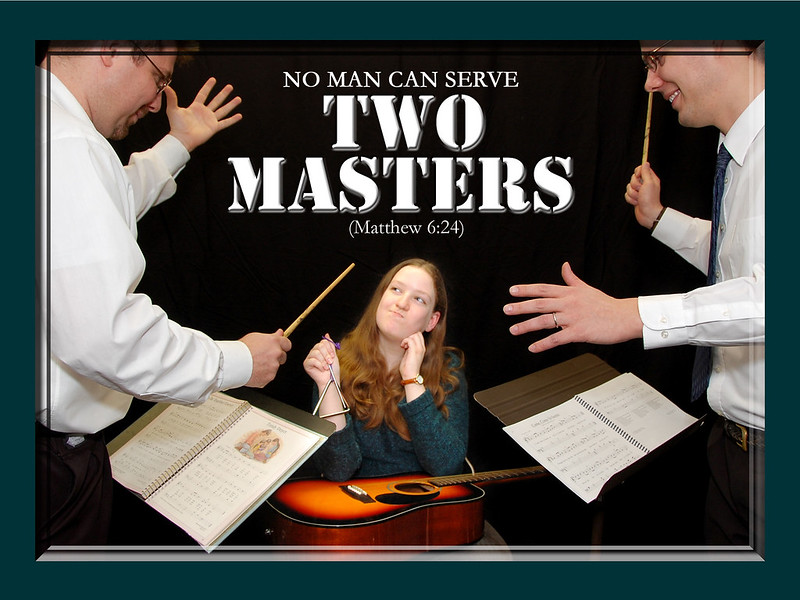

How writers can efficiently serve two masters (or more)

Whether you’re writing in a corporate setting or as a freelancer, you’re likely to face this common issue: multiple “client” individuals that you must satisfy before the project is complete. How can a writer serve more than one master?

In my experience, this is both extremely common and very tricky. In the business writer survey I conducted, less than one in three writers thought they had a process for managing reviews that worked well.

I’m facing this right now in two of my projects: developing a book idea for two executives and their head of communications, and ghostwriting a book for a CEO and his team. I can tell you this from long experience: if you don’t prepare for the challenge of managing multiple reviewers, you’re in for a world of misery.

Best practices for writing for multiple masters

Here’s what you can do to minimize misery and maximize success for project with multiple clients:

- Figure out who the alpha dog is. There is almost always one primary individual who you have to satisfy with your work. That might be the person whose name is going on what you write, or it might be a person in charge of corporate communications who is managing the project. Get as close to that person as possible, and figure out what their main goals are. Chance are, if you make them happy, they can manage everybody else’s objections for you. (If there is no alpha dog and you’re in charge of attempting to keep conflicting people happy without any power of your own, there is pain in your future.)

- Settle and document your plans in a collaborative way. Larger projects like books need a vision to get started. Brainstorm that vision with the whole team and settle the big idea and the table of contents at that time. This not only gets everyone on board with your plan, it helps you observe their interactions and become familiar the roles everyone is playing on the project.

- Iterate on a pilot piece first. If you’re working on a book, this might be Chapter 1. Be prepared that whatever piece you produce first, it’s likely to generate contradictory reactions from members of the team. But this is your chance to revise it a couple of times until you can satisfy everyone, and then use that experience to inform what you do in subsequent parts of the assignment.

- Identify the strengths of the various participants. Maybe one team member has a wealth of case studies to call on. Another might be really good with words and catchy slogans. Yet another might excel at data collection and analysis. Once you figure out who can help you with what, you’re in a good position to tap into those resources as needed to prepare the content you’re working on.

- Choose a tool that allows people to see each others’ comments. I have generally used Google Docs for this purpose; even though its markup features are inferior to Microsoft Word, it’s great at allowing people to see and comment on each others’ edits. It’s possible to set up Word to allow this kind of collaborative editing as well, although it may require you to become a certified participant in your client’s corporate environment. Either way, this type of setup prevents the impossible situation where you get contradictory edits submitted in multiple separate versions of the document file. (Clients who insist on scrawling on paper rather than electronic edits are already a problem, but if you have to manage multiple red-inked printouts from several client participants, you may be better off resigning from the project right now.)

- Manage versions and deadlines rigorously. If edits come in at random times on random file versions, you’ll go bonkers. Instead, draft a version that’s as solid as you can make it, send it to everyone at once, request edits by a specific deadline, and then wait, resisting the urge to tinker with the draft while it’s being reviewed. If your clients adhere to the deadline, you’ll be able to manage their reviews. If they’re chronically late, you need to explain in more detail how the missed review deadlines make it impossible for you to manage the process efficiently and impair the quality of the end result.

- Try to find the “higher truth.” Good writers can look at several possibly contradictory critiques and identify the basic issue that is causing the conflict. Great writers can take that knowledge and turn it into a deeper or more fundamental level of insight. If you can make everyone happy with a more elegant presentation, you won’t just satisfy the clients, you’ll also help readers of varying perspectives to embrace the ideas you’re writing about.

- Resist the urge to charge by the hour. One way to deal with inefficient client processes is to charge extra for the time it takes you to untangle their issues in your writing process. Sure, you’ll get paid for your time, but what writer wants to be paid for managing conflicts? Better to set a single price for the job, and then remind the participants that, to meet that price, you’ll need them to embrace a disciplined process. This positions you, not as an hourly freelance “resource,” but as a visionary writing leader, a role that helps you justify higher hourly rates in the long run.

If your clients are at all manageable, these strategies will work with them. You’ll end up with a document that makes everyone happy (or at least, not unhappy). And you’ll be able to be proud of the result and the reasonable process used to create it.

Have you ever used a RACI matrix for this purpose? Just curious.

Seems like overkill. I guess I’m just used to doing things more intuitively. I think my clients would rebel at a formal RACI approach.

A common scenario looks like this:

Reviewer 1 says, “Arrange these chronologically, from newest to oldest.”

Reviewer 2 says, “Arrange these alphabetically by type; within a type, arrange them by value, from lowest to highest.”

Reviewer 3 says, “Arrange these by value, from highest to lowest.”

Sometimes I’ve prepared it every which way so the reviewers can judge which arrangement will actually work best.

Imagine having that conversation when planning, and resolving it before you actually had to write things.

Do you address issues such as reviewing in your contracts? If you sense they’re going to be a real problem, would you just turn the job down? And a more general question – in ghostwriting jobs who has the final say in what is printed – the person paying the bill?

You could put the part about electronic reviews vs scrawling on paper in a contract. But it’s hard to enforce reviewing methods via contract. Instead, I generally address it via an early discussion, before the job is committed. If you sense that reviewing will be a problem, you could either turn down the job or shift to hourly so you get paid for the hassle. In ghostwriting, as in most freelance work, the client is responsible for the final content. But clients generally appreciate me tracking the final changes, so I’ve never seen something get printed that was different from what I would have approved.