Where exactly is AI’s copyright violation?

There are now multiple lawsuits in which owners of copyrighted material — books and articles, fiction and nonfiction — claim that entities using large language models (LLMs) from Microsoft and OpenAI have violated their copyrights. But at what point in the process does the alleged copyright violation occur? Let’s examine the process of creating and deploying an LLM-based AI and see which steps would be subject to legal challenge.

As you read this, keep in mind that I’m not a lawyer or legal expert. My perspective comes from decades of experience as a media technology analyst, watching how media companies deal with new technologies including their attempts to use copyright law to protect their content from entities like Napster and YouTube. That experience informs this analysis.

This analysis addresses text-based AI, but you could easily apply it to other sources of AI content, such as graphics or code.

To start, how does an LLM work? To create one, the entity that runs it must:

- Obtain access to a large corpus of textual material.

- Ingest that text.

- Using massive collections of computing power, analyze the text and translate it into a symbolic form that is appropriate for use by the LLM.

- Respond to a prompt from a user, using that symbolic material and data about the user’s context to generate textual answers.

Let’s analyze each step from the perspective of copyright violations and examine how the AI companies might evade those pitfalls or obtain permissions to solve them.

1 Obtaining access to content

If you have to steal content, you’re potentially liable.

There’s evidence that to create ChatGPT, OpenAI gained access to a corpus called “Books3” generated from copyrighted ebooks. Books3 was created without the permission of the copyright holders. Using technological means to circumvent a copyright protection mechanism — including the one that protects Kindle ebooks — is a violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). So this is a pretty clear violation.

There is a pretty easy fix for this, of course: don’t train AIs on illegally obtained content. Operators of LLM-based AIs have likely already made this change. While they may owe damages based on past theft of content or use of stolen content, it’s unlikely that will block their future operation.

2 Ingestion of content

LLMs are “reading” the same content the rest of are reading. How is that a violation?

I’m sure you’d agree that if I read an article on a copyrighted site and then wrote about it, that’s not a copyright violation. (Half of the content of my blog fits that description.) On the other hand, if I wrote a tool that scraped the text of every article on the web site of ESPN and then posted it on my own site, that’s a pretty clear violation.

It is difficult to see how the act of ingesting content is per se a copyright violation. But owners of copyrighted content have the right to control how people use it. They manage this through their terms of service.

Consider the articles in the New York Times, which are protected by the New York Times terms of service. The terms of service includes the following text:

2.1 The contents of the [New York Times] Services, including the Site, are intended for your personal, non-commercial use. All materials . . . are protected by copyright, and owned or controlled by The New York Times Company or the party credited as the provider of the Content. . . . Non-commercial use does not include the use of Content without prior written consent from The New York Times Company in connection with: (1) the development of any software program, including, but not limited to, training a machine learning or artificial intelligence (AI) system; or (2) providing archived or cached data sets containing Content to another person or entity.

So the use of the Times’ copyrighted content violates this agreement. I cannot prove it, but I suspect the limitation on non-commercial use has been in the terms of service for a long time, predating the training of ChatGPT, even if the specifics about training an AI were added later. It’s likely that the Times can use this clause to assert that by ingesting content on the Times site, the LLMs are violating its content rights.

A similar analysis likely applies to any other copyrighted site with terms of service. If such terms are not included in a site’s terms of service, it would much harder to argue that a machine reading the site constitutes a copyright violation.

There’s an interesting parallel here to what happens when a search engine like Google ingests a site like the Times. Google does indeed ingest and index all the words on the site to fuel its search engine, and may even make a cached copy. In theory, a media site could sue Google and block it for violating the terms of service. But there is enormous benefit to a media site in allowing Google to index it, because Google can then send traffic to the site. As a result, sites don’t sue Google for accessing their content.

As things stand now, LLMs generate no such benefit — they substitute for the requested content, rather than generating traffic to it.

