How fast will AI replace the Web for decision-making? And what does that mean for authors?

How do people find answers to questions?

For decades, the standard paradigm for decision-making revolved around web sites, links, search (and SEO), content marketing, and social sharing. Whether the question was “How can prepare for a job interview” or “What’s the right organizational strategy for a transnational company?” the answer started with a web search.

AI threatens to wipe that all away and replace it. Many searches now start with an LLM like ChatGPT.

So, is the web dead? And for authors in particular, what does that mean?

The Web will live on

There is absolutely no doubt that the rise of AI is already having a dramatic impact on consumer and business behavior. Among many other effects, there is the rapid adoption of ChatGPT, its dramatization in TV commercials and popular media, significant shifts in corporate investments in technology, a transformation in software coding by machines rather than humans, and small but notable decreases in web traffic from search engines vs. web traffic from LLMs.

AI’s impact itself is protean, having in just a few years morphed from clunky prose to hallucination-filled answers that lacked sources to LLMs that can document their reasoning to agentic AI in the hands of users. And it’s pervasive. Every productivity application, from Google Search to Microsoft Office to Adobe Acrobat, now includes AI features, and devices from phones to PCs differentiate on their AI features, promoted with national advertising campaigns.

But as with all pundit pronouncements that x or y “is dead,” reports of the death of the web are greatly exaggerated.

Consider five patterns that are moderating the shift:

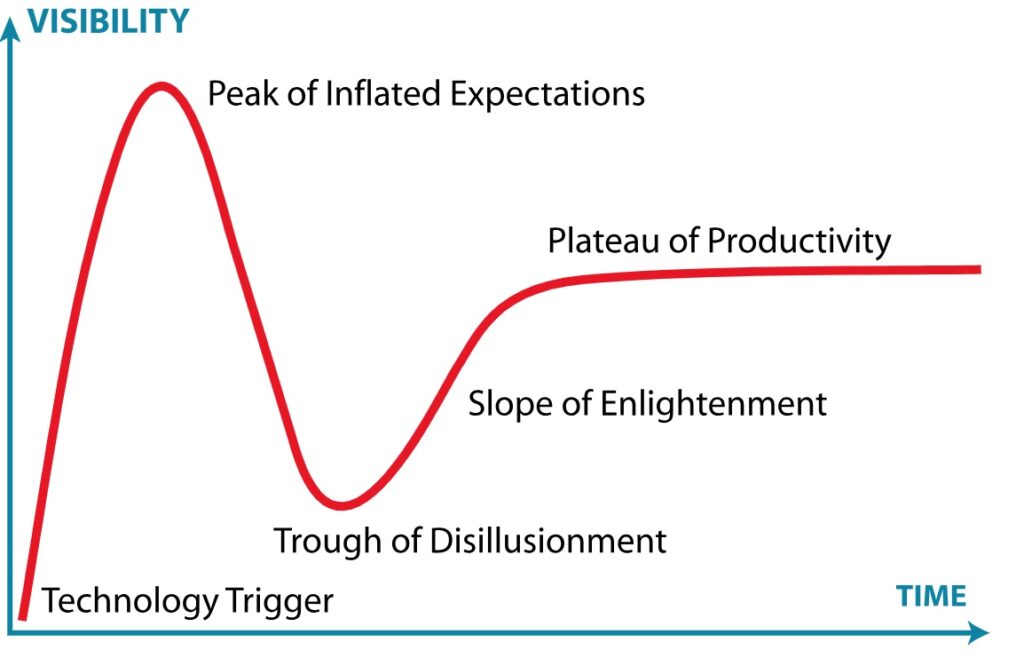

1 The Hype Cycle

We are at the very peak of inflated expectations for AI in the Gartner Hype cycle, which has proven to be accurate for all sorts of tech trends. A backlash is coming.

2 Amara’s Law

Amara’s law, which I’ve seen verified over and over in technology shifts, says:

We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.

So we’re probably overestimating the impact of AI in the short term.

