More attitudes from the self-defense survey: battered spouses, street crime, and riots

This is a continuation of my analysis of 186 responses to my survey on self-defense. Let’s take a look at the rest of the scenarios, which apply to battered spouses, crime on the street, and shootings in riots.

When is it okay to shoot your spouse?

I presented people with three battered spouse scenarios.

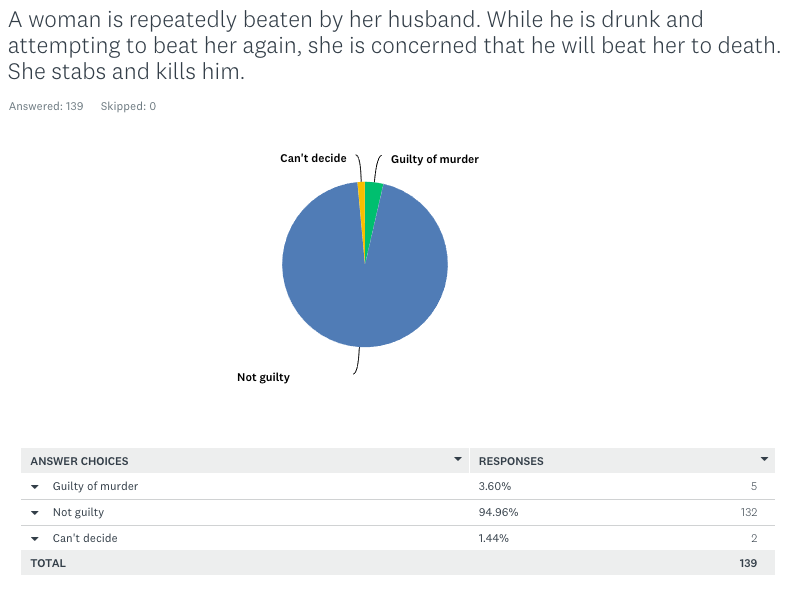

Can you shoot your husband if he repeatedly threatens your life? Among Americans without legal training, 95% say yes. (A few of those with legal training said “Can’t decide,” presumably needing more evidence, but 9 out of 12 voted “Not Guilty”) Five out of 151 US respondents said a woman who shoots a threatening husband isa guilty of murder. Those answers surprised me, as I’d say this is the classic definition of self-defense. Among the 37 answers from outside the US, 80% would find the wife not guilty, and 14% would find her guilty.

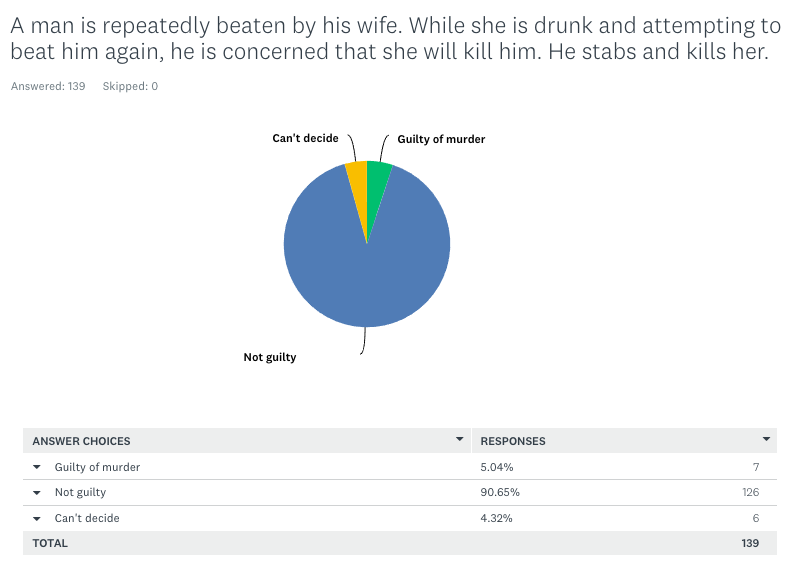

When I flipped the scenario to a battered husband, the results were nearly, but not quite, the same. Six out of 139 US respondents without legal training switched their votes away from “Not guilty.” Who are these people who doubt a woman could threaten a man sufficiently to make him credibly fear for his life? They’re all white and over 35, and three are women. If you’re a man whose wife is threatening you and you defend yourself with deadly force, you’d better hope one of these people isn’t on your jury.

