When is a killing justified by self-defense? My survey reveals that we’re not that sure.

We all think we know what “self-defense” means as a justification for killing someone. But based on my survey of 186 people, our perspectives are nowhere near consistent.

Here’s a recap of the data you’re about to read about.

Using my blog, my Twitter account, and my Facebook page, I encouraged people to take a short survey about self-defense scenarios and determine whether, in each one, they would vote guilty of murder, not guilty, or unable to decide. I presented respondents with 20 scenarios that took place in people’s houses, neighborhoods, and on the street, with various degrees of perceived and actual threats.

This is not a random sample and it would be inappropriate to project results from this survey to the general population. However, given that my readership is likely to be more homogenous than the general population, I suspect that the high degree of disagreement on many of these questions would also extend to a random sample of American adults. In other words, I’m pretty sure that, in many cases, we don’t agree on what constitutes self-defense as a reason for killing.

This is relevant right now, as two highly publicized trials just concluded in which self-defense was at issue. Kyle Rittenhouse, the 18-year old who travelled to Kenosha, Wisconsin and shot three protestors, was acquitted on self-defense grounds. But Travis McMichael, Gregory McMichael, and William Bryan Jr, who cornered Ahmaud Aubery while he was jogging through their neighborhood in Brunswick, Georgia, were convicted of the murder despite making self-defense arguments.

I received 223 responses. I analyzed only the 188 respondents who had completed all questions in the surveys. All respondents stated their age as 18 or older. Of the 188 complete responses, 151, or 80%, were citizens of the US. Because of the differences in the application of the law, I analyzed the responses of US citizens separately from those from other countries.

Of the 151 US citizen responses, 139, or 92%, had no formal legal training, and 12 were lawyers, law students, law enforcement, or other people with legal training. As I describe, in some cases, those with legal training had quite different opinions from ordinary citizens.

Many of you told me you were uncomfortable making these choices

Many of my survey respondents said these scenarios made them think very hard about these challenging issues. Some comments:

The topic made me think of the many situations happening daily. When stressed, we do not always make the right decision.

This was interesting. It also makes me hope I am NEVER on a jury where something like one of these scenarios needs to be decided.

Very thought provoking. Glad to participate

My scenarios were intentionally brief. I also stated at the start of the survey that all the defendants had the intent to kill — so the appropriate charge was murder, rather than manslaughter. Admittedly, these brief scenarios leave room for interpretation. But it was also clear that many people were seeking a way not to have to make a decision.

Some scenarios should have had a choice of a lesser charge than murder.

“Guilty of Murder” is such a strong term versus “Not-Guilty”. In some of these circumstances, something in between is clearly warranted. In other circumstances, the descriptions in this survey are so void of necessary details as to not allow one to view them in an objective way.

For those [marked] “I can’t decide”, I wanted more information before I felt comfortable rendering a verdict. I wasn’t leaning one or the other way, just wanted more information to work with. Thank you for making me think most days each week!

None of them conveyed enough information to decide if there was a murder or not. For each, there would have been case-specific extenuating circumstances and more information to consider. In addition, the legal definition of murder and self-defence varies from state to state.

Killing in self defense is not murder, except perhaps in cases where the victim’s threat or weapon used cannot be reasonably used to end a life. Apart from that, killing in self defense is not murder.

It’s police duty. In most of the cases above, the best solution is not to open the door and call 911.

Fascinating because there’s a tension between the “logical” response and how someone acting in the heat of the moment might actually behave.

Many/most of the situation are grey areas where my opinion would depend on the exact circumstances.

Respondents outside the US found the questions horrifying because of their perception of the much higher degree of gun violence in the US.

As I’m in the UK and we have among the strictest gun laws in the world, I found each scenario frankly terrifying

As a Canadian, I am noticing how I’m reacting to the presence of guns in the scenarios. If the law is about a legitimate feeling of threat, then the presence of a gun seems to make so many scenarios pass the test. Even for Rittenhouse, the fear that someone would disarm him and beat him seems realistic. I find it so sad that U.S. laws make the Rittenhouse verdict lawful.

I’m not American. Do you feel you need to take this into account for such a survey given that many (most?) countries not called the USA do not have laws like stand your ground?

