“Why They Can’t Write”: John Warner’s brilliant analysis of the failure of teaching

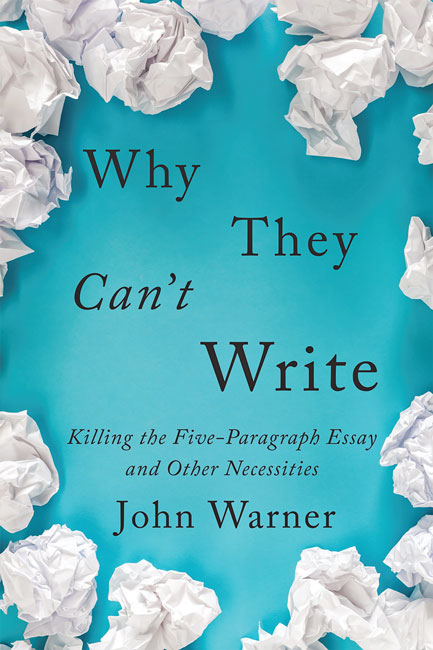

Anyone who has had any interaction with education these days — as a student, a teacher, or a parent — is likely to have the feeling that something fundamental is awry. John Warner’s has some good ideas on what’s wrong and how to fix it. His book Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities is as clear, unequivocal, and arresting as a slap in the face. Everyone should read it.

John Warner has taught writing at four colleges and contributes to the Chicago Tribune and Inside Higher Education. Based on that, you’d expect this book to be an analysis of the teaching and learning of the skill of writing. But the problems with writing are emblematic of the problems of education in general — and this book doesn’t stop in the English Composition department.

The tragedy of the five-paragraph essay and standardized writing tests

Start with public school. Simply put, the teaching of writing in high school does not teach students how to write.

Warner starts with the analogy of training wheels on a bicycle. You bike with the training wheels and you imagine that you are learning to ride a bike — but instead, free of the actual need to balance, you are learning only to propel the bicycle forward. Take the training wheels off, and you’re going to fall, whether you’re three years old or 13. All the training wheels do is fool you and delay your learning.

It is the same with the “writing” tasks students undertake in school. The execrable exercise that is the five-paragraph essay is a great example. Students must fill in the blanks in a standardized format that rewards typing, not thinking. But the five-paragraph essay is easy to teach and, more importantly, easy to grade. This allows teachers to be, at least in a cursory examination, more efficient — that is, to teach a greater number of students in the same time period. Thus “education” happens — and as Warner and every other college professor has experienced, the students arrive at college with no idea how to conceive ideas, how to do research, how to organize ideas, how to thread them together, how to satisfy the needs of an audience, and how to delight with the tools of language.

Similarly, Warner decries the little reading and writing exercises that we use to evaluate student writers’ skill with standardized tests. Reading a passage and answering questions about it rewards “close reading” but not the generation of ideas. The essay portion of standardized tests — started in 2005, and abandoned in 2014 — was a test of whether students could generate a bunch of words that a grader could grade quickly. As Warner writes:

The original version of the SAT essay was a timed, handwritten exam with a prompt closed in terms of topic but entirely open in terms of content; furthermore, access to outside sources and research was forbidden, making for a set of conditions under which precisely zero writers work in the real world. . . . The resulting writing was scored in no more than three minutes by anonymous graders hired as temporary workers who had to adhere to production quotas. Imagine Lucy and Ethel at the chocolate factory, only with students’ blue books instead of bonbons. . . .

In fact, to do well on the essay-writing portion of the SAT, Les Perelman, former director of MIT’s Writing Across the Curriculum program and an expert in designing and evaluating writing assessments, had some advice: “Just make stuff up.”

“It doesn’t matter if [what you write] is true or not,” Perelman said. “In fact, trying to be true will hold you back.”

The education hype cycle

Many of us are familiar with Gartner’s hype cycle, an insightful deconstruction of how the tech and business media adopts, hypes, and then becomes disillusioned with new technologies, almost independent of their actual merit.

But until Warner pointed it out, I hadn’t realized the same hype cycle applies in education. Only the difference is, instead of companies chasing illusory gains from blockchain or virtual reality, we recreate the entire educational system around the latest educational theory and then subject a whole generation to it.

In teaching, these fads have included “self-control” (along the lines of the now debunked “marshmallow test”), standardized tests and No Child Left Behind, Common Core, “grit,” and especially, AI-driven computerized and personalized learning that demoralizes children — but frees up teachers from the drudgery of actually teaching.

Warner’s deconstruction the education hype cycle is insightful and brutally honest:

1. Research uncovers an interesting finding that seems correlated to student “success.”

2. Breathless coverage trumpets a new “revolution” in learning which will unlock all students’ potential regardless of race and economic background.

3. “Success” is defined down to something quantifiable like scores on a standardized test.

4. Very quickly, all nuances surrounding the finding are quickly washed away, so any underlying causes are pushed aside in the interest of raising scores on the test that matters above all.