The quantity of content ingested makes a difference here. For a single small piece of pirated content, it would difficult to prove significant damages. But LLMs are designed to ingest content in massive quantities, without regard to copyright, and the result of that action significantly threatens news organizations’ livelihood, potentially cause for compensation for large amounts of financial damage. When the courts ruled against Napster, they declared such mass copyright violations to be illegal.

One solution to this problem would be for LLMs to pay licensing fees to content owners. In theory this would solve the problem. In practice, making agreements with millions of content owners would be impractical. A potential solution may involve innovation in making mass licensing tools, and in using web code to mark sites as inaccessible to LLMs.

3 Analyzing and processing the text

If you’ve obtained permission to ingest the text, you’ve likely obtained permission to process it using technological means.

This is the “secret sauce” of any LLM-based AI. If there is a copyright violation, it’s unlikely to happen in this stage.

4 Responding to prompts

Is there a potential violation in the output of AI products?

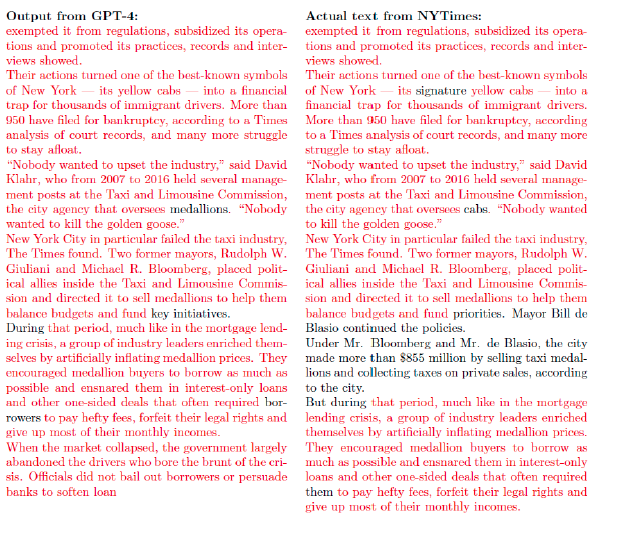

If they cough up material substantially similar to the what they ingested, there is. In its lawsuit, the Times included this example from ChatGPT.

This is as clear a violation as if ChatGPT posted a web site made up of copies of the Times’ content.

However, ChatGPT creator OpenAI claims that this output is a bug in the program that they’ll be fixing.

If LLM-based AIs continue to output content so close to what they ingested, they’re obviously liable. But in my opinion, this behavior is unlikely to continue. Future versions of these AIs will be designed to avoid outputting copyrighted content verbatim.

Is the solution technological or legal?

In an ideal world, lawmakers or regulators would create an equitable solution for compensating copyright holders for the use of their content by LLMs. The likelihood of an agreement on this any time soon is low, because it is a contentious and rapidly-changing issue.

The actual solution will emerge from the disposition of the lawsuits. The courts will determine what is actionable. This will set the stage for owners of large collections of copyrighted material, such as newspapers, media companies, and publishers, to negotiate terms for the use of such content. Such terms will also have to address the rights of authors who are paid royalties. As happened with ebooks, it may take decades for authors’ contracts to appropriately address such issues, and they’ll be subject to negotiation in each individual publishing contract.

In the next three years, look for web sites to implement flags indicating whether their content can or cannot be ingested for AI tools, much as they now do for search engines that crawl the Web.

Unlike previous copyright ripoffs such as Napster, AI-based tools are becoming increasingly useful, even essential. It’s in everyone’s economic best interest to create a solution to this problem. Because of the speed with which the technology is evolving, I’m betting on a technical and financial resolution, not a legal or legislative one.

What do you think? Are there other places where AI violates copyright? How will this all pan out?

There’s a new AI-based search engine / chatbot, called Perplexity.AI, that not only generates answers to your questions, but also includes links to where it sourced its answer.

Maybe, based on what you said about Google, this is no longer copyright violation because the original source material is being referenced?

I said sites accept Google because it drives traffic. That doesn’t mean they want the same deal with an AI company.