Why you (probably) need a book agent

You want to publish a book. Do you need a book agent?

Yeah. You probably do.

Since there’s so much confusion about agent and publishers, here’s an FAQ for you, answering the questions I hear most often from authors.

How do agents get paid?

To understand when an agent makes sense and what they do for you, start with how they get paid. A reputable agent takes 15% of any payments you get from publishers, including advances paid up front and additional royalties. (Any agent that doesn’t operate this way — asks for money up front, for example — is not reputable, and you shouldn’t work with them.)

This is a great arrangement. For one thing, because their money comes out of your advance and royalties, you don’t need to open your wallet. Second, if you want to get the maximum possible payment from a publisher, the agent’s interests and yours are perfectly aligned — the more money they can get for you, the more they can get for themselves.

In most cases, the contract says that publisher pays the agent and the agent pays you. That might scare you, but reputable agents want to keep a sterling reputation for being author advocates, so they typically pay rapidly after the publisher pays them.

Should I use an agent if I’m self-publishing or working with a hybrid publisher?

No. An agent will only be interested in working with you if the publisher pays you, which is part of a traditional publishing deal. In hybrid and self-publishing models you don’t get paid an advance, so the the agent won’t work with you.

(In theory, an agent could work for a percentage of the per-book royalty payments in these models, but that’s not a very good deal for the agent.)

An agent talked to me and said they liked my book idea. Is that a good sign?

No. That’s pretty close to worthless.

Remember the agent’s motivation. If you don’t have a proposal yet and are working on one, they’d like to encourage you until they see the proposal. It costs them nothing to be friendly and encouraging, and it makes you want to work with them in the future. So unless you’re a complete loser with a stupid idea, they’re going to be nice.

It’s not a bad sign, but it’s like encouragement from your mom: it makes you feel good, but doesn’t accurately reflect how realistic your expectations are.

So how do I get an agent’s actual read on my idea?

Write a proposal. Then the agent will respond in one of three ways.

They may reject it. If that happens, you should at least ask why they won’t handle it so you know what to fix.

They may accept it with requests for minor revisions. Make them.

Or they may ask you to fix specific problems, for example, your marketing section, your title, or your sample chapter. That’s work, but remember, the agent won’t spend time on your book unless they think they can sell it. They’re asking for those changes because that’s what’s needed to sell the book.

You can always try to go get a different agent if the chemistry seems off. But whatever the flaws are that the first agent pointed out, take them seriously. If one agents finds a weakness in your proposal, others are likely to have a similar reaction.

Can I work with more than one agent?

No. This will confuse publishers, make the agents hopping mad, and destroy any chance you have of getting this book published or any other.

You can pitch multiple agents, but you should be honest about that with the agents you’re pitching. Once you pick one, tell the others you’ve done so.

You’re much better off working with one at a time.

The exception is if you are selling multiple types of rights: you might have a book agent and an agent representing your television and movie rights, for example.

And you can go to a different agent on a second or third book from the one you used for the first. But never use multiple agents to pitch the same book to publishers at the same time.

Do I need an agent if I already have a relationship with a publisher?

You can certainly make a deal directly with a publisher if you already know one. For example, if you’re doing a second book, it’s pretty easy to go back to the publisher of the first book and try to get a deal for that — no agent required, no 15% agent fee.

But the publisher is going to pay you more if they believe you’re going to be pitching other publishers, too. You might miss something in the contract that an agent would catch. They might try to string you along for months without a decision. These are all issues that an agent could help with. (And, incidentally, they’re all experiences I’ve actually had with publishers when I didn’t use an agent.)

What actually happens during the pitching process?

This is where the agent’s value becomes most apparent.

The agent will email a package including your proposal to a bunch of publishers, typically at least five.

The agent knows who is buying and what the editors’ tendencies are. They know exactly who to send the book to and what to say to them. That information is constantly changing, and the agent knows all those acquisitions editors and what they’ve been doing lately. That’s knowledge you don’t have and couldn’t easily find out.

When the proposal shows up in the acquisitions editor’s inbox, that editor is going to give it a good read and discuss it with their colleagues. That happens because it came from the agent, which means it’s at least worth paying attention to. If you send it without an agent, they’re a lot less likely to consider it.

The agent will likely send you around to visit some of the publishers. I was shocked to learn that the point of this is not for you, the author to impress the publishers. It’s for the publishers to impress you. In any case, it helps everybody to get to know each other before the bidding starts.

If more than one offer comes in, the agent manages the process. In one of my books, the agent conducted an auction in real-time via email with the publishers (which was very exciting). The same agency repped a different book of mine by asking each publisher to submit their one best offer. I was confused about the two different models, until she explained the reasoning: the first book attracted only business publishers, competing as peers; the other book attracted more diverse publishers whose offers ended up varying by a factor of ten. I was very pleased to have that expertise on tap.

On multiple occasions, the agent I’ve worked with has gone back once we were ready to accept an offer and sweet-talked another $10K or so of advance out of the publisher before we signed the deal. That’s not something you can probably do on your own.