America – The division and vitriol in public discourse is sadly, brutally intolerant and unreflective at least to outside eyes. These scenarios are often what people believe or perceive to be true – which have confirmation bias, which is dangerous if we are confirming intolerant perceptions and acting on them out of fear. Ready, fire, aim. I love America it’s welcomed so many of my relatives, but rampant individualism has its consequences for community, tolerance and respect. Reflection needed, rather than posturing, and pontificating on positions. Just an opinion

I’m an Australian, so I’ve answered these questions from an Australian perspective, where to justify taking a life in self defence your belief that you are likely to suffer death or serious injury must be both genuine and reasonable.

Analyzing the “torches at the door” scenarios

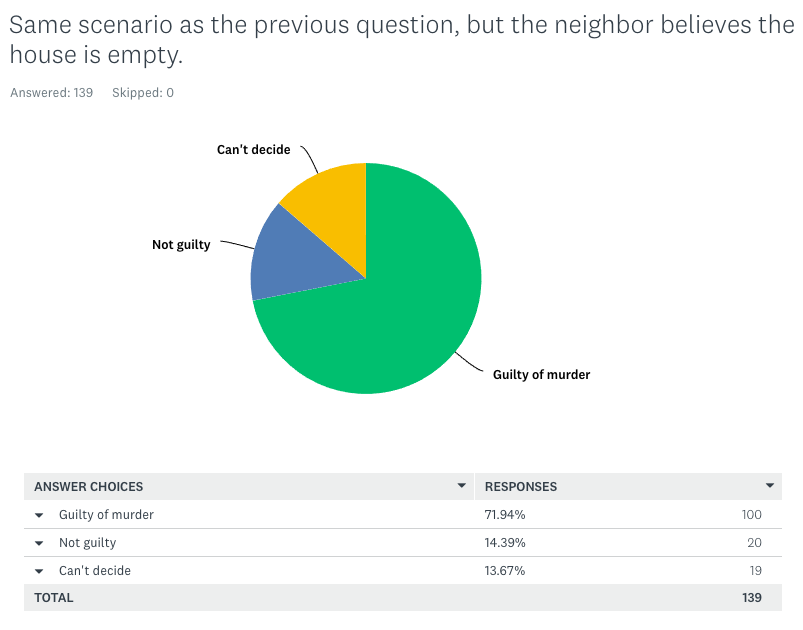

I presented five scenarios in which an individual or a group appears at the door ready to do violence. In different questions I varied whether or not the person at the door was armed, and whether it was the defendant’s house or a neighbor’s house.

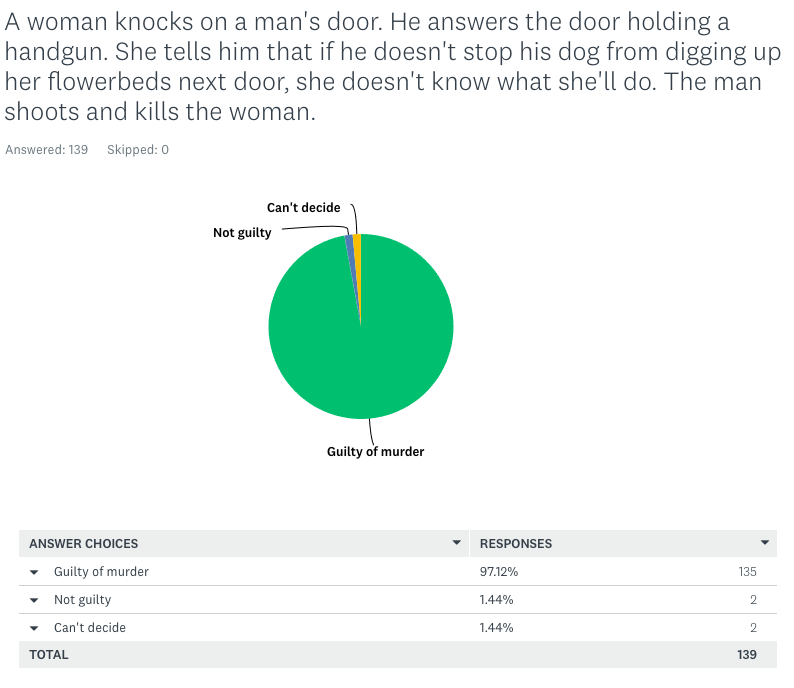

Nearly all of the respondents agreed that you couldn’t just shoot somebody who comes to the door angry. Of 139 US respondents without legal training, 135, or 97%, agreed that the defendant in that situation was guilty. All 12 of the Americans with legal training also agreed this defendant was guilty.

