How the reviewer squeeze spawns creativity: thesis, antithesis, synthesis

Every writer whose work is subject to review — by editors, clients, or anyone — has experienced the phenomenon of receiving contradictory reviews. This creates great angst, because you can’t please everyone.

For example:

- You’re a ghostwriter working for two coauthors, your clients. Client one says, “You need to explain this concept in more detail.” Client two says “This is wrong and must be removed.”

- You’re writing a strategy memo. The CTO says “Explain the cost of these elements.” Your boss says “Do not spend time estimating budgets.”

- You’re writing a case study in a business book, for inclusion in a book proposal. The agent says, “Include the outcome at the top of the case study, to make it seem more relevant.” Your editor says, “Do not include the outcome at the top of the case study, it destroys the dramatic tension.”

This happens so often it needs a name. Call it the reviewer squeeze: when you’re caught between people in authority whose needs contradict each other.

The reviewer squeeze is your creative opportunity

When this happens to you, your instinct may be to hide in a hole, because the reviewer squeeze seems dangerous and inescapable. When Mom and Dad are fighting, what are you supposed to do?

In fact, it is your opportunity to become a better writer and create powerful new content.

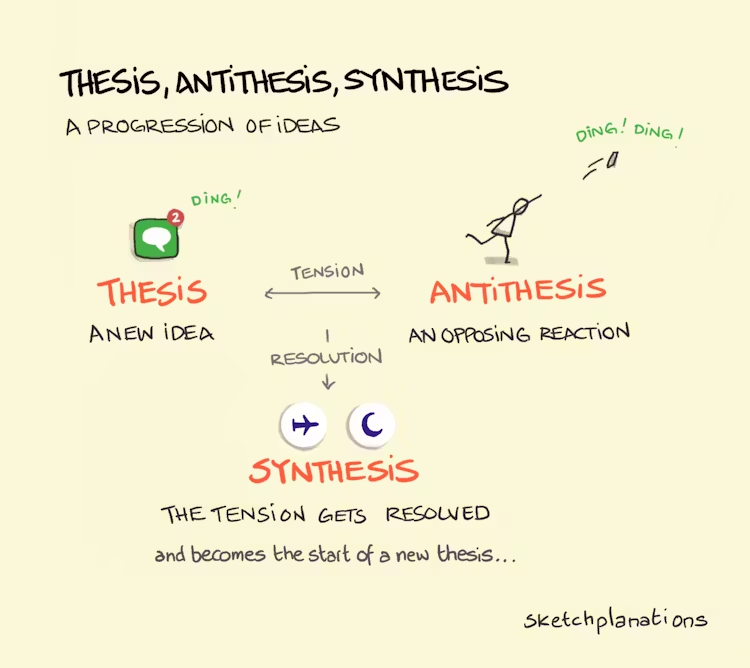

At this juncture I want to refer to the principle of the dialectic originated by the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte, and sometimes attributed to Hegel (don’t worry, I have no knowledge of philosophy at all so I won’t linger long on this concept). As I (poorly) understand it, the dialectic includes the concept that there is a thesis, the thesis has weaknesses that give rise to an antithesis, and this then leads to a philosophical synthesis that represents a higher truth encompassing the thesis and its antithesis.

Whew. Well, if you’re a writer, that must sound familiar. Your job is take the apparently competing comments (thesis and antithesis) and creatively imagine a synthesis that reveals a higher truth about both.

To do this, you must ask yourself why these reviewers are saying what they are saying, and what you could reveal what they would all find enlightening.

If reviewer A wants more detail on a topic and reviewer B wants the topic deleted, then the explanation of the topic is clearly not working. Is there a more fundamental, simpler concept that you could explain that would briefly and clearly satisfy both reviewers?

If two reviewers disagree about whether a topic like cost should be included, why do they disagree? What is it about costs that’s a pain point in the organization? Explain that costs are a pain point and what it would take to get a clearer idea of what those costs would be.

If giving the outcome of a case study ruins the tension, how else could you explain the importance of the case study? Is there a different way to grab the reader’s attention?

Essential in these discussions is a fundamental principle:

- Your job as a writer is not to follow reviewers’ instructions. (You are not a stenographer.) Your job is to understand the problems they cite and generate a creative solution.

- Contradictory opinions are often a clue that there’s a disconnect at a higher level. Probe that. Call it out. Resolve it.

- Synthesis is creative. It represents real progress. It’s why criticism is so valuable — it pushes us to make something not just better, but more fundamentally valuable.

Next time you’re in hell trying to resolve reviews that don’t agree, recognize that you have been presented a rare opportunity. Don’t hide from it. Use it to create something new and powerful.