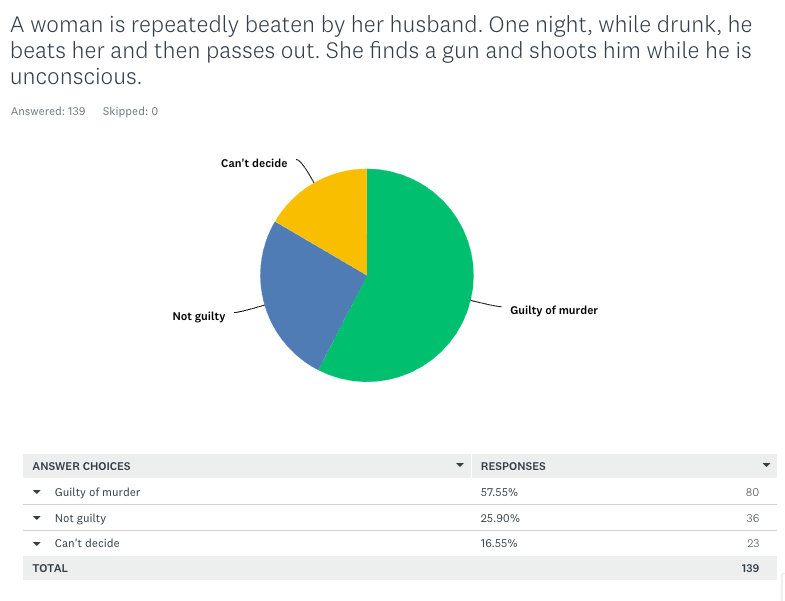

Some decisions here are very challenging. Can a repeatedly beaten woman shoot a husband who is unconscious? Obviously, in this situation, there is no immediate threat, but the woman is still in fear of her life. Among Americans without legal training, 58% would find the wife guilty, but almost half would find her innocent or couldn’t decide. Surprisingly, the results were almost the same among those with legal training, which tells me that this situation is murky even to officers of the court. Among those outside the US, 68% would find the wife guilty.

When can you defend yourself against crime in the street?

I asked about a variety of “crime in the street” scenarios, varying the amount of threat to see when people believe that defending yourself with deadly force is acceptable. What I found is that there are people who would find such force justifiable in almost any situation, and others would find it unacceptable despite the circumstances — and a lot of people for whom the answer is “it depends.”

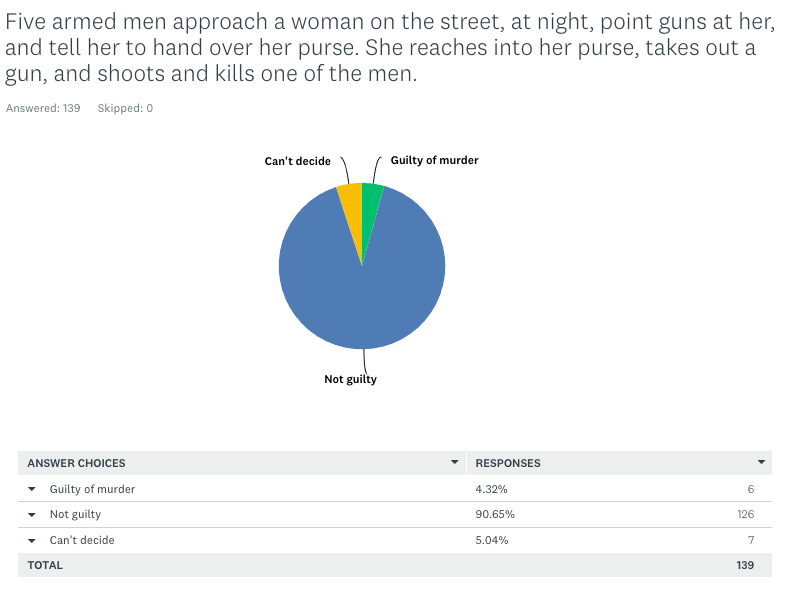

Can you shoot someone who tries to rob you at gunpoint? I thought this was the most obvious self-defense scenario. And such a defendant would not be guilty, say 91% of Americans without legal training, but surprisingly, 6 of 139 respondents would still find this woman guilty of murder. All of those with legal training and 89% of those from outside the US would not find her guilty.