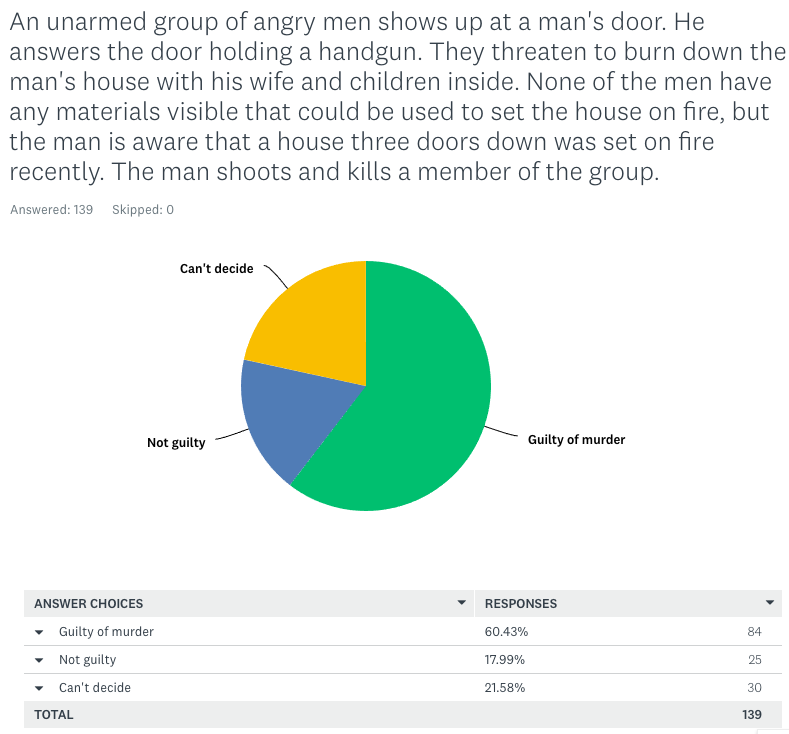

When the group at the door consists of unarmed men making threats, 60% of American respondents without legal training would still convict the defendant of murder, but 22% can’t decide and 18% would accept a self-defense argument. (Of the 12 respondents with legal training, only 4 would convict in this case.)

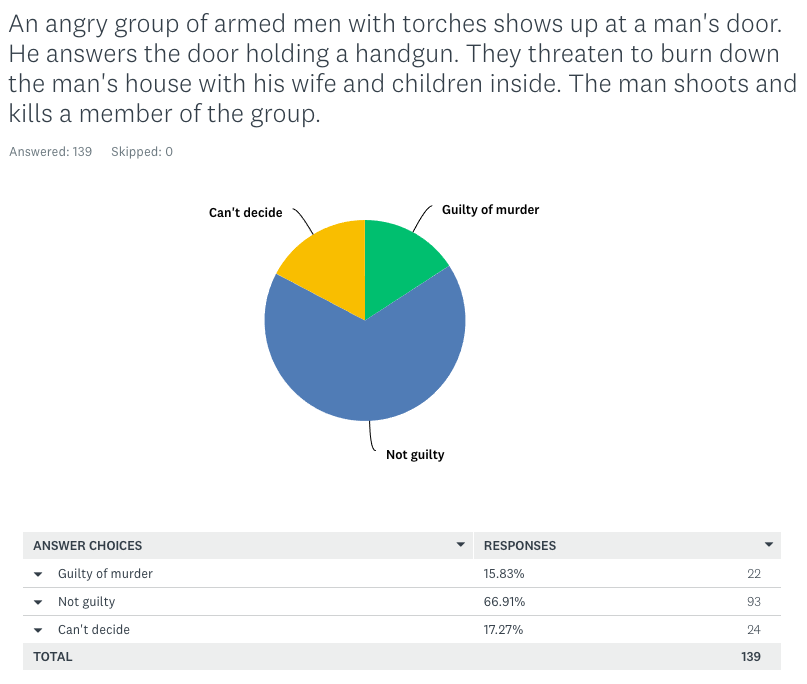

Even if the men at the door have torches and are threatening to burn the house down, some of respondents would not accept a self-defense argument. In this case, two-thirds of the respondents vote to convict, and the remainder are split between voting guilty and undecided. This result is unchanged whether or not the respondents have legal training. Among the 37 respondents from outside the US, only one would find this shooter guilty, while 27, or 73%, would find him not guilty.

