Could the five-paragraph essay be the reason we’ve forgotten how to think?

David Labaree published a devastating takedown of the five-paragraph essay, that pernicious container that’s corrupting the teaching of writing everywhere. He’s made me wonder about my own rules and advice for writers. In my mind, writing and thinking are two sides of the same process. Separate the two, and thinking ceases to be important, which is a tragic failure.

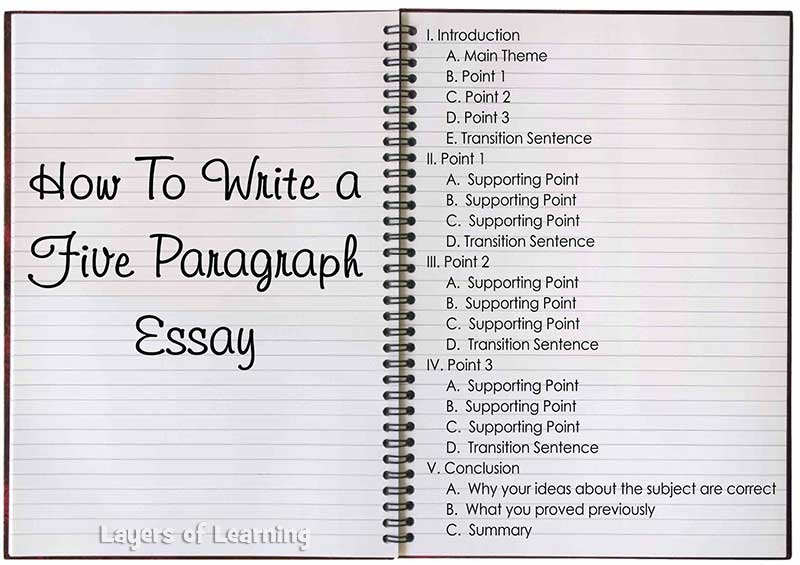

Labaree explains how the five-paragraph essay has corrupted the teaching of writing

Labaree’s piece, published in Aeon, is expertly reasoned, thoughtful, and convincing. As he argues:

Schools and colleges in the United States are adept at teaching students how to write by the numbers. The idea is to make writing easy by eliminating the messy part – making meaning – and focusing effort on reproducing a formal structure. As a result, the act of writing turns from moulding a lump of clay into a unique form to filling a set of jars that are already fired. Not only are the jars unyielding to the touch, but even their number and order are fixed. There are five of them, which, according to the recipe, need to be filled in precise order. Don’t stir. Repeat.

So let’s explore the form and function of this model of writing, considering both the functions it serves and the damage it does. I trace its roots to a series of formalisms that dominate US education at all levels. The foundation is the five-paragraph essay, a form that is chillingly familiar to anyone who has attended high school in the US. In college, the model expands into the five-section research paper. Then in graduate school comes the five-chapter doctoral dissertation. Same jars, same order. By the time the doctoral student becomes a professor, the pattern is set. The Rule of Five is thoroughly fixed in muscle memory, and the scholar is on track to produce a string of journal articles that follow from it. . . .

The focus on form: content is optional. The comfortingly repetitive structure: here’s what I’m going to say, here I am saying it, and here’s what I just said. The utility for everyone involved: expectations are so clear and so low that every writer can meet them, which means that both teachers and students can succeed without breaking a sweat – a win-win situation if ever there was one. The only thing missing is meaning. . . .

The point is that learning to write is extraordinarily difficult, and teaching people how to write is just as hard. Writers need to figure out what they want to say, put it into a series of sentences whose syntax conveys this meaning, arrange those sentences into paragraphs whose syntax carries the idea forward, and organise paragraphs into a structure that captures the argument as a whole. That’s not easy. It’s also not elementary. [Stanley] Fish distils the message into a single paradoxical commandment for writers: ‘You shall tie yourself to forms and the forms shall set you free.’ The five-paragraph essay format is an effort to provide a framework for accomplishing all this.

The issue is this: as so often happens in subjects that are taught in school, the template designed as a means toward attaining some important end turns into an end in itself. As a consequence, form trumps meaning. . . .

Something similar happens with the five-paragraph essay. The form becomes the product. Teachers teach the format as a tool; students use the tool to create five paragraphs that reflect the tool; teachers grade the papers on their degree of alignment with the tool. The form helps students to reproduce the form and get graded on this form. Content, meaning, style, originality and other such values are extraneous – nice but not necessary.

Young writers fill the jars. Teachers grade them on their skills at jar-filling. When everyone follows the formula, no one has to work very hard. That’s all fine until you have to write in the real world of challenging problems and the need to convince actual people, at which point your jar-filling skills are useless.

As Labaree points out, the actual teaching and learning of how to write are much more labor-intensive. But grappling with these issues forces people to think. Having learned to think, it’s easier to put things into persuasive words. And having struggled to put them into persuasive words, you learn a bit more about how to think. That’s worth a lot more than jar-filling, but it’s harder to grade and demands a smaller class. Those challenges are difficult to reconcile with the economic demands and focus on standardized testing in the average American high school.

Are my writing rules equally bad?