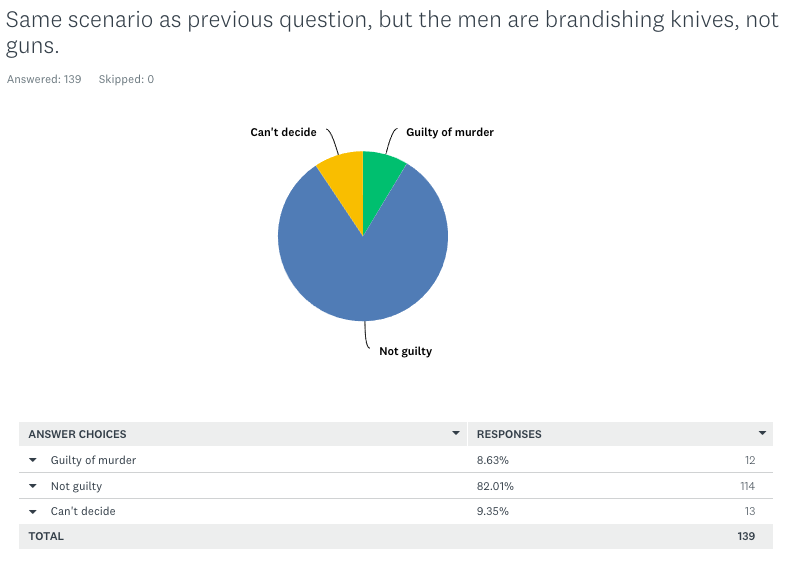

You’re a little less certain if I replace the assailants guns with knives, but 82% of Americans without legal training would still find the defendant not guilty.

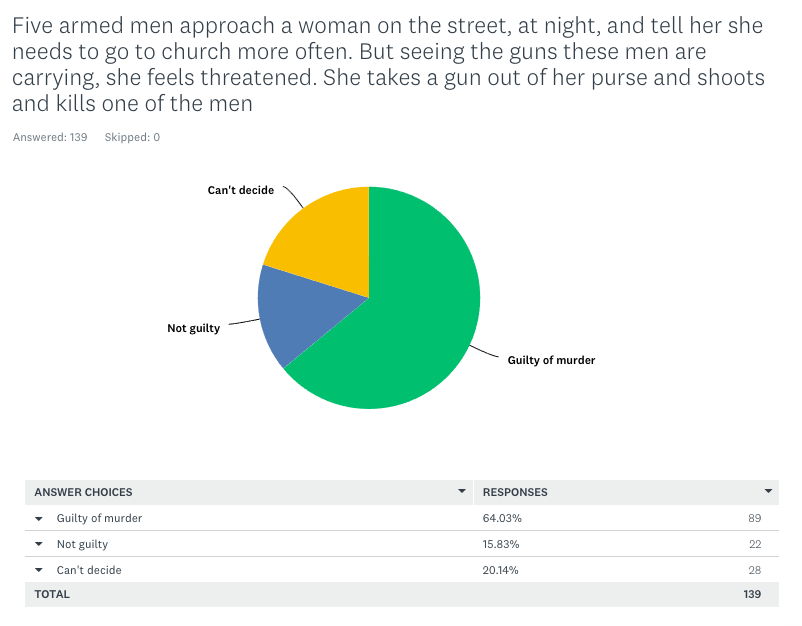

To make this case more difficult, I kept the armed assailants, but this time, they weren’t overtly threatening the woman. Should she be punished if she shoots one? Now 64% of Americans without legal training and 68% of those from outside the US would find her guilty. Interestingly, only two of the 12 American respondents with legal training would agree that she is guilty.

