The problem with most authors is that they start by writing

In my experience, there are two types of authors: those that start with planning, and those that start with writing. Call them planners and pantsers (seat-of-the-pants writers) if you want.

Both ways work. But the people who start with writing suffer more. If you’re okay with suffering, go for it. But you should at least consider that there’s another way.

What authors told me about their writing processes

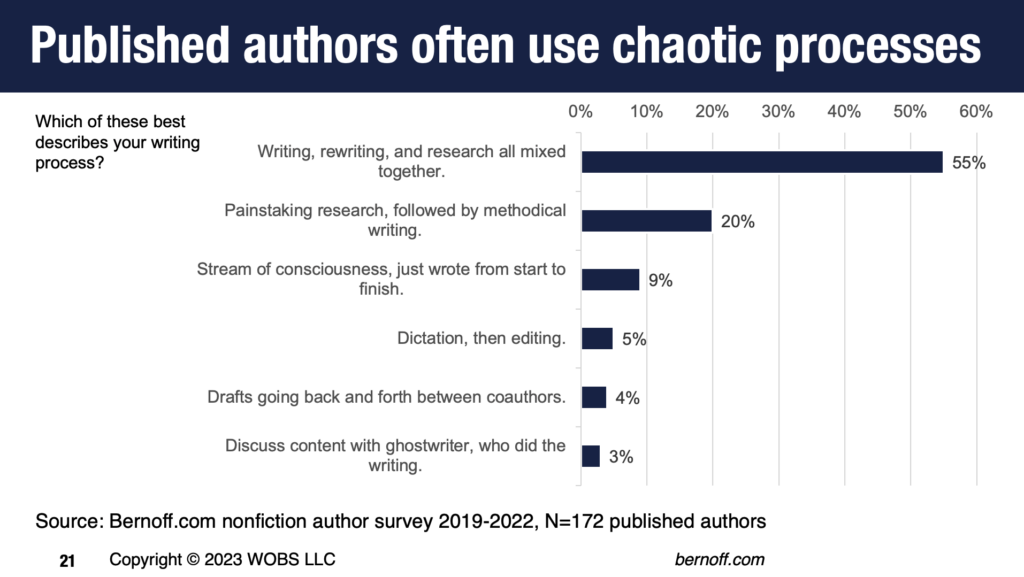

In my recent survey of nonfiction authors, here’s how they described their writing processes:

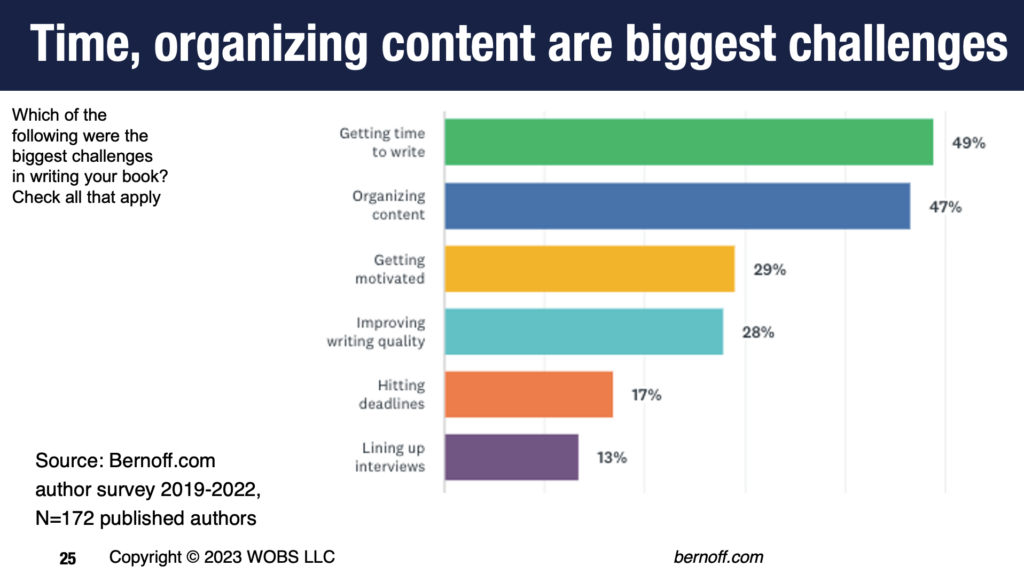

More than half of them treated writing, research, and rewriting as all part of a jumbled process that somehow makes progress towards a finished product. Is that fine? Well, juxtapose that against how authors describe their biggest problems:

After getting time to write, organizing content is the challenge authors cite most often. And among the authors who had a jumbled process, it is the most common problem.

If this is you, I have a pretty good idea what you’re experiencing. You write things. You discard them. You write three passages that all seem to cover the same idea. You start working on a chapter and suddenly find you need a story to make your point. You interrupt your writing to research content online that supports your point, and suddenly find hours have gone by while you were tracking down Web content and quotes — and then later find that the research you did doesn’t really apply to what the chapter actually needs.

This isn’t just frustrating. It also leads to disjointed prose that doesn’t flow.

In the same author survey, 22% of authors said they considered giving up at least once. Given how demoralizing this type of process is, I’m not surprised.

Consider a more deliberate approach

I know you’re a writer. I know that means you may not consider yourself doing “writing” unless you are actually typing. But put that assumption aside for a moment, if you can stand it.

There’s a reason my new book for authors is called “Build a Better Business Book.” Because I don’t recommend starting by writing, I recommend starting by building. Just as the process of creating a building starts with architecture, not bricklaying, the process of creating a book should start with planning, not typing.

Imagine a different process.

Start with defining a fundamental idea for your book, with an audience and a problem you are solving for that audience.

Now define the chapters you are going to write with the reader question method. Consider the big questions your audience has, organize those questions in a rational order, and define chapters that answer each question.

Now get to work on one of those chapters. That chapter will include case study stories, idea frameworks, statistics or other proof points, argumentation, and advice. It’s time to do some research to assemble all those materials. That could take days, but it will be worth it.

Now organize the bits and pieces into a rough fat outline that defines what you’ll use and in what order. This is also where you find gaps and can do additional research to fill those gaps.

Those of you who are jumping up and down while reading all this, thinking, “When do I get to write?” — well, now is when you get to write. But with the fat outline as your guide, your writing will be far more efficient and less wasteful. You’re less likely to complain about the problem of organizing content, and also less likely to want to give up.

But, but, but . . .

Now let’s address the objections people have to this method.

- I like to work out my ideas by writing about them. Great! I’m not stopping you from working out ideas by writing. Consider writing bits and pieces during the research process. Just don’t imagine that your writing has to be laying down prose for a chapter from start to finish.

- What if I change my mind about the order of what’s in the chapter, and no longer want to use the same outline? You are in charge. If you want to deviate from the fat outline as you’re writing, go for it. The outline is a structuring aid, not a straitjacket. But you’ll find that it’s easier to change an existing outline than it is to write without having one.

- What if I change my mind about what chapter to include things in? This happens all the time. But again, you’ll find that it’s easier to restructure the order of chapters, and their content, if you start with a plan than if you don’t have one. Moving things around within a plan makes it a lot easier to see the consequences of the changes you hope to make.

- What do I tell people when they say “How’s the writing going?” Jeeze, if this is your biggest problem, you’re in good shape. Just say “I’m working on ideas and structure right now, the writing stage is coming up soon.”

If you like less stress, less waste, and better results, this sort of planned process is far better.

If chaos makes you happy, just stick with your current chaotic process. But the rest of us will be working a lot more efficiently — and we’ll be able to spend more time with our families on nights and weekends, too.