Need to repair and edit a big, messy, disorganized manuscript? Try using sticky notes.

You did it, didn’t you.

You wrote a nonfiction book (or most of one). Now you have 50,000, 70,000, maybe 100,000 words. And it’s a mess. You’re feeling desperate. You can’t start over — but how can you turn this mass of goop into something useful?

Don’t despair. It’s not as bad as you think. I’ll explain how to fix it.

Two ways to write a book

People think the best way to write a book is to start writing.

Nope. The best way to start is to refine the idea, develop a detailed table of contents, and write a sample chapter.

But some people can’t seem to get their heads around that. They’d rather write and write and write, because it feels more productive.

This is certainly not the most efficient way to write a book, but it does have benefits. It gets what’s in your head out on the computer screen. It shows you what you have to work with.

Do this and you’re still way ahead of the person who hasn’t written anything. Editing is easier than writing. But it’s still work.

How to do a developmental edit — the sticky note method

The instructions that follow apply whether you are the developmental editor helping a writer, or you are the writer editing yourself. The method is the same. I’ve used it on my own manuscripts and, more frequently, on poorly organized messes from other authors. It works pretty well and as an added benefit, it gives you the chance to discuss the proposed new organization of content before you start rewriting.

First, recognize that you can’t fix a big disorganized manuscript by starting at the first sentence of page 1 and editing sentences. If you edit the text one sentence at a time, you’ll just have a slightly better written mess.

No, you need to take inventory.

Gather up a set of pads of different colored sticky notes. For this exercise, the best size is 3 inches square. You probably need at about five different colors.

Each note is going to represent a type of content in your manuscript. For example:

- Pink is a case study.

- Yellow is a personal reminiscence.

- Blue is a set of proof points based on research.

- Orange is argumentation intended to prove a point.

- Dark blue is a description of a concept.

- Purple is a graphic.

Depending on what your manuscript includes, you can create your own classification of content. You may need fewer categories, or more, but don’t exceed seven or eight content types.

For this to work, your existing manuscript needs to be divided into chapters. (If it is one big long file, you have my sympathy — but please divide it up now in some logical way into separate chapter files.)

Take inventory of your manuscript

Here’s how to take inventory.

Starting at the beginning of your first chapter, identify what you wrote. For example, maybe the first two pages are personal story about how you learned to drive your first car. Take a yellow sticky note (if you are using yellow for personal stories) and write “Learning to drive, Chapter 1” on it. (The “Chapter 1” will make it easier to find this bit later when you need it.)

Put that sticky note aside and read the next piece of your chapter. Maybe it is a description of your main concept. If you’re using dark blue for concepts, write the name of the concept along with “Chapter 1” on a dark blue sticky note, and put it aside.

Continue this for every chunk of content in the chapter. The right size chunks to index in this method are 100 to 700 words — typically two to ten paragraphs. If you have parts that continue what you wrote before, make a separate note for that (“Continuation of learning to drive, Chapter 1”).

Do this for the whole manuscript.

If you don’t write in a modular fashion and things tend to bleed into each other, this exercise may be difficult, but do the best you can.

Since you are closely reading the whole manuscript, this inventory exercise can take at least a couple of hours, perhaps up to eight or ten. But it’s absolutely necessary. You need to know what you have.

Once you have completed this exercise, you’ll become aware of a number of key things.

- How many chunks of content do you have in total? The answer is likely between 50 and 120. It’s a lot easier to think about 100 pieces of content than 70,000 words of text. You should already be feeling a little better.

- What types of content do you have? Is your manuscript 30% case studies and 70% argumentation? How many concepts have you introduced? Simply by looking at the distribution of colors in your sticky note collection, you can get an idea of the ingredients in what you’ve written.

- Is there duplication? Did you tell the same story in Chapters 3, 5, and 8? Organizing and culling repetitive content is a crucial developmental editing task, and now you have the knowledge to do it.

- What themes do you hit on frequently? Maybe there are seven notes all about getting the right mental attitude, or eleven about preparing properly before executing tasks. Think now: do these all belong in one place, or should they be recurring element throughout the chapters?

- What’s missing? Even if you wrote 100,000 words, you are likely missing pieces. Did you notice things you wish were there? Create a sticky note for the missing piece (e.g. “Tesla story, To come”) and include it in the collection.

Do an idea development audit

It’s likely that while writing your manuscript, your idea of what your book is about changed.

You may also have new ideas about the book based on the inventory you just completed.

Before you launch into organizing or reorganizing the book, take some time to reconsider the title, subtitle, and main theme of your book. What is it really about? This far into the task of writing it, it’s likely that you know.

If you’re still uncertain, it might be time for an idea development brainstorm with a colleague. There’s no better time for that then now — you’ve got all the content in your head, and you’re about to launch into a rewriting exercise that will benefit from a clearer idea of what the book is about.

Reorganize notes into a table of contents

It’s time to plan.

