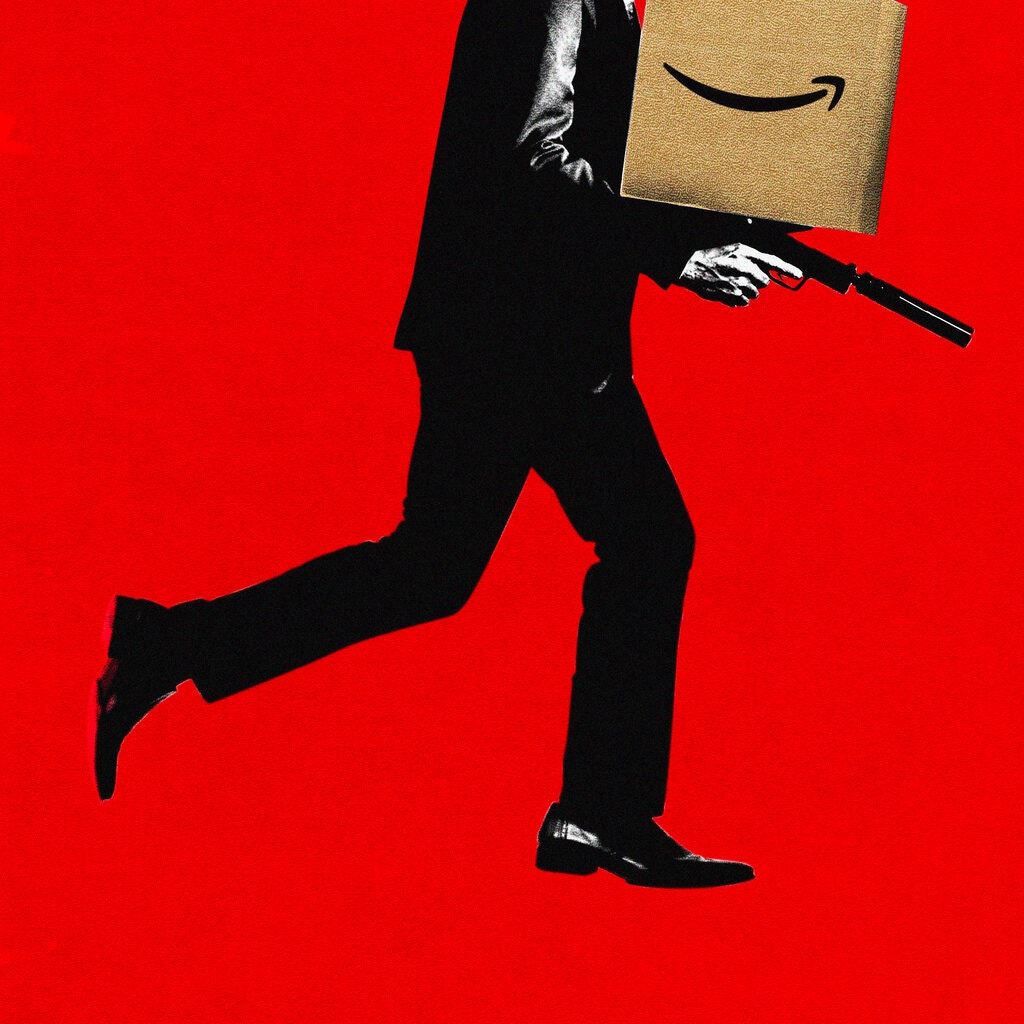

James Bond, creativity, listening, and data

John Logan, the scriptwriter behind two of the latest James Bond movies, is worried that when Amazon buys MGM, it will ruin 007. But data and corporate control doesn’t necessarily ruin creativity. It all depends on who’s making the creative decisions.

John Logan’s lament for 007

Here’s some of what John Logan, co-writer of “Skyfall” and “Spectre” — as well as screenplays for such amazing movies as “Gladiator” and “Hugo” — wrote in The New York Times.

The reason we’re still watching Bond movies after more than 50 years is that the family has done an extraordinary job of protecting the character through the thickets of moviemaking and changing public tastes. Corporate partners come and go, but James Bond endures. He endures precisely because he is being protected by people who love him.

The current deal with Amazon gives Barbara Broccoli and Michael Wilson, who own 50 percent of the Bond empire, ironclad assurances of continued artistic control. But will this always be the case? What happens if a bruising corporation like Amazon begins to demand a voice in the process? What happens to the comradeship and quality control if there’s an Amazonian overlord with analytics parsing every decision? What happens when a focus group reports they don’t like Bond drinking martinis? Or killing quite so many people? And that English accent’s a bit alienating, so could we have more Americans in the story for marketability? . . .