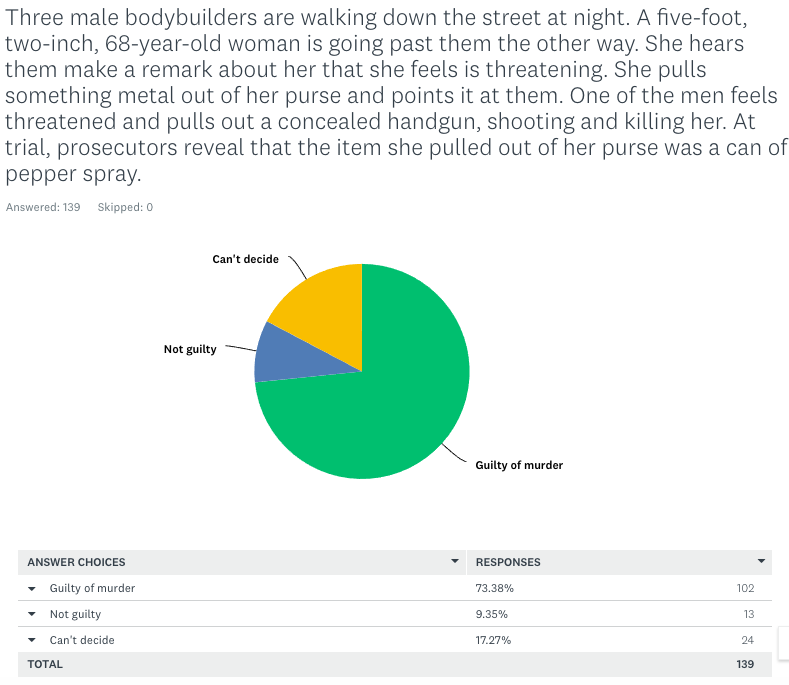

I wanted to see how people would react if I made the threat to the shooter as mild as possible, so I replaced the defendants with bodybuilders and made the threat a little old lady. In that scenario, 73% of US respondents without legal training and 65% of respondents from outside the US would find the bodybuilder guilty. Those with legal training responded about the same way.

What is legal self-defense in a riot?

Given the Kyle Rittenhouse verdict, I was curious about the question of when it is legal to defend yourself with deadly force in a riot. So I created several riot scenarios to see how prospective jurors might react.

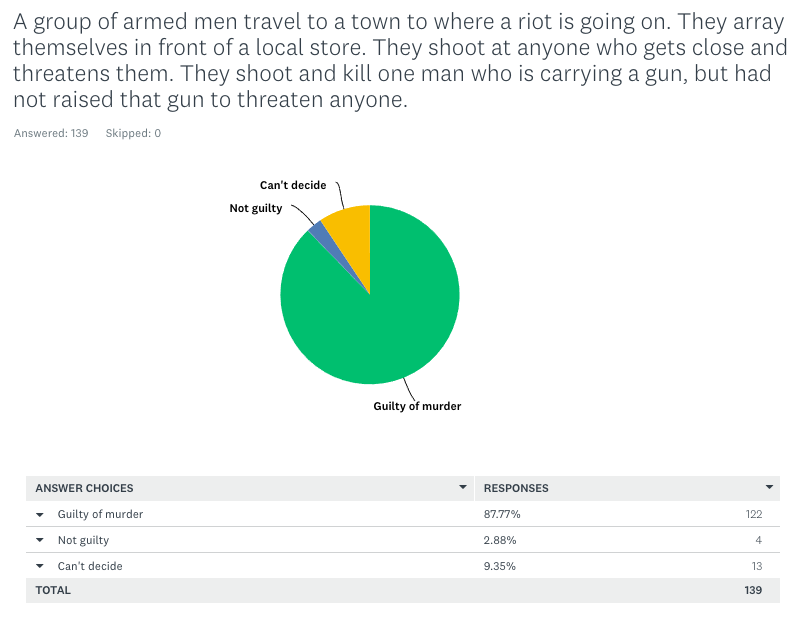

Apparently, nearly all of you believe it’s illegal to shoot armed people who aren’t threatening you, even in a riot. Among Americans, 88% of those without legal training and 92% of those with legal training would find somebody who did that guilty of murder, as would 97% of those outside the US. Who are the four people who think it’s okay for vigilantes to shoot armed people in a riot? Two are male, two are female, three are white, one is Hispanic, and all are 45 and older.