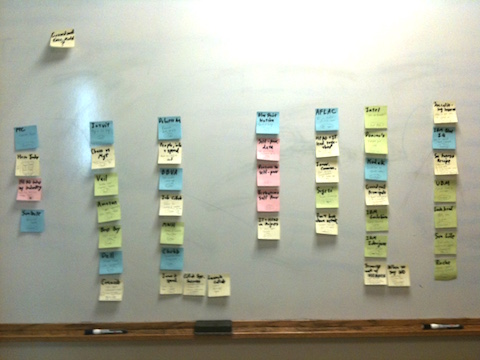

Find a large blank surface, such as a big table top or a whiteboard. (If you work from home, this is the perfect time to take advantage of your rarely used dining room table, if you have one.) You can even use a blank wall.

Then take your sticky notes put them up there. Then organize them into chapters. You’re now creating what will be your table of contents.

How should you organize the chunks of content? Start with a set of content that challenges people — make Chapter 1 the “Scare the crap out of them” chapter.

What concepts are important to come next? You can arrange the other chapters into an order that makes sense, for example, “Why it’s important, how to do it, detailed instructions.”

Think about what questions each chapter can answer for the reader, such as “What are the key steps in digital transformation?” or “How can I convince my boss to change our working relationship?”

Moving around big hunks of text seems fateful and dangerous. But moving around sticky notes is easy. You can move content from one chapter to the next with minimal effort. And if you don’t like how it looks, you can move it right back.

If you have a coauthor, it’s a lot easier to collaborate on a set of sticky notes than a huge text manuscript that you’re reorganizing.

Here is also where you find and collect duplicated material and decide what chapter it belongs in.

Try not to get sucked into the gravitational attraction of the organization you already have. You’re unhappy with that because you know it’s not the right organization. Here is where you try some different ways to organize the text.

You’ll inevitably find that you have too much material in some chapters and too little in others. Don’t worry about that yet; it’s valuable information for the next step.

Organize the material in the chapters

Now that you think you know what’s in each chapter, you can organize each chapter in a rational way.

Most of the chapters are likely to fit into a template, for example: opening case study, followed by main concept, proof points or justification, helpful tips, optional additional case study, and final comments. Your sticky notes will tell you the ingredients you have to work with — now put them in a rational order.

The organization within the chapter should reflect a logical, story-based approach. For example, show a customer story, explain the questions that it raises, suggest an answer to those questions, show how to implement that answer. There has to be a thread to the chapter that the reader can follow.

It is at this point that you may realize that some chapters are missing pieces — you’ll have to create placeholders for those.

As for duplicated material, just gather it all in one place. When you actually get into rewriting, you’ll rationalize those pieces.

Don’t be afraid to reorganize the chapters from the previous step based on insights you get here. Since you haven’t rewritten anything, the cost of reorganization at this stage is minimal.

You are likely going to find some stickies representing content that has no place. Ask yourself, “do I actually need this?” Gather the unused stickies in a separate place. You may find you can use them later, or turn them into promotional blog posts, or just dump them altogether.

You are now done with the restructuring process. I suggest using paper clips to keep the sticky notes in sheafs, one for each chapter. You could also transpose the organization of the sticky notes into an online format.

Why not just do this all online?

In theory, you could do everything I suggested without sticky notes. You could organize your content into a spreadsheet and move it around there, for example.

I still think the sticky notes are better, though. It is freeing to move the notes around separate from content, and separate from distractions on your computer. And I think the physical format of the notes helps you think of the organizational task independent of the way you think about things on your PC.

If you’d rather do this online, the process is still the same — you’ll just be reorganizing spreadsheet entries rather than sticky notes.

Now revise and rewrite

The benefit of the sticky note method is that is separates the organizational and structural issue from the content editing issue. When you are done with the organizational planning, you can begin the rewrite, which includes editing improvements.

Start a new file for Chapter 1 of the new draft. Take your sheaf of sticky notes and identify the first chunk you need. Copy it from its old location and paste it into the draft. Then edit it based on its new position within the manuscript, fixing any terminological, consistency, or writing issues as you go along. Find the next chunk, paste it in, and edit it, including a transition from the previous chunk if needed. Continue like this to the end of the chapter, and for each subsequent chapter.

You’ll have some more difficult work to do here, for example, writing missing pieces and combining and rationalizing duplicated content that you’ve brought together.

And you’ll need to keep a close eye out for effects of the new order of content. For example, you can’t use concepts in Chapter 2 that you don’t define until Chapter 4. And you need to nail down forward and backward references based on the new chapter order.

That’s a lot of work.

But by using the sticky note method, you separate the organizational work from the revisions. That will give you a lot better visibility into what you are doing and where you are going. And it will likely keep your spirits a little higher as you turn your mess of a manuscript in a publishable masterpiece.

Order the sticky notes now (or go get them from your office supply cabinet). And get to work. You can do this!

In 2010, I was writing without a plan. Aimless is a good word to describe it.

Once I landed on a title and topic, I junked 40 percent of my manuscript, and everything crystallized. The New Small isn’t my best book, but at least it revolves around a coherent thesis.

I didn’t use Post-its, but maybe I should have. Regardless, I never made that mistake again for embarking on a long-form writing project.

I like the idea of sticky notes.My problem is I have too many.Maybe using different colours would help. I find i’m writing up these chapters and then I find some chapters should move up in the story.I would have to change so much.I also come up with more details for some of these chapters and I’m thinking I’m probably way over the word count. I’m still working on chapter two and ten scenes. Nowhere near the finishing this Non Fiction novel. I’m also feeling blocked at times.