From my experience, here’s what happens to movies when such concerns start invading the creative process: Everything gets watered down to the most anodyne and easily consumable version of itself. The movie becomes an inoffensive shadow of a thing, not the thing itself. There are no more rough edges or flights of cinematic madness. The fire and passion are gradually drained away as original ideas and voices are subsumed by commercial concerns, corporate oversight and polling data. I wonder whether such an outré studio movie as “Vertigo” would have survived if such pressures existed then. Not to mention radical films like “Citizen Kane,” “The Red Shoes,” “Cabin in the Sky” and “Bonnie and Clyde.”

Logan goes on to describe how fierce directors like Ridley Scott (“Gladiator”) and Martin Scorcese (“The Aviator”) fended off “suggestions” that would have undermined their creative visions.

Creators listen. They don’t cave.

My wife and I are creative workers. So are my author clients. We care fervently about what we create. I won’t work with anybody who doesn’t care this way.

All the time, I read advice for writers that looks like this: “Don’t compromise your creative vision. Don’t give in. Don’t give up. Ignore rejection. Push forward.”

This is such bullshit. It really misses the point of how creativity works.

The creative artist does not just imagine something and create it in a vacuum. There are always obstacles. If there are no obstacles, the story will be boring. Creating is never easy.

There are, of course, the internal obstacles. For example, when you notice that you’ve written the same scene twice in different parts of the work. Or when the laws of physics make your plot impossible. Or when you just realize that the text is rambling onward and needs a major trim.

But there are external obstacles, too.

There are editors who will tell you to change what you wrote because it is unclear, to cut parts that don’t work, to rearrange content to be better organized, or even to fix what you wrote because you’ve violated grammar rules.

There are friends who will give you all sorts of advice after reading your work, often contradictory.

There are clients who, after you road-test the content with them, will reveal where the weaknesses are.

There are sometimes people who are bankrolling the work — like publishers and producers and studios. They have suggestions. You can’t ignore those suggestions, because there is the implicit threat that they’ll stop funding you . . . which is what John Logan is worried about.

Finally, there is data. You can collect information about your target audience. You can learn things. You can test ideas. And sometimes, the data suggests that you’re headed in the wrong direction.

True creators find none of these things threatening. These pushbacks create challenges, but challenges make things better.

The true creator has an internal vision so clear and heartfelt that none of these challenges can shake it.

That confident creator welcomes these challenges. When the editor says “it’s too long,” the creator figures out what to cut to make it shorter.

When the person holding the pursestrings insists on a change, the confident creator figures out how to address the underlying concern that suggestion reflects, without compromising the creative core of the work.

When the road-test of the idea reveals a problem, the confident creator relishes the opportunity to fix that problem. “I’m sure glad I fixed that before it got released,” they say.

The confident creator welcomes data. The confident creator loves data. Data suggests new ideas. New ideas make things better.

Art thrives under pressure. Challenges make it better.

This is how Alfred Hitchcock was able to create the shower scene in “Psycho,” despite the limitations imposed by censors. In that scene, you never see the knife enter the woman’s flesh. You never see a wound. There is no actual nudity. You feel the terror, but there is no gore. Hitchcock found a creative solution to an external problem — what censors would object to — and the resulting 52 edits in 45 seconds with screaming violins on the soundtrack made the work better. (Do you think “Psycho” would have been scarier with actual stabbing? I don’t.)

Your response to challenges like these works only if you, the creator, perceive criticism, suggestions, data, and limitations as opportunities, rather than threats.

Be the confident creator. Then you don’t need to worry about who owns the studio or who’s publishing the book or what your boss says or what the analytics reveal or what the censors will allow. You’ll take all that in and address it to make what you’re creating better. And everybody else, including your corporate sponsors, will treat you like you’re Martin Scorcese or Ridley Scott or Alfred Hitchcock — or Barbara Broccoli, the keeper of James Bond’s legacy — because they’ll have absolute confidence in your ability to respond with a better result. They’ll admire you, rather than seeing you as “difficult.”

Of course, you could stick to your narrow view in the face of all criticism and data — and build something only you will like.

Or you could do everything other people suggest, lose control of your project, and make something ordinary.

Please don’t do either of those. Maintain your vision and learn how to listen. You’ll be happier and the art will be better.