Why (and how) to do primary research

There are two kinds of research: primary research and secondary research.

Primary research means finding new facts that have never been published before. Secondary research means finding facts that were already published.

Nonfiction books that matter almost always include primary research, because otherwise the book is just a rehash. It’s very hard to draw startling conclusions and new insights from a rehash.

How to do primary research

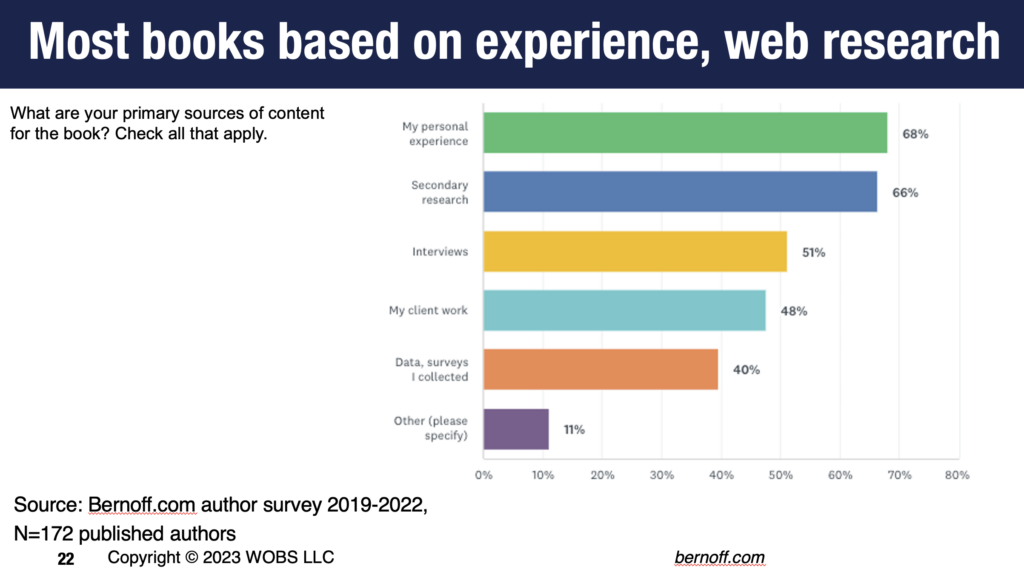

As I describe in my book, here’s what the authors in my author survey said about research. As you can see, they assemble content from a variety of sources.

Outside of actual laboratory experiments, there are three common sources of primary research.

The easiest and most common is authors’ personal experience, including work with clients. Authors can and often do write about what happened to them in their lives and their work. But unless a book is a memoir, it should not be based exclusively on personal recollections. Readers are rightfully skeptical if all they are reading about is the author’s own experience. Such recollections are inevitably subject to bias based on the assumption that everyone is like the author, or like the authors’ clients.

A second common and valuable source of insights is interviews with others. You can find case studies and conduct interviews with people you’ve worked with as well as people you’ve read about in other places. Such interviews will enliven the book and make it entertaining to read and compelling. For many books, they comprise the main source of primary research content. But case studies are, literally, “anecdotal evidence”; ultimately, a skeptical reader will wonder if they actually represent what’s going on in the space you describe.

The solidest form of evidence is data. You can either collect your own survey data or assemble and analyze data you collect from elsewhere. Even an imperfect survey (like my author survey) is more credible than a collection of stories. High quality data, like consumer surveys of thousands of people, can be expensive to collect; large-scale surveys of businesspeople or workers are even harder to conduct, and often require working with specialist survey firms that have access to such groups and analytical expertise. (If you can collaborate with an association that serves a specific group, such as human resources professionals or IT managers, those groups often conduct surveys of their membership.)

In addition to the expense and effort, the challenge with data is that it only generates a few charts and statistics. It’s hard to write a compelling book with data alone. That’s why most authors combine data, interviews, and personal experience to create a solid mix of revealing primary research.

Secondary research bolsters your credibility

Almost all compelling nonfiction books include secondary research along with primary research. If other writers have written about what you’re writing about, you really should cite their content and conclusions to put your insights in context.

Web searches are easy. But that doesn’t mean all you have to do is Google your topic and then cite whatever comes up.

Here’s what I wrote about secondary research in Build a Better Business Book:

Secondary research nuggets you can find in other sources will add significantly to the authority of what you are writing. And for the most part, secondary research is free. Your job is to identify what sources are worth quoting and cite them appropriately.

What sorts of nuggets are we talking about? Statistics. Quotes from prominent experts. Survey results from surveys conducted by large research organizations. Stories about people doing whatever your book is about, published in case studies and articles. Analogies and metaphors.

When you’re writing a book — or even considering writing one — you should constantly look out for these research nuggets. If something you read seems like a good metaphor for an argument you’re making, bookmark it. If you hear a business story or case study that applies, bookmark it. It’s the same with statistics you read or quotes that seem relevant. . . .

Of course, waiting around for good stuff to appear isn’t sufficient. You also need to go out and get it.

Here, you’re likely thinking, “Great, I already know how to use Google.” But unless you want to waste a lot of time swimming through irrelevant material — or worse yet, quote people and stats that are full of crap — Google is just the beginning of your secondary research.

Here are four warnings about secondary research that all authors must take to heart.

- Make sure sources you cite are credible. Don’t quote poorly designed studies or biased perspectives. Your job is to vet the facts you find, not just indiscriminately shovel them into your text.

- Track down original sources. Sometimes an article quotes a stat from another source, and the stat is originally from yet another source. Learn to track links back to find the original source of research. Even if a well-known author cites a statistic, that doesn’t mean the original source is necessarily credible.

- Be scrupulous about sourcing. Every fact should have a source that a reader can check. As you collect research, always keep the facts and sources together so you don’t lose track of where the facts came from. (One simple way keep track of things is to insert links to original sources in your research notes.)

- Don’t trust AI. ChatGPT will generate content without sources. And its facts are often wrong. As a research assistant, AI is far from dependable.

It’s still your story

A collection of research, primary or secondary, is not a book.

You still need to weave it all together and tell us what it means.

Research is a key ingredient. Your job as a writer is to bake it into a compelling book.