How much is brevity worth? If you’re Axios, $525 million.

Online news provider Axios just accepted Cox Enterprises’ acquisition offer worth $525 million.

Where did the value in Axios come from? Brevity.

Axios articles are short and pointed

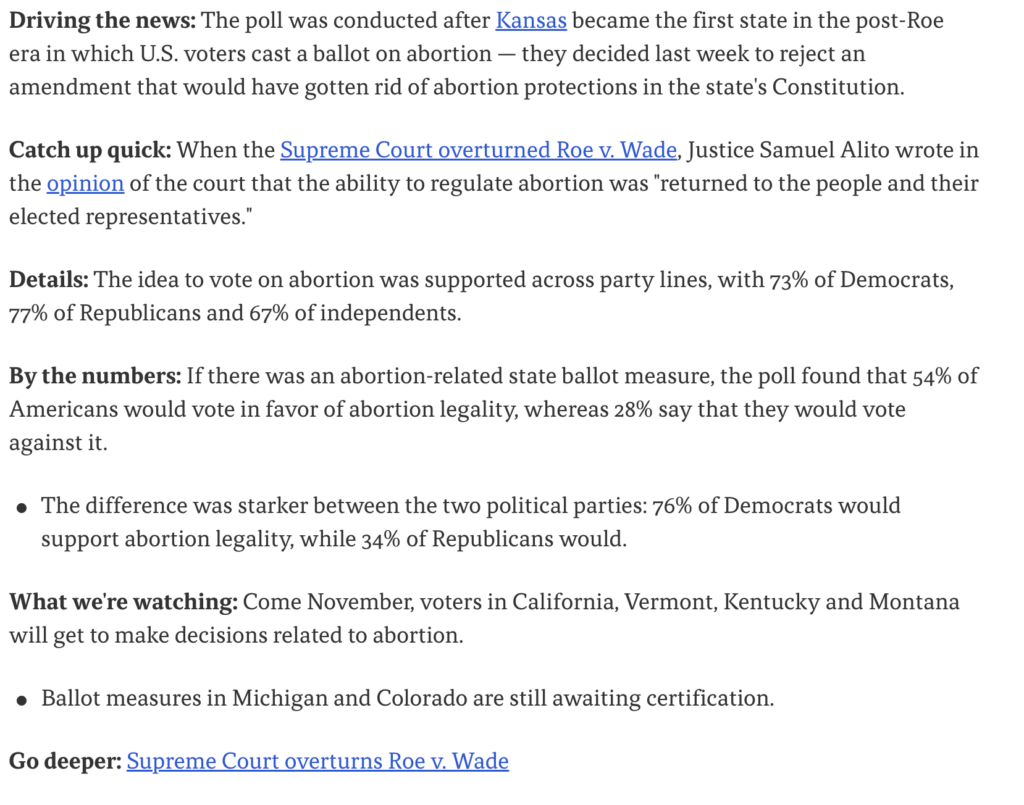

Below is a screen capture of a typical Axios article. The word count, including the headline, the byline, and the photo caption, is 247 words.

What is “Smart Brevity?”

Axios’ trademark (literally) is “Smart Brevity.” Its mission is “Axios gets you smarter, faster on what matters.”

Its five guiding principles are “Audience first; Elegant efficiency; Smart, always; No BS for sale; and Excellence, always.

While I admire the Audience first, No BS (!), and Excellence parts, the differentiation depends on the site’s “Elegant efficiency” and “Smart, always.” Specifically, Axios says:

Our audience is smart already but they are always hungry to get smarter, faster. We resist traffic-based assumptions to dumb things down, and focus our efforts on pinpointing the reason the news matters to you.

- Your time is valuable, so we strive to sort through all of the noise to bring you substantive and meaningful content that is truly worthy of your time.

Take a close look at the article above. You don’t communicate the gist of a news item in less than 250 words without a very rigorous method.

The lede tells you exactly what is going on: 70% of the respondents to a poll want to vote on the legality of abortion, as voters did in Kansas.

Then you get the background and the context — “Driving the news” — and a few details that make sense, about how the responses differed by political affiliation.

Every paragraph other than the lede is either a bullet or includes a bolded heading to tell you what is going on. Interestingly, Axios feels free to violate the standard principle that you need at least two bullets in a bulleted list; they use bullets to show detail under a bolded paragraph heading.

Other key features of this method of exposition include:

- Short sentences. There are no long sentences or paragraphs with lots of clauses to untangle.

- Few weasel words. There are no uses of “likely,” “mostly,” “very,” or other vague qualifiers or intensifiers. Instead of weasel words, there are numbers and facts.

- Let links do the work. Axios is exclusively an online publication. It works because the writers know the news is an ongoing set of interconnected stories. They use links to help you get context if you need to know more, such as their pieces on the Supreme Court decision or on the Kansas vote.

- No cleverness. No subtlety. The writers are not showing off. They are just telling you what happened. There’s not a hint of bias, either — it literally is “We report, you decide,” to quote Fox News’ former slogan.

Is this really the only way to report the news?

Obviously not. “Story-based” journalistic articles still dominate traditional news, and opinion-laden rehashes from outlets on all sides of the political divide also generate plenty of traffic.

And you’d certainly have a point if you described this type of journalism as “oversimplified.” Keep in mind, however, that Axios operates in an environment where there are thousands of other news sources. If you want more detail, it’s certainly on offer (and Axios has probably linked to it). If you want the gist of the story quickly, Axios is there to give it to you.

Because people are in a hurry and reading news on mobile devices, there is a definite market for brevity. Axios has seized it. Their assets — both the method and the traffic — are worth over half a billion dollars to Cox, a company that has mostly divested the rest of its news assets.

If you are regularly communicating factual content, you could do worse than to copy Axios’ practices. At the very least, consider creating executive summaries that focus on short, direct, factual bullets to tell the story. Can you sum up the key points in 250 or 300 words, using links to refer to additional context and details?

The very act of trying to write this way will change how you think about content. It will focus you on getting to the point.

You can lament the short attention spans of today’s readers. Or you can acknowledge the reality and embrace pithiness and brevity to punch through the noise.

It may not be worth $525 million to you. Even so, it’s still worth doing. Because your readers, like Axios’, are flooded with information and pretty damn busy.

I admire the Axios approach. I worry about its sustainability. There’s value in reaching today’s busy readers. Short-form information serves that purpose, plus it adds hyperlinks for those who want to know more. There are dangers to consider:

1. Axios’ brevity is akin to what I like to call “meme journalism.” It doesn’t dig deep, so it relies on links. To fairly cover topics, those links require trusted, objective sources. In today’s politically divided culture, it’s hard to find a source that people can agree on.

2. Many good news sites are protected by paywalls. I pay to subscribe to a couple of news sites, but I can’t afford (or justify) every paywall. I’m sure the average short attention span reader won’t be spending the time and money either.

3. Short-form vs. ultra short-form. What happens when Axios’ data reveals that people aren’t reading to the end of their 250-word articles? Do they cut them to 100 words? And, if people don’t read those, what next… 50 words? At what point are you no longer a relevant stop for an informed public?

As I wrote off the top, I admire the approach. USA Today tried it back in the 1980s with short, news-nugget articles. They eventually needed to expand content to add depth for readers.

Another thought about today’s post:

You suggest Axios uses short sentences. They use one-sentence paragraphs. Many of their sentences are very long. In the example you provided, the longest sentence weighs in at 47 words — a large percentage of the 250-word size of the article. Yes, the shortest sentence was 10 words, but it was an outlier.