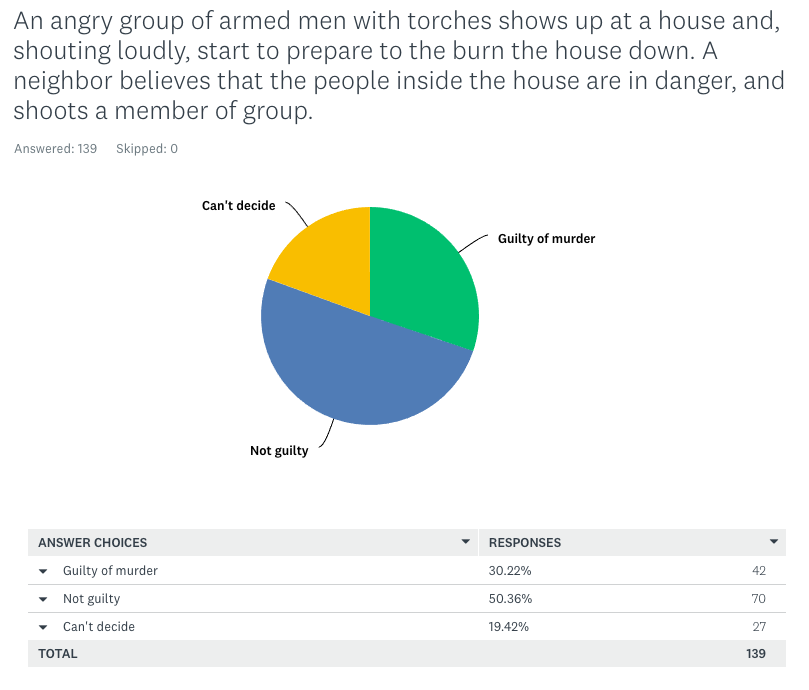

Is it justified to shoot to protect your neighbors? Half of you think it is; you would vote to convict a man who shoots people attacking his neighbor’s house. The same proportion applies to votes from both US citizens and those from outside the country. But this scenario is apparently at odds with the law, since all of the 12 people with legal training would vote guilty in this scenario.

Things change if the defendant is defending only a neighbor’s property. Now 72% of US respondents without legal training would find the shooter guilty, and only 14% not guilty. Answers from respondents outside the US were similar.