By the way, there’s no requirement that you take the highest offer. You might like one publisher a lot more than another. The agent, of course, wants you to take the highest offer because they get paid more that way, but in the end you need to sign the deal, and they’ll go along if you want to pick an offer that’s somewhat lower because you liked that publisher better.

On my first book, counting up advances, foreign rights fees, and royalties over the years, the agent ended up pocketing about $75,000 of the publisher’s money that otherwise would have gone to me. And I’m delighted with that. Why? Because my 85% of the deal would never have happened without the agent’s knowing who to pitch and when. (And that agent always takes my calls now — unsurprisingly enough.)

Does the agent help after the deal is closed?

Yes. A lot.

The offers are basically handshake deals that include an advance and royalty percentages. But that’s not a full contract. Once the handshake deal is in place, contract proposals will go back and forth.

At that point you’re negotiating things like foreign rights sales and percentages, audio rights, ebook royalty rates, dramatic rights, rights of first refusal on subsequent books, paperback royalty rates, sales in foreign markets, pricing on author copies, and many more details. The agent knows which of these are negotiable (for example, foreign rights) and which are not (for example, the basic royalty rate). I’ve seen an agent propose changes in nearly all of these and the publisher just agree to all the changes.

My agency also includes lawyers, which means they know in detail how to read the language of publishing contracts. They’ve also seen dozens of contracts from each publisher, so they know the quirks in each publisher’s contracts and legal departments. But even when they are not lawyers, agents have seen hundreds of book contracts and know what to look for and where the red flags are.

The agent is also your advocate. It can take months to negotiate the contract, and you’re not getting your advance until that’s done. The agent can pester the publisher’s legal people and acquisitions editors far more effectively than you can. Why? Because if the agent starts to believe a particular publisher is a pain-in-the-ass, that publisher’s reputation will suffer. Agents talk, and they work collectively with an awful lot of authors.

The agent can also answer your questions during the process (“The publisher is asking for x, is that typical?”) and even after the book is published. For example, if a royalty statement is late or looks wrong, the agent is in a much better position to fix that problem than you are. Since the agent has gotten paid out of your advance, they’re able to put in the time to maintain the relationship and provide service to you. That’s part of the agent’s effort to get you to re-up with them on the next book.

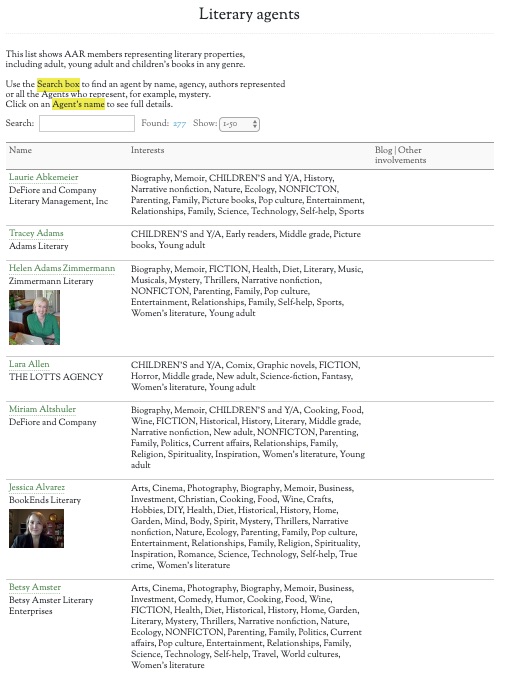

So how do I find an agent?

For unknown authors, this is a problem.

Authors pitching agents without an introduction face long odds. One agent told me, out of hundreds of unsolicited pitches she gets in a year, she might pick up one or two.

But she also told me she picks up a couple of pitches a month from people who come through a referral through someone she knows. She still turns most of those down, but the odds are much better.

What does this mean for you? Well, I hope you have a friend who is an author or editor or works in publishing. Talk to them. They can refer you to an agent and the agent will consider you. (And remember what I said earlier — the agent may be encouraging, but until they’ve seen your proposal, their encouragement isn’t worth much.)

This is one reason of many why authors should network as extensively as possible — and not just for moral support. The more people you know and trust, the more likely you’ll end up friends with someone who can refer you to an agent.

When I work with authors on ideas and proposals, I’m happy to refer them to my agent, and the agent is happy to review their proposals. (Some still get turned down, to be sure.)

If working with the agent seems like a whole lot of trouble, you can always consider self-publishing or hybrid publishing. But if you’re pitching traditional publishers, you’re better off with an agent on your side.

Out of curiosity, how much do agents help with sales once the book has been published? Are they helping to book speaking engagements/signings, etc? Or does that move into the realm of publicist?

They don’t help with book sales. That’s pretty much the author’s job.

And they don’t help with speaking. That’s the speaker’s bureau or possibly a publicist.

If I sent you my self-published book and you loved it, would you refer me to an agent; or would you tell me that, as an indie, I am a persona non grata to the traditional publishing world?

Traditional publishers have no problem with people who self published. They’ll publish your next book if the proposal looks promising.

If your self pub book is selling great, they could be interested in republishing it. I’ve seen this happen at least twice. If it’s selling poorly they’re not interested in republishing it – you’ve proven there is no market.

If you want help pitching your next book, bring it on.