What do the Republican tax proposals really mean?

Congressional Republicans, egged on by Donald Trump, are debating changes in the tax code. Any number of pundits on both sides have weighed in, as have tax wizards at think tanks and, strangely, press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders with a bizarre argument based on reporters buying beer.

The analysis tends to focus on who wins and loses. I think that’s the wrong emphasis. For each of the proposed changes, there is a question behind the question. What do these changes say about what we think is really important in America, or about our philosophy of government? From my naive perspective, I’m going to try to unravel the real questions rather than the ones you typically hear in the articles about this tax plan.

What will tax cuts do to America?

The nonpartisan Tax Policy Center’s (TPC) original estimate was that that the plan would reduce revenues by $3.1 trillion in the first decade. Reducing taxes also boosts the economy as consumers and businesses spend some of the money that they don’t pay in taxes — but remember, if the U.S. government had that money, it would spend it as well, so much of it would go into the economy in any case.

Do tax cuts generate so much additional taxable economic activity that they pay for themselves? According to TPC, “At current tax rates, the direct revenue loss from tax cuts almost always exceeds the indirect gain from increased activity or reduced tax avoidance. Tax cuts can, however, partly pay for themselves.” Only the most extreme of economists believe that you’ll end up with more tax revenue in the long run after making significant tax cuts.

So let’s assume that the government will end up with trillions of dollars in less revenue. The Republican calculation agrees with this — to pass the tax plan under current Senate rules with no Democratic votes, the total amount of lost revenue cannot exceed $1.5 trillion over ten years.

The real questions here: Is reducing government spending a good idea, or will it hurt too many people? Also: Is increasing the national debt to fund tax cuts dangerous?

If you don’t trust government to spend money wisely, then giving that money to consumers and businesses seems like a good idea. This is the Republican argument.

If you think the reduction in government spending will interfere with essential government services that we all enjoy — appropriately staffed business regulation, services to disadvantaged people and veterans, and spending on national defense, for example — then huge cuts in government seems like a bad idea.

Inevitably, given the way Washington works, after tax cuts the government will cut some spending and finance the rest with borrowing. Excessive government borrowing drives up borrowing costs for business, reduces the strength of the dollar, puts us in debt to countries like China, and can lead to inflation. Deficit spending hasn’t had big ill effects so far, but there is some tipping point at which it will, and no one knows where that point is.

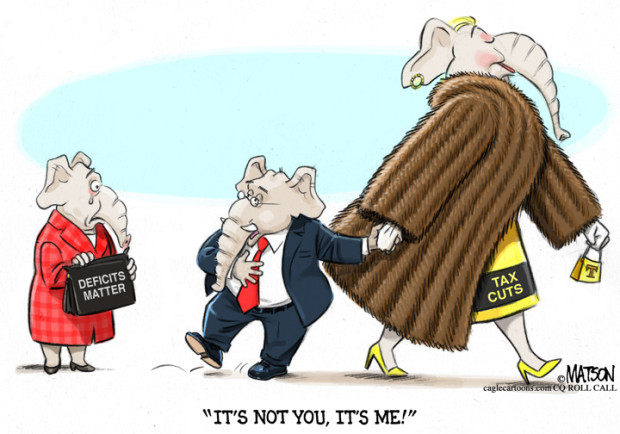

Conclusion: The tax argument should be about reduced government spending and increased debt, not just tax cuts. We’re not discussing the result honestly.

How will businesses spend their tax cuts?

Current corporate tax rates top out at 33%. The Republicans want to reduce that to 20%. The government would tax sole proprietorships and partnerships that pass though their tax to people’s individual tax forms at 25%.

The real question here: What would a business do with money saved from reduced taxes?

Republicans believe such businesses would spend or invest money. Opponents believe that they’ll hold on to the money, which will increase the value of their stock and benefit shareholders. This matters, because if Republicans are right this will increase economic activity and benefit everybody, and if their opponents are right the only beneficiaries will be people who can invest — rich people.

if you’re in a competitive business — like selling mobile phones or breakfast cereal — you might spend the additional money to try to get an edge and grow your market share. If you’re a cable company or Facebook, I can’t see how this cut would change how you spend money.

What about all the small businesses? I’m one. This tax cut would decrease the taxes on my little consulting business. I’d spend some of that money on my business and also pay myself a higher salary. I’d use that higher salary to buy some things, and invest some for my retirement. I think a lot of small businesses are in the same boat — they’ll spend a lot of what they don’t pay in taxes. They’ll increase wages if they’re competing for skilled workers, but not if they’re using minimum-wage unskilled people.

This differential will of course drive many people to create pretend businesses to reduce their tax burden. It’s ironic that past budget cuts have reduced the IRS budget, which makes it harder to find and stop abuses like this.

Another real question: Why aren’t we fixing all the loopholes and exceptions in the corporate tax code?

The tax code is special provisions that are intended to make businesses behave in certain ways. Big businesses hire armies of lawyers and accountants to manipulate their incomes based on these rules and pay as little tax as possible. The architects of the GOP plan have spoken very little about all these special rules.

Because of corporate lobbyists, special tax rules for companies are hard to change — that’s the hard work, and we’re avoiding it.

Conclusion: Business tax cuts will help the economy, but that won’t necessarily help the average person make more money or get a better job. And we’re avoiding the real challenge of getting rid of all the bizarre incentives in the corporate tax code.

Is increasing the exemption a good idea?