5. Once the key measurement has been determined, a behaviorist approach is adopted. . . [We] adopt policies that require compliance, rather than developing the underlying skill.

6. The burden of implementing the new curriculum falls entirely on teachers via administrative diktat. Nothing is removed from teachers’ responsibility to make way for this additional requirement . . . Teachers are to be held accountable for how their students perform on these new metrics while being given very little if any assistance in implementing these new programs.

7. Ultimately, nothing much seems to happen. Some students improve on these new metrics; others don’t. To the extent that they change, it’s difficult to correlate those changes to the curriculum. Basically, it’s noise.

8. Enthusiasm fades, and questions arise as to whether the latest approach is sensible. Ultimately, even supporters of the initiative climb off the bandwagon, though the lack of success is almost always blamed on “poor implementation” rather than a flawed premise.

9. A new magic bullet arrives on the scene. Return to Step 1.

The students pay

As Warner describes, this educational environment has created a demoralizing experience for everyone involved. Students are far more likely to say “I hate school,” even though they love actual learning. School is a drudge-filled chore for everyone involved, swallowing students’ motivation and resulting in an epidemic of depression and medication to fix it.

A prescription to fix how we teach writing

Warner is not just complaining about the problem. He has a solution. And it’s remarkably simple. The challenge is how to implement it.

The components of the solution are these:

- Limit the number of students per teacher, and pay the teachers a living wage.

- Assign real-world writing assignments (like a review, or a persuasive argument) and give the students the tools to analyze good examples of people who do those well. They should work inside an actual rhetorical situation with an actual intended audience.

- Focus on writing practice and rewriting based on comments from the teacher. (This means that the teacher has to have the time to generate thoughtful comments.)

- Grade based on quantity of thoughtful writing created, rather than on achieving or approaching perfection. As it turns out (at least in Warner’s classes), the more work the students put in, the more improvement they achieve, and that is worth rewarding.

The result is that students make meaningful writing, which is far more likely to make them better writers than squeezing their work into some pre-determined type of box that has so little to do with the writing they will do in the real world.

I am not doing justice to Warner’s prescription, because there is a lot more detail to it. But I found myself cheering on page after page, because it’s just so much closer to how real writers learn, whether those writers are in high school English classes, college composition classes, or writing reports or copy or emails in corporations.

How I teach writing — and maybe, how we should teach everything

Most of my experience is limited to writing workshops for corporate writers — in which they analyze the bullshit in their own company’s writing and learn to fix it — as well as editing actual writing content.

I sometimes charge $1000 or more for editing a single document. And when I do edit that document, I analyze it in detail, along with the writers’ attitudes that are causing the problems. Some writing teachers that Warner describes are getting less for teaching an entire course full of students than I get for editing a single document.

Obviously, my method does not scale. But some elements do apply. The close read of people’s writing and the thoughtful feedback makes a huge difference.

If we can give students that experience as many times as possible, they will inevitably learn to be better writers.

It’s not automated.

It’s not based on the latest fad.

It’s good old fashioned editing and improving — human-to-human teaching and learning.

I’m convinced that Warner is right about how to fix the way we teach writing.

And I’m wondering how many of these techniques could be applied to how we teach so many other things.

Let’s get off the educational hype cycle and give hands-on teaching another chance. The cure for education’s problems is teachers, not curriculum fads. I’m sure of it.

Wonderful analysis. It points to the commodification of education (and students?). Education is a human endeavor – just like learning is. At its most effective, it is deeply personal and inter-personal. Our educational system isn’t structured that way.

This is awesome! Though it doesn’t reflect the purpose and function of bicycle training wheels. I think most people don’t remember how they learned on training wheels, but their purpose is actually to let you ride while developing your sense of balance. It becomes obvious when you’re balancing on your own and need them taken off.

Once you get into the meat of the argument, it becomes more convincing. Especially when it calls for smaller class sizes and adequately paid teachers. Dependency-building teaching methods, such as the five-paragraph essay and 3 Rs fundamentals, are pretty much necessary in oversized classes.

Who knows? Maybe some of the gimmicky new methods *could* work better with decently small classes. But that means that small classes and good working conditions for teachers are the only things that could make them worth trying.

Perhaps we should treat students as if they’re apprentices. It works for trade education

Not sure I follow your reference to grit. The referenced article doesn’t seem to debunk the link between grit and academic performance. Am I misreading the article? Or misinterpreting the reason you referred to it?

The book describes the rise and fall of “grit” as a desired measure in pages 79-85. Angela Duckworth and Paul Tough, who popularized it in 2012 and 2013, have backpedaled. Duckworth resigned from the group implementing it in California, saying “I do not think we should be doing this, it is a bad idea.” And Paul Tough agrees with John Warnock that it fails to account for the inequities in the challenges children face before even arriving at the school door.

All my life, real learning occurs with me, when I get the desire. Then I go find the teachers. I just wonder how often this is the case for others.