Treat AI as a slide rule, not a calculator

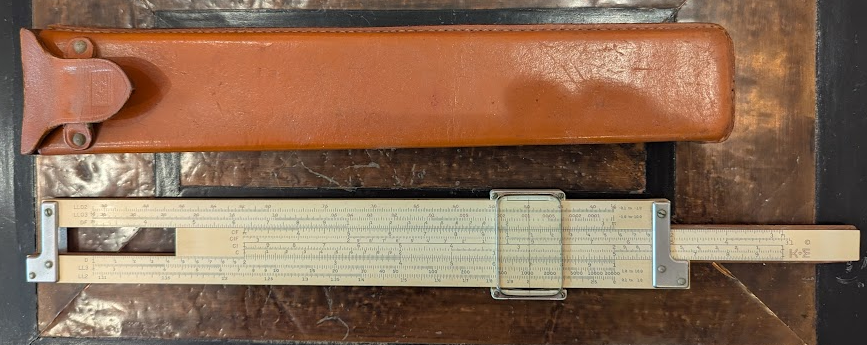

This is my father’s slide rule.

For those unfamiliar with this vintage computing instrument, a slide rule was how scientists, engineers, and technicians did mathematical calculations for much of the twentieth century. You’d carefully align the sliding middle portion with outer frame and read the result off the scales, using the cursor (which was a physical object with a hairline indicating the exact spot to read).

The slide rule had several important qualities. It was versatile: the various scales allowed you to compute logarithms, square roots, trig functions, and so on. It was approximate: if you were lucky, you got the answer to three figures. And it required common sense to read the answer.

For example, if the slide rule indicated an answer of 372, that could mean 3.72, 37.2, 372, or even 372,000. It was your job as the user to know which made sense. If it was the number of grams of sodium produced by a small, precise chemical experiment, the answer was probably 3.72 grams, not 372,000 grams.

My father was a chemistry professor. During his exams, students were permitted to use a calculating device (since he was testing practical knowledge of principles of chemistry, not skill with arithmetic). In the 1970s, most students began to switch from slide rules to calculators. And a funny thing happened to answers on those exams.

When students exclusively used slide rules, if the correct answer to a question was 3.72 grams, most of the answers would be between 3.7 and 3.75 grams. But with calculators, he started to see many answers that were exactly right, but quite a few that were absurdly off — perhaps 24 kilograms, or 0.005 grams.

The student with a slide rule was forced to consider whether the answer they were seeing made sense in the context of the question. But they trusted the calculator to flawlessly give the exact answer, even if that answer was wildly improbable in the context of the problem. They’d outsourced their common sense to a device and ceased to realize that their own mistakes could lead the device to give answers no thinking person should have believed.

AI is not a calculator

When you ask a tool like ChatGPT or Perplexity a question, it finds finds the answer that aligns with its interpretation of your question and its compilation of the answers it can find online. Those answers, of course, can be wrong: hallucinations.

It may tell you that a peregrine falcon is a mammal, when everyone knows falcons are birds.

If you swallow whatever the large language model tells you, you’ve outsourced your common sense to a machine, just like those 1970s chemistry students. Abandoning your common sense is very dangerous.

Instead, like a slide rule user, you need to think a bit about what you’re seeing and decide if it makes sense.

Unlike the slide rule or the calculator, the LLM is biased towards telling you what you want to hear. That warrants even more skepticism.

Check the original source. Many AI searches yield links to sources, but when they don’t, you can ask for one.

Does the source exist? LLMs sometimes invent sources.

Is it credible? LLMs erase the distinction between random crap online and verifiable sources, and can often cough up whatever they find, no matter how unreliable.

Does it actually say what the LLM says it does? LLMs summarizing content in the context of a query will twist the meaning to match the most convenient explanation.

Asking those questions is the 2020s equivalent of using your common sense to interpret what the calculator is telling you.

You’d better get used to this, and make a skeptical view and an awareness of context regular parts of your understanding of the world. In other words, think like a slide rule user, not like someone who believes whatever the calculator says.

AIs are faster and more versatile than any tool we’ve ever had before. But our collective ability to maintain common sense will make all the difference in whether we pass or ignorantly fail the exam of decision-making the modern world.

I had a couple years to hone my slide rule skills in college before affordable calculators arrived. My classmates and I got very good at approximating answers in our heads, because it was essential to check your work at every stage of a complex calculation. Otherwise, you’d end up with nonsense and have to redo the whole calculation, which could take a long time. That skill has turned out to be much more useful than the chemistry I learned and have since forgotten.