Protecting government statistics

Two things are true. One: that many of our most important decisions depend on data generated by the government. And two: regarding the people who produce the government data, president-elect Trump has promised that “As many as 100,000 government positions can be moved out — and I mean immediately — of Washington.”

Here’s why that scares the crap out of me.

A cautionary tale from Argentina

Like nearly all nations, the country of Argentina has an official agency dedicated to tracking government statistics including inflation. It’s called INDEC, which is the acronym for a name that translates from Spanish as “Argentinian National Institute of Statistics and Censuses.”

In 2006, Argentinian government minister Giullermo Mota became determined to influence the inflation statistics that were used to calculate Argentina’s required government interest payments — and to make it appear that the Argentinian economy was better off than it actually was. He met with technicians at INDEC and asked at which retailers and for which items INDEC was tracking prices, likely with the intent to pressure the people reporting those prices to cook the books. INDEC officials explained that their policy required them not to reveal the contacts Mota had requested.

He then attempted to pressure INDEC to change its inflation calculation algorithm, but because INDEC publicly reported its methods, observers would have instantly detected and criticized this tampering. Eventually, in 2007, the Argentinian government removed INDEC’s administrator and replaced her with someone who would follow orders. INDEC’s new leadership excluded all price increases greater than 15% and replaced them with alternate data sources. The reported inflation diverged further and further from what consumers were experiencing, and press and analysts ceased to believe Argentina’s official inflation statistics.

By 2013, the International Monetary Fund officially stopped giving any credence to Argentina’s official statistics and cut off the supply of funds to the government, hampering the country’s ability to recover from its economic crisis. Other organizations doing business in Argentina lost faith, because there was no credible way to measure the health of the nation’s economy.

The tampering with statistics may have looked useful in the short term, but in the long term it created far more intractable problems for Argentina than the inflation had.

What statistics does the federal government provide, and why should you care?

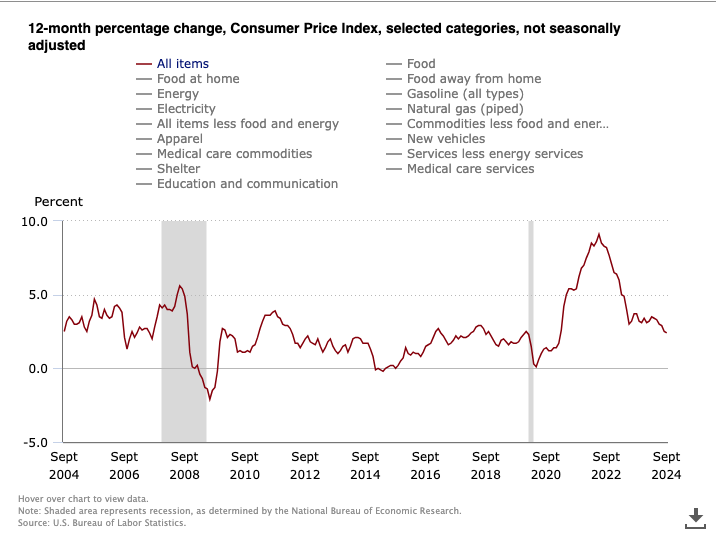

The Bureau of Labor Statistics collects and publishes data on inflation, unemployment, and economic growth. When you read official reports of those numbers in the news, that’s where they come from.

The FBI reports crime statistics.

The CDC (Centers for Disease Control) reports health statistics.

The NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) reports weather data.

There are countless other parts of the government collecting and reporting official data on a regular basis. It’s part of what our taxes pay for. (If you want to see an attractive presentation of some of those stats, check out USAfacts.org.)

All of the data is imperfect. There are always flaws and uncertainties and, occasionally, errors. But all of the data is collected using transparent methods, like surveys and sensors, and the algorithms used to calculate statistics are publicly visible.

These numbers are important. The Federal Reserve uses them to calculate whether to change interest rates. Investors use them to calculate where the market is going. Politicians use them to decide where to invest government funds. States use them to determine who is eligible for food assistance. Health officials use them to assess the effectiveness of treatments. FEMA uses them to predict where hurricane and flood aid may be needed.

There is continuity in these statistics. Inflation calculations don’t change based on who is the president, and weather forecasts don’t change based on requests from senators in affected states.

Politicians have always cherry-picked and criticized the methods of the officials publishing government statistics, because those numbers can make the politicians look bad. But they represent reality, or at least as close as we can come to modeling reality with the methods the government has at its disposal.

The problem is almost always reality, not the statistical methods or the people who collect and report them.

It’s easy to call the people who report these statistics part of the “deep state.” If President Trump does what he attempted to do at the end of his last term — reclassify tens of thousands of civil servants according to a policy known as Schedule F and replace them with employees loyal to the president — then these statistics are at risk.

I don’t want my weather forecasts changed with a Sharpie if they don’t agree with what the administration would like them to say.

And I don’t want my inflation and unemployment figures, my assessments of the effectiveness of health treatments, or my crime data jiggered based on the political needs of the moment.

Regardless of what you think of the American economy, we’re a lot better off than Argentina. I’d like to keep it that way. So let’s keep the government statistics the way they are, free from partisan tampering.

It may not seem like a big deal, but once that foundation of dependable data is gone, none of us can make smart decisions. And that’s a prescription for disaster.

Couldn’t agree more. Thank you for continuing to fight for fact-based public information!