collaborative version of Microsoft Word), I’m going to make my own local copy. I’d rather not have you watching me make edits in real time. I might change my mind about something based on what I read later in the manuscript. I don’t like to work in a fishbowl with the author looking over my shoulder; I’ll let you know when I’m done.

Learn to manage markup and styles

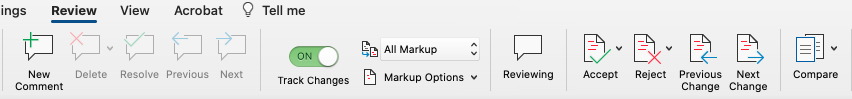

Your editor will likely be submitting feedback in Microsoft Word markup (also known as redlines — where all changes are marked in another color), or in suggesting mode in Google Docs, which works in a similar way. In addition to the redline markup, you’ll see comments.

It is your responsibility to address all those edits. Accepting all the edits is unwise — you should review each one. (Editors make mistakes, too, or may be making edits that twist your desired meaning.) And take a look at the comments and address them as well.

Whoever is downstream from this process — a publisher or even the same editor on a later draft — likely doesn’t want to see the markup. It’s your job as an author to deal with it.

Both Word and Google Docs have a Styles feature. It allows you to, for example, designate which text is a heading, which is a bullet, and which is a figure caption. It can also takes care of putting space between paragraphs. Take a moment to learn how this works. It helps your editor to identify the structure of your manuscript — such as which heads are A-heads or B-heads. Just putting headings in bold and separating paragraphs with multiple line breaks makes it harder for the editor to perceive that structure.

Be realistic about deadlines

I like to work fast. That means, unless I’m working on another book already, I can probably turn around a 50,000 word book in two or three weeks.

Don’t ask an editor to do it in a week. The results will be poor, and you’ll pay extra.

Most editors don’t work at my speed. Don’t be surprised if an editor needs a month to review a whole book.

Don’t confuse developmental editors with copy editors

The job of developmental editors is to make your manuscript better. The job of copy editors (or in the UK, “subeditors”), is to find every mistake in spelling, grammar, and formatting and show you how to fix it.

While a good developmental editor will find many grammatical problems, it’s not their job to find every single one. You’ll be introducing more when you fix the problems the developmental editor found, in any case.

And conversely, at the end of the process, don’t expect the copy editor to fix substantive problems. Copy editors are there to perfect a manuscript that’s already nearly done, not to deal with work in progress.

Don’t waste editors’ time — or your own

You don’t have to do any of this. You could just lob an incomplete manuscript full of comments and redlines to a randomly selected editor, tell the editor nothing, and fail to mention anything that you think might be wrong.

The editor will then try mightily to make sense of what they’re reading and help you. Unless they’re clairvoyant, they’ll make mistakes because of the lack of context. And the result will be an edit that could be a lot better.

That would be a shame, because if you’d put in just a little effort ahead of time, the results could be much more useful. That would lead to a far better next draft, and a far better book. So next time you need to hire an editor, prepare to meet them halfway. In the end, your readers will benefit.