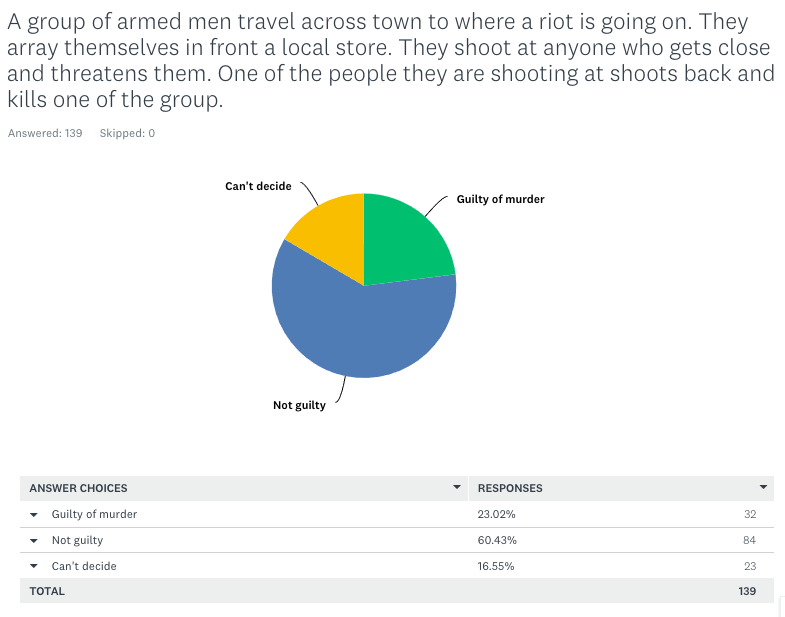

Can you shoot back at people who are shooting at you while defending a store? There was a lot of disagreement about this, with 60% of US respondents without legal training and 75% of those with legal experience accepting a claim of self-defense. But 23% of Americans without legal training would find the people who shot back guilty of murder. Those who would convict the presumed rioters firing at property defenders were 64% male with a median age of 50; none were Black and 12% were Hispanic. Among those outside the US, 70% would find those who shot back to defend themselves not guilty.

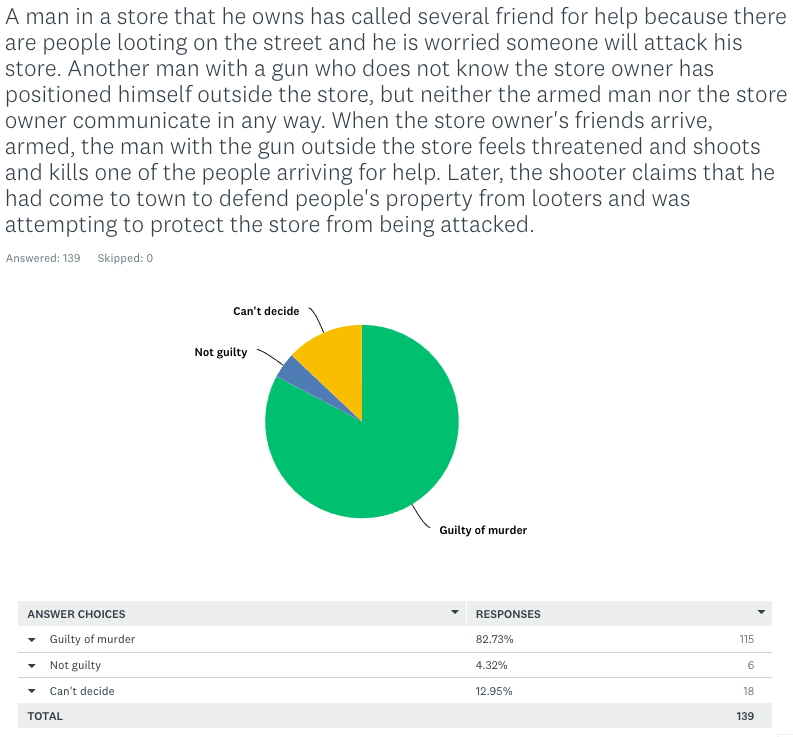

I created this scenario to generate the least possible sympathy for the shooter, who has positioned himself outside a store without the store owner’s permission and ends up shooting the store owner’s friends. In theory, this is similar to the first scenario, since the killer is defending a store and has no way of knowing who they’re shooting. And sure enough, 83% of Americans without legal training and 75% with legal training would convict the vigilante “defending” the store. Among those from outside the US, 81% would vote to convict.

