How to build on ideas without being a ripoff artist

You can write about and extend other people’s ideas. You can come up with your own, independently. But even if you think you thought of it, you’re better off checking first. Because ripoff artists are the worst.

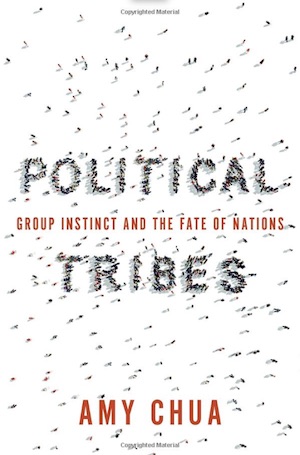

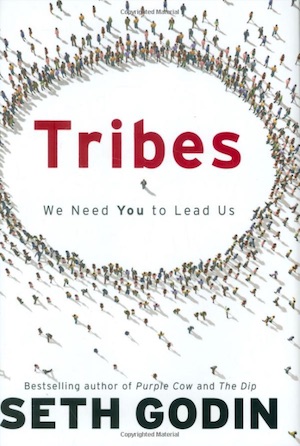

This week, Amy Chua is publishing a new book, called Political Tribes. Here’s the cover, along with the cover of a popular and original book by Seth Godin, called Tribes, published 10 years earlier.

Striking, isn’t it. And Seth’s book is not obscure — it has 609 Amazon reviews, with an average of 4.3 stars. It changed how people think about leadership, virality, and social media. Seth wrote a post called Stolen Ideas discussing the similarity between the two covers and what it might mean for creativity. Here’s what he says:

The paradox of non-fiction book publishing (and I’d stretch it to include popular fiction as well) has two components:

- Authors steal to write.

- And the writing they do gets stolen.

It’s easy to get up in arms about the second, but essential to embrace the first.

It’s true, stealing and building on ideas is how civilization moves forward. Whenever we create, we build upon, crib from, modify, and yes, steal from what came before. Sometimes the new part is highly original, sometimes it’s not, but nobody starts from nothing — the complete matrix of the knowledge we have assimilated is in our heads when we begin.

Do you know the difference between fair use and piracy?

When you use my content, that’s piracy.

When I use your content, that’s fair use.

How to create conscientiously

There is a time when things are ripe for an idea, an image, or a word. Newton and Leibniz came up with calculus at almost the same time. Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace independently conceived of natural selection.

I’ve fallen victim to this myself. I coined the term technographics to describe a segmentation of people according to how they use technology, but I wasn’t the first to say it. I described the fragmentation of the way people access the internet with the term splinternet, but I wasn’t the first to use that term, either. I vividly remember coming up with each term — in the first case, I was discussing it with my boss, Emily Nagle Green, and in the second, I was musing about the problem in the midst of a walk. But that doesn’t make the terms mine. (I’ve linked to Wikipedia articles here since they are relatively objective in describing the various uses of the terms.)

It’s entirely possible that the artist that did Amy Chua’s book cover had never seen Seth Godin’s. But that cover should never have been published. If you search “Tribes” on Google, you’ll find Seth Godin’s Tribes. And once you see that cover, you cannot go forward and publish the art for Political Tribes. I blame the publisher. (Ironically, the two books share the same publisher.)

In a world where Google exists, there is no excuse for not knowing you are ripping someone off.

So here are some rules to live by:

- Create. It’s what life is about.

- Learn. Starting from scratch is for idiots. Become an expert in whatever you seek to do. Find out who else is doing it and what they are saying. Find people you agree with and those you don’t. But be aware of what’s out there.

- Build. Figure out where you can add value and ideas. Start from what exists and create something new and original from it.

- Cite. When you know you are using someone’s idea, give them credit. Footnotes are old-school, but fine. Links are fine, too. Quotes with appropriate citations are good as well.

- Dig. It’s a little more work, but don’t just cite the first thing you find. See where they got their ideas. Go back to the originator of the idea.

- Connect. Call or email the person whose work you’re citing. Find out what they think. (Yes, I’ve been in contact with Seth about this topic.)

- Search. Even if you think you are original, do a Web search. Do an image search. It’s not just to find who else already said it. It’s so you can make sure you will appear higher in searches — so you can be sure you can own your own ideas on Google. And if somebody else came up with it first — even if you think you thought of it on your own — give them credit.

Nice insights into a common writing issue; I teach college writing and I will have my students read this.

That the two books share the same publisher makes their extremely similar covers an even more embarrassing situation. Curious, who is responsible for a book’s cover design? Clearly, the person (or team) failed to do even the most rudimentary research on cover design.

In a normal publishing relationship, the publisher hires an freelance designer or works with an in-house designer to generate the cover design. The author typically has the ability to accept, reject, or provide feedback.

Hi! This is Amy Chua. My daughter just sent me this link, and I’m horrified! I had no idea that another book called Tribes had such a similar cover! I DID know (because some friends alerted me) that some other books had similar design conceits, like Clay Shirky’s Cognitive Surplus and Tina Rosenberg’s Join The Club. For that reason, i initially opposed the design, but after much discussion. But I never saw the Tribes cover (although I am a fan of Seth’s work), and i don’t think I would have gone forward had I seen it. I’ll try to figure out how to reach Seth — and many thanks for your blog.