3 The persistence of the old

Based on my long experience observing technology trends, the old things tend to last much longer than people estimate when they’re embracing excitement about the new. Vinyl records persisted years into the shift to CDs and continue to be popular. More than 15 years after Hulu and Netflix launched streaming, 50% of TV viewing is still on broadcast and TV channels. The New York Times and Wall Street Journal still print newspapers 30 years after the birth of the web. While venture capitalists, journalists, and thought leaders naturally embrace the new and innovative, predictions of the “death” of old technology almost always take much longer than analysts and pundits predict. (If you want to get quoted and listened to, it’s hard to do that by saying “Yeah, the old stuff is going to last a while.”)

4 Uncertain timing

While predicting the shape of the new world is quite difficult, predicting the timing of the shift is virtually impossible. My 1995 prediction for the amount of money that would be generated by Web advertising in 2000 was too low by a factor of four. But analysts who predicted the shift of TV to streaming overestimated the timing of the shift by a decade.

5 The new is always built on a foundation of the old

New tech is always rooted in and dependent on the old. Streaming TV production is done by the same studios that created broadcast TV. Social media spreads news that’s generated by old-world media companies like The New York Times and Fox. When AOL merged with Time Warner, people believed AOL was the valuable property, but it was Time Warner (especially HBO) whose value persisted. And remember, the source material for AI is the web and books. If the web instantly ceased to exist, AI would have no training data. Even now, AI-powered searches include links, which are often essential to verify the correctness and source of the information it generates. AI cannot generate news, collect data, or reflect human emotion (it has no wit, and its sense of humor is lousy). And there is the copyright issue. There will be an accommodation between old and new — a profound shift, to be clear, but AI tools stand on a foundation of existing technology and media.

Taking all that into account, here are my predictions for the future:

- AI will radically and profoundly change human behavior and economic models for content and commerce in the decades to come.

- The exact shape of that future is murky. We can see early indicators, but assuming that the future will be similar to the present — or to the current early uses of AI — is a mistake. Anyone who says they know the final form of how people and corporations will be acting as the AI shift matures is probably wrong.

- Even if we could somewhat predict that future, predicting the timing of the future is impossible. The smartest analysts are always wrong about the timing.

- The web, major news outlets, broadcasters, and books will still have life for a long time, possibly a decade. Their form may change, but they won’t disappear in a puff of smoke any time soon.

- If you want to invest venture money or run a conference, talk about AI. If you want a realistic perspective on the mix of media and modalities in the future, watch the evolution carefully and calibrate based on actual economic change.

What this means for authors

I’ve already written about why it’s foolish to write a book on AI right now: it’s in flux, and books take too long.

But ignoring AI is also unwise. It is going to change business strategy profoundly, from marketing to customer experience to management to investing. It’s malpractice to ignore it.

So if you’re writing a business book right now, I have this advice.

- Think about how AI changes the advice in your book from a strategic perspective. That is, don’t the reader how to use ChatGPT to answer questions (because that is going to change). Tell them how AI-based strategies and tools will affect the advice you’re giving. That’s hard, and you could still get it partly wrong, but ignoring AI is an even worse mistake.

- Plan on changes to your marketing. Based on the analysis I cited above, your existing book marketing strategy will still have life in it. That means the things you’re doing now — maintaining a book site, creating content on LinkedIn, making a podcast, posting on Instagram or TikTok, sharing an email newsletter or Substack, or using a publicist to pursue press quotes and bylined articles — are still worth doing. You could also consider investing in AI creations like a chatbot, but it’s not clear to me at this point what the right AI marketing strategy will be. So keep doing what you’re doing, and carefully observe changes in the way everything, books included, is marketed.

- Do not change the marketing plan in your book proposal. Publishers are not impressed by your future-oriented marketing plans. Even though the world will be different two years from now when your book comes out, they are not ready to bet on whatever new way of marketing you may be conceiving. So while the content of your book proposal should address AI, the marketing plan in the proposal shouldn’t. It’s fine to be visionary. But visionary marketing plans don’t impress hard-nosed publishers.

When I first saw stories about generative AI, I predicted that it would eventually add its own output to its inputs. Whatever quality it reached by then would become its plateau. That seems to be happening, and the quality is still very low.

The implications for content are simple and sad: More and more of what we see online will be prompt-generated (not written) by people who don’t know the difference between brilliance and boilerplate.

Thanks to AI in its current form, the web is becoming a strip mall of national franchises on a treeless road in a second-ring suburb.