You can’t shoot Arabs, even if you fought them in a war

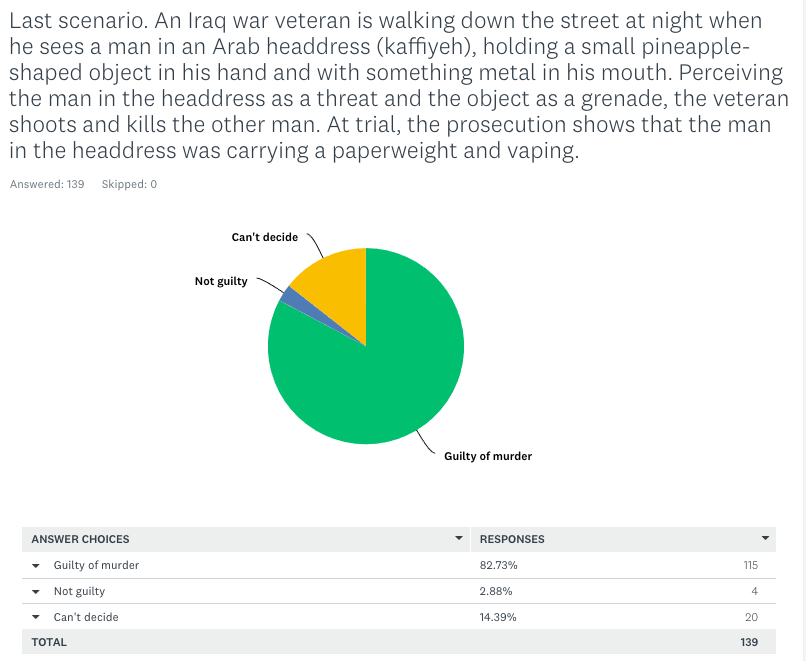

I intentionally left race out of all of my scenarios except the last one, because I don’t believe you can assess racial bias by asking explicit questions. But I did want to create one complex, racially charged situation to see how people reacted. So I presented you with an Iraq war veteran, an Arab, and, at least potentially, post-traumatic stress disorder as a justification for the shooting.

Among Americans without legal training, 83% would convict the deluded veteran, and 14% couldn’t decide — probably because they would need more information about the veteran’s state of mind. Only four people would exonerate the killer here. Responses from those with legal training and those outside the US were similar.

What I’ve learned from this exercise

I wish I had been able to get more respondents and a greater diversity of people answering the survey, but even with this relatively small sample, there’s a lot to learn.

I learned that, at least among my readers and followers, people think hard about the complex scenarios in which people are driven to kill. My respondents were capable of some sophisticated reasoning to distinguish between those who legitimately fear for their lives and those who don’t.

This is in stark contrast to how the media covers these trails, and how the public reacts. Many people examining the Kyle Rittenhouse verdict likely chose guilt or innocence based on their prior political beliefs, and I’m sure the same is true for the Ahmaud Arbery verdict.

It’s certainly true that the proliferation of guns makes these situations more deadly and more fraught. But guns are part of American society now. These events are going to happen. People are going to shoot each other. And juries will increasingly find it difficult to determine who is actually defending themselves and who is just using that as an excuse to kill.

Several of my respondents accused me using this survey to politicize the Kyle Rittenhouse verdict. That was not my intention. By drawing the complex scenarios in contrasting ways — and by limiting the answers to “Guilty of murder,” “Not guilty,” and “Can’t decide” — my intention was to probe attitudes and make people think hard about what it actually feels like to convict or acquit a killer. If you ever have to conduct an experiment like this, I urge you to eliminate as many biases and preconceptions as possible before surveying people. The objective is discover the truth about attitudes, not to confirm your prior notions.

I had no preconceived idea of what the “right” answers would be. I did want to eliminate legalistic interpretations of the answers, because all I was interested in was how people feel, not what criminal legal theory says.

We need to continue to think harder about what is legal and permissible in a violent, armed society. I hope others will pick up on and extend this research, because it holds a mirror up to our attitudes — and reveals that some of them are not nearly as logical as we think they are.

I guess that someone must have done similar research before. Any other results to compare yours with? If you could pick any sample size to adequately examine these questions, what would it be?

I thoroughly enjoyed this entire exercise and admit that I hesitated on many of my answers before submitting my verdict. The results are enlightening. I look forward to participating in another survey “down the road”. Enjoy your day!

The point within the context of the times is that these are hard decisions that require critical thinking especially within statutory and judicial frameworks. In both of the trials in the news, Rittenhouse and Aubrey, the juries made these decisions within their jurisdiction.

It appears that Rittenhouse will be subject to Federal intervention, which will subject the same facts through a different statutory and judicial lens, which may yield much different outcomes. Federal intervention on Aubrey is unlikely.

It is arguable that Federal intervention is a function of the court of public opinion, which views such high profile cases through an emotional, moral perspective that transcends the role of the courts as triers of law and fact.