Labaree’s obliteration of the five-paragraph essay is so complete that I became concerned about getting caught in the carnage. My book and this blog are full of rules. Don’t write in the passive voice. Don’t use meaningless qualifiers. Start with title and lede that delivers your meaning. Use bullets. Am I just turning out a collection of writers following a different, but equally corrupting, series of rules?

I don’t think so. First of all, none of my rules are absolutes. There are plenty of good reasons to write in the passive voice, and sometimes the best lede is not a summary. I’ve provided guidelines that I think are helpful; think of them as a set of tools. You can build whatever you want with those tools. I don’t specify structure and I don’t supply templates — you have to think those up on your own. So there’s ample opportunity to think, rather than just to fill jars.

Second, there is a principle behind everything I suggest, The Iron Imperative:

You must treat the reader’s time as more valuable than your own.

This tells you what to do, but not how to do it. It gives you a test you can apply to your writing, but not a formula for writing it. Writers who internalize this need to think harder, not less.

It’s not surprising that I’ve declared my advice helpful rather than pernicious. I’d be interested to know if you agree.

The need for critical thinking

At the root of all of this is a simple question: Can students have ideas, and can they back them up?

In my ideal world of teaching and writing, students start an assignment by trying to have an original idea, which they must write down in a sentence or two. They share the idea with the teacher and the class. Some of these are going to be dumb ideas, but they are going to be original. If the idea is the same as what they have heard somewhere else, it is not original, and does not qualify.

The teacher and the class must challenge each other’s ideas. The students have to learn to get used to criticism of their ideas. I’m sure this goes against some pedagogical principle, but if we taught this in every grade, then by the time the students got to high school, they would have learned to think a bit more clearly.

The job of their writing assignments, then, is to convince us of their ideas. And the job of the teacher is to critique the delivery of those ideas on how convincing it is. The form becomes less important than the quality of the arguments.

My experience of students is that they are capable of an astounding level of originality and energy. (Of course, I dealt mostly with homeschooled students, who are not as infected by the punishing need to fit their thinking into rigid molds like the five-paragraph essay.) A constant stream of ideation and critique molds those students into actual thinkers, rather than jar-fillers.

We are hip deep in a media world filled with alternative facts, false arguments, and flaky reasoning. An electorate in which large segments have forgotten how to think swallows this stuff whole. The only defense is to create students who can think for themselves, know the difference between an idea and a relentlessly defended position, and are ready to become actual thinking adults.

Can we please get started on this?

In the early 1990s, I was taking a graduate class in Technical Journalism. During the second week, our professor was explaining the five W’s.

I raised my hand.

“Yes, Paul?” said the professor.

“What percentage of Pulitzer Prize winners follow this formula?”

My professor grinned. “I get your point, Paul. What I’m teaching is how to write serviceably. It is by no means the way to write superbly.”

I love teachers who love tough questions!

I do agree with this summation, Josh, and I believe the situation is getting worse because of all those “gurus” out there telling people it’s easy to write a book, and they should just ignore everything they learned in school from their English teachers. Simply write five paragraphs for each chapter, ignoring punctuation and grammar because they are unnecessarily restricting. And there’s really no need for an editor — just throw it up on Amazon and you can call yourself an author.

No wonder there’s so much garbage on Amazon!

Throw it up indeed!

This post made me think of Toastmasters. There is a workbook of projects that are skills-building blocks to teach participants the form, purpose, and variety of speeches and presentations. The “rules” (for example: “say what you’re about to say, say it, say what you said”) become a cliche once someone gains experience, but they are a useful default to fall back on if the mind goes blank with stage-fright. There is a segment of every meeting called “Tabletopics” where a speaker is given a random topic to speak on for two minutes with no preparation. It forces the speaker to think. Most people wander up and just start talking conversationally, never realizing the discipline of the form — that it is actually a mini-speech that requires a starting point, a body, and a powerful ending.

Problem: Standardized tests, like the ACT (and state-specific ones like Wisconsin’s WKCE), have an essay portion that considers formulaic writing as a positive attribute. If we want kids to become independent thinkers and creators (and I hope we do), we need to reconsider our love of standardized testing. We need to trust teachers to bring out the individualized best in our students. We need to fund educational creativity, not teaching to the test.

Shocking.

I spent more than twenty-five years teaching literature and writing classes to college undergrads and occasionally grad students. Never once did I ask for a five paragraph essay. I did ask for structure that reflected in its form the ideas presented and the way in which they related to one another. I was,however, fortunate to be included in an extraordinarily enlightened department for most of those years. The one year that I was sent on loan to a neighboring but exceedingly formulaic institution demonstrated with exquisite precision the thought-killing process you describe.

Thank you for the courageous post.

As a marketing/strategy consultant, I am constantly trying to get people to think, by asking questions, and proposing weird ideas to act as discussion starters.

The bane of my life is the template marketing plan, a set of ‘jars’ that are filled without thought, as noted, whose only job is to tick the corporate box of ‘marketing pan complete by….

Just googled ‘marketing plan template’ and got 10 million plus in .015 seconds. At least there is plenty of choice of your brand of intellectual poison.