In the new plan, everybody gets to exempt $12,000 to $24,000 of income from taxes, depending on if you’re single or married. That’s double the current amount.

A lot of low-income people don’t pay tax at all. This is no help to them.

It helps everybody else in pretty much the same way — the won’t pay on the first big lump of income.

One thing this does do is reduce the number of people who itemize their deductions. This makes charitable giving less beneficial, and it also undermines the incentive for home ownership that the mortgage interest deduction creates.

The real question: Is benefiting middle-income people and simplifying their taxes worth getting rid of incentives for home ownership and charity?

If you’re going to do a tax cut, this is one that Democrats and Republicans ought to be able to agree on, because it will make a proportionally bigger impact on middle-income households, and save proportionally less on high-income households.

Conclusion: If you think tax cuts are a good idea, the exemption is a good place to start.

Is it a good idea to eliminate the deduction for state and local taxes?

To keep the cuts from reducing revenue too much, tax cutters need to look for deductions to reduce or get rid of. They treat the mortgage interest deduction as sacred, because people bought houses based on it. In a world where house prices are rising so rapidly, partly as a result of this deduction, it’s not clear this deduction is a good idea, but no one has the courage to even talk about it.

The other deduction currently under discussion is the deduction for state and local taxes. In other words, if you pay $3,000 to the state of New York or the town where you live in property taxes, then you don’t need to pay tax on that. That always seemed fair to me, since you shouldn’t have to pay tax on those same dollars twice.

The real question: Is it fair for people to pay federal tax on money they already pay in state and local taxes?

Eliminating this deduction would reduce the cost of the tax cuts significantly, but create holy hell in states like New York and Massachusetts where local taxes are high. Tax cut enthusiasts say this will cause local governments to spend less. Opponents say it’s not fair to penalize residents of those states for taxes they’re paying for local services.

Conclusion: Eliminating this deduction isn’t fair.

How high should the top tax bracket be?

Right now, the top tax bracket — the tax rate that the highest earners pay on the high end of their incomes — is 39.6%.

The Republicans’ original proposal reduced the top tax rate to 33%. This would help earners in the highest quintile avoid an average of $11,760 in taxes, and those in the top 1% to avoid $212,660, according to TPC.

The real question: Should rich people pay tax at a lower rate?

The Republicans are now discussing keeping the top tax bracket at 39.6%, but having it kick in at much higher income.

If you think that rich people spend money when they have it, then reducing their tax rate is a good idea. But evidence shows that the richer you are, the more of your money you invest, rather than spend.

The new Republican proposal would still save these rich people money, but not as much — and its impact on people with the highest incomes will be less than what would happen if the top tax rate came down.

Conclusion: We shouldn’t reduce the top tax bracket.

Is repealing the individual health insurance mandate a good way to cut taxes?

Donald Trump has suggested getting rid of the penalty that people pay for having no insurance. On the surface, this looks sort of like a miracle. It reduces taxes on low income people (specifically, the penalty they pay for having no insurance). But it also saves the government money, because fewer people would be getting Medicare or insurance subsidies. Score!

Of course, there’s a problem. If you eliminate this mandate, healthy, young, low-income people won’t get insurance. This removes revenue from insurance markets and increases the cost of insurance for the rest of us. It basically spells the end of the Affordable Care Act.

The real question: Is it a good idea to destroy the Affordable Care Act in a tax cut plan?

Congressional Republicans aren’t going to go there. Once you tie the tax cuts into health insurance changes, it becomes close to impossible to get the votes to support them.

Conclusion: This is a dumb idea. If you want to fix health care, you have to fix health care, not sneak changes into a tax bill.

What this all means

I’m no economist. But I’m fascinated by this debate. I haven’t even gotten to some of the other provisions, like rule to allow companies to repatriate income they’ve parked overseas and eliminating the estate tax.

Don’t be fooled by the left and the right framing this up with their arguments about who wins. Concentrate on the real question: what are we going to go without if we spend less money, or are we just going to blow up the debt? And if you cut taxes, will the people and companies spend their money or just hoard it?

Josh, you’ve done a fine job simplifying an otherwise politically loaded debate – your points are sound AND objective. As with healthcare, I fear well financed lobbyists will render “reform” impossible; we’ll wind up with a modestly simpler tax code with deduction phase-outs. Let’s hope, at least, that we can finally rid ourselves of the unmentioned AMT – Alternative “maximum” tax code.

Since you and I have different points of view on politics, I’m pleased you see this as objective. That was my intention.

And yes, I left out the AMT. My cousin the liberal economist and you would agree on the stupidity of the AMT, which has no remaining constituency now. Begone!

Health Care BS. The prices and plans went up with that creepy Obamacare.

I am working like a slave, driving 120 miles a day to take less of my paycheck home that I did in 1998,… for what to maintain a bunch of bullshitters in welfare.

I can not be sick because my plan is asking me to meet a deductible of $3000 before my plan takes in the 80% of medicine cost.

BS Obama case.

I’d be interested in seeing you dissect the 2-pager the Ways & Means Committee put out today. A lot of squishyness in that one, including the phrase “death tax,” and several mentions as to what they aren’t changing.

I’m curious on why you think this is important?

“And if you cut taxes, will the people and companies spend their money or just hoard it?”

I understand the economic implications, but consider the question null and void as the money belongs to folks, who have the right to do either.

Thanks,

Norman

The context here is making America great again — this tax cut is supposed to unleash growth. Growth needs jobs. Jobs come from spending not hoarding.

Always a pleasure, Norman.