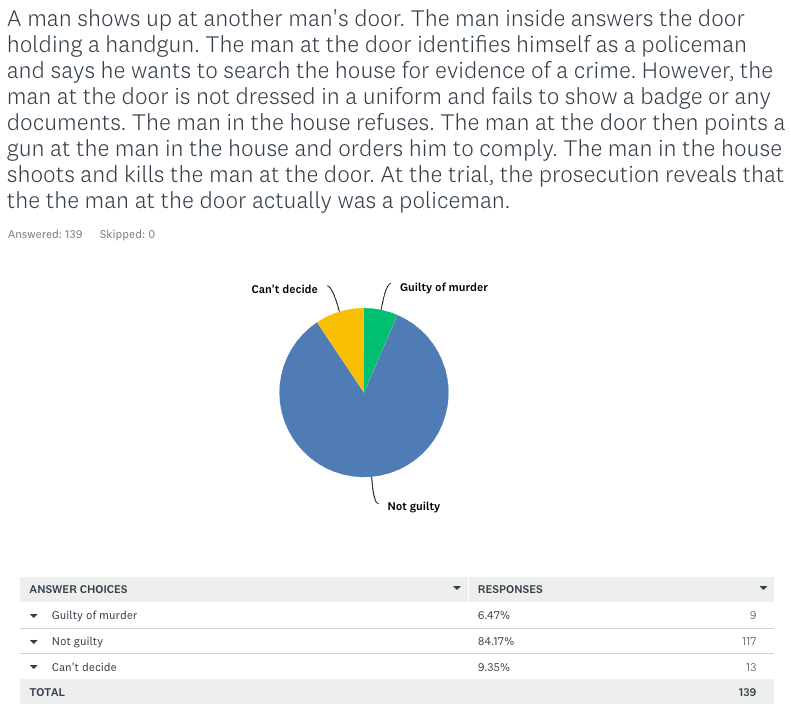

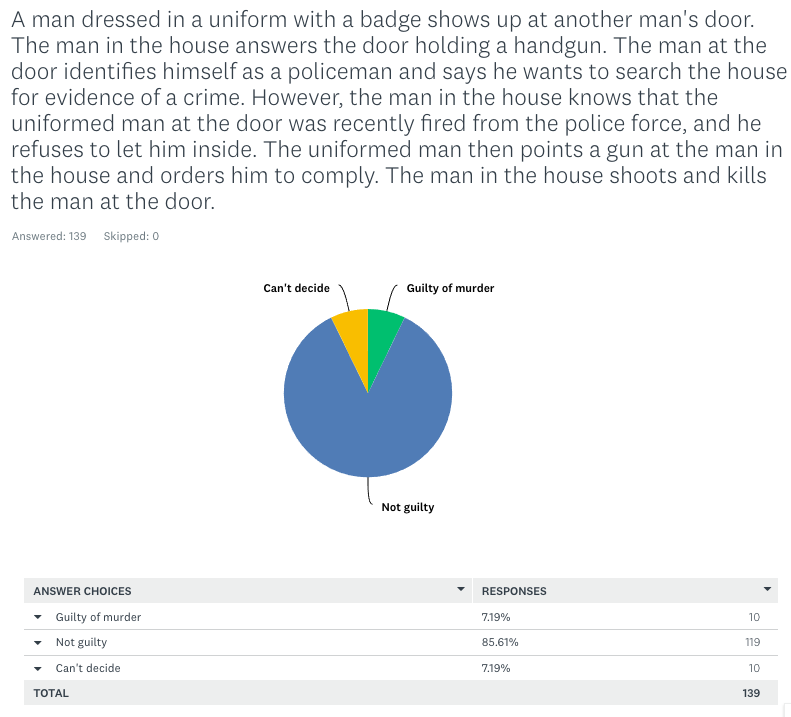

Can you shoot someone who says he is a policeman?

The other set of “defend your home” scenarios concerned people who say they are police. Here’s one:

The overwhelming majority of US respondents without legal training — 84% — agree that you can defend yourself against an armed man who says he is a policeman, if he has no proof or documentation of his role in law enforcement. Among those with legal training, nearly all agree that such a shooting is justified. Results are similar from those outside the US, but 6 out of 37 — 16% — would find this defendant guilty.

I was pleased to see that the results were similar regardless of whether the person a the door was, or was not, actually a policeman. Without identification, of course, the person defending themselves has no way of knowing the assailant’s true identity.

Opinions are also similar in the final policeman-at-the door scenario, where the defendant knows the assailant is only pretending to be a policeman.

What I learned from these survey questions

What I find most fascinating here are the questions in the murky middle, like the question about shooting someone setting fire to the neighbor’s house. It’s clear that in some cases, our ideas about safety, killing, and self-defense are not consistent. If you have a weapon in your hand, your idea of whether you are actually under threat may differ from what jurors will say. And that’s a prescription for a lot of confusion in a deadly situation.

I’ll continue the analysis with the battered spouse and attack-on-the-street scenarios tomorrow.

This is great stuff, Josh. A bit scary to contemplate, and very serious. Thank you.

Agreed. Very interesting. I’m a bit horrified by the responses from the Americans with legal training on scenario 2.

“An unarmed group of angry men shows up at a man’s door. He answers the door holding a handgun. They threaten to burn down the man’s house with his wife and children inside. None of the men have any materials visible that could be used to set the house on fire, but the man is aware that a house three doors down was set on fire recently. The man shoots and kills a member of the group.”

8/12 with legal training say this shooter is not guilty? Wow. With 60% of the rest of the American responses taking the opposite view, I think this perfectly summarizes the disconnect between what we feel in our guts is justified, and what is legal.

This set of Americans in this survey with legal training is a small sample. It includes 2 lawyers, 3 present or former law students, 2 paralegals, 1 in law enforcement, and 6 with unspecified “other legal training.” So I’d be careful about reading too much into the views of this group.

Fair enough. Thanks again for conducting this survey and sharing your analysis!