From mess to book: fast, good, or cheap, pick (at most) one

I’ve seen a lot of messes that were supposed to become books. I learned that fixing messes is neither cheap nor fast, and the results are rarely great. A mess before you start writing is manageable; afterwards, not so much.

What is a mess?

Authors that build books haphazardly create messes.

What is a mess? It’s a collection of partially written, partially edited bits and pieces, random research tidbits, scribbled graphic sketches, PowerPoint presentations, link collections, and 3 a.m. eurekas that didn’t seem nearly as promising in the morning.

In other words, it’s what you end up with if you don’t follow a plan to build your book.

The author faced with a mess has two choices.

They can gamely work their way through the bits and pieces and try to assemble them into something that makes sense. The best way to do this is to deconstruct everything in what I call the sticky-note method, and then attempt to reassemble it. It’s a huge job, and it defeats many an author.

Or they can call an editor, like me, and say “Can you make something out of this?”

Editing messes is slow and expensive, and it generates barely adequate results

I’ve been asked to be the fixer for books that were messes multiple times. Here’s what I’ve learned.

It’s time-consuming, because the editor needs to digest large amounts of disorganized information that they’re initially unfamiliar with. (If a mess is confusing to you, the author, imagine how confusing it is to someone encountering it for the first time.)

It’s expensive, because people who have the skills to make sense of a mess like this are highly skilled and experienced, and such people are well paid. Order of magnitude, you’re talking tens of thousands of dollars.

And the results are disappointing. Messes have gaps that you can’t see until you untangle them. Messes have inconsistent terminology and hard-to-find frameworks. It’s tough to see what the hierarchy of ideas in a mess is. It’s really hard to keep track of what’s original and what’s based on other people’s research.

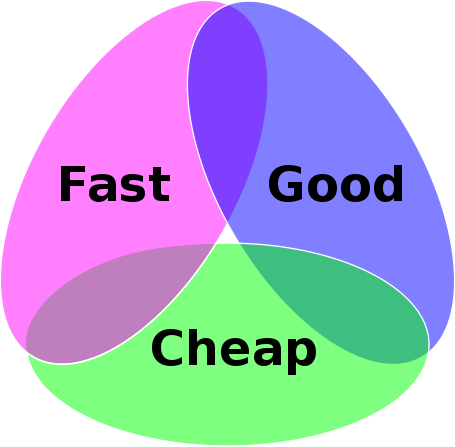

You’ve likely heard the saying “Fast, good, cheap: pick two.” But my experience with projects like this is you’d be lucky to pick even one. If it’s fast, it’s going to be expensive and deliver a disappointing result. If it’s cheap, it’s going to be time-consuming and generate crap. And even if you’re willing to go slow and pay a lot, the results are likely to be just okay, not great.

In the cases where I worked on projects like this, I got paid plenty over a period of months. The books went from unpublishable messes to reasonably coherent and publishable. But they sure didn’t sparkle.

In a normal book project, there comes a point where the book is complete and you begin to see places where you can go from good to great, hitting on newly discovered themes or adding little touches of brilliance here and there. That doesn’t happen when you’re processing a mess. It’s so much effort to get it from mess to acceptable and publishable that no one has the energy to go the next step, from coherent to good or great.

Manage your messes at the start, not at the end

I recently did a ghostwriting project that began as a mess. There was a huge amount of varied source material, mostly slideware, including some gaps that needed to be filled in with research and case studies. The difference was, this was at the start of the project, not the end.

I worked with the authors on a solid idea and a rational way to organize the chapters. I beavered through the source material and interviews with authors to create chapters that made sense. It was a lot of costly work, but the result was a very good book, because we worked together to organize and plan how to process the mess before I started writing.

All projects that require organizing masses of content are messy. But if you plan where you’re going before you write, you can tame that mess and get a great result. If you write first and organize later, you’re in for a world of pain.

Chuckling: “All projects that require organizing masses of content are messy.”

This is the stage I’m battling to write the third volume in my mainstream FICTION trilogy. A project this complicated – a half-million words and over 64 named characters – cannot be left to random writing. And a final trilogy volume requires both rising complications and an ending worthy of the project.

The planning is essential. The first two volumes were carefully created in great detail before writing – but software and hardware changes are forcing me to redesign a lot of the process.

And I know exactly where I’m going.

I can’t imagine mastering the amount of relevant material in any other way, but it is still daunting.