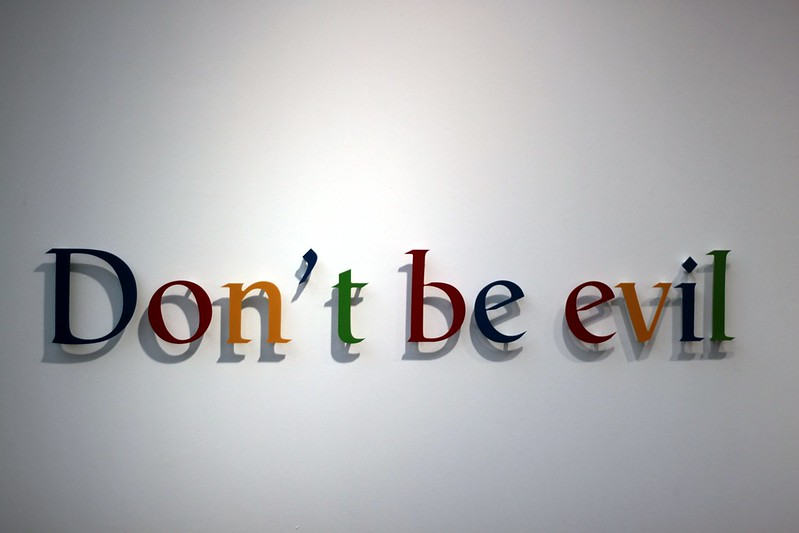

Don’t be evil (for freelancers and employees)

Google used to embrace the principle “Don’t be evil.” Even if that’s no longer central to their way of doing business, it should be to yours.

As a freelancer, you might be asked to do anything. And as an employee, you might face difficult ethical choices. In the back of your mind is a thing called a conscience. It should be present at all times when you are working (and it tends to get noisy and annoying if you ignore it).

Don’t agree to do any of these things:

- Lie to colleagues. If your work requires deceiving your fellow workers, you shouldn’t do it.

- Lie in published material. Yes, freelance writers get asked to do this all the time.

- Lie to customers.

- Design systems that deceive people, for example, into buying things they didn’t realize they were agreeing to.

- Falsify business records about, for example, the hours you work or what paymetns you made and why. (Apparently, somebody recently got in trouble for this.)

- Change previously published or logged work to make it seem different from what actually happened at the time.

- Steal others’ text, images, or video and represent them as your own.

- Steal others’ ideas and represent them as your own.

- Create content designed to get people to hate each other.

- Promote toxic ideas, such as racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, or any other content that suggests that one type of people are superior to another.

- Write, publish, or present something you vehemently disagree with and don’t wish to be associated with. (As an analyst, I turned down client engagements with companies that were behaving in ways I considered evil and offensive.)

- Evade taxes or other laws.

- Hack into systems of organizations. (There is, I suppose, an argument to be made for white hat hacking, but doing it for personal or corporate gain is always a problem.)

- Intentionally skew analysis of data to promote a point of view.

- Intentionally ignore available and reliable information that contradicts a point of view you are promoting.

- Intentionally draw conclusions not supported (or not sufficiently supported) by data.

- Act in ways that advantage yourself or pay you more to the detriment of your organization or client.

- Bully weaker people.

- Reveal information or otherwise violate agreements, including NDAs, that you have signed.

This is of necessity an incomplete list; people keep coming up with new ways to be unethical. But there’s a simple rule of thumb. If everyone read about what you were doing on the front page of the New York Times, would you be okay with that? If not, you probably shouldn’t be doing it.

When I came up with a very clever but ethically shady idea in a previous job, my boss cited the “mom test:” “Would you be okay if your mom knew you were doing this?” I wouldn’t. So I didn’t do it.

We are all evil

It is very easy for me to write all this stuff down. It is not so easy to always follow these rules.

Freelancers who need money will sometimes feel that feeding their families requires them to do something ethically questionable. Or you may be well into a project when a client suddenly asks you to violate a rule, because “everybody does it.” (This has happened to me, when I found out an editing client was writing about experiences that hadn’t actually happened.)

When you are an employee, it’s very hard to refuse to perform work that managers have told you is perfectly fine, just because your own moral compass tells you it is wrong. You could lose your job, and most people can’t afford that.

Because of these sorts of conflicts, nearly everyone has had to do something evil in their work. In some cases, we didn’t realize it was evil until later. But if you’ve worked for more than a few years, you’ve probably encountered requests to do evil things, and you probably had to comply.

Here is what you need to know.

First, the evil thing you did will bother you. You’ll lose sleep over it. There is a psychic cost to doing evil, even in small ways.

Second, the only way to maintain your integrity is to stop doing it in the future. If you stop, you’ll feel a little better. If you keep going, you’ll feel a lot worse.

Third, if you keep doing the evil, you will become inured to it. You can wear down your conscience. At that point you have lost your soul, and no job is worth that.

Fourth, companies that do evil things get caught. Your may feel you are contributing to your company’s or client’s success by doing the evil it asks of you, but in the end, you are actually contributing to its downfall.

And finally, there are far more ethical people in the working world than scoundrels. People with integrity will hire you, eventually.

So it’s not just about avoiding doing evil. It’s about saving your soul and doing what’s best for the company in the long run.

Don’t be evil. If you’ve been evil, as we all have from time to time, stop.

Excellent! May we all strive to adhere to these integrity markers!

As you say, we won’t and can’t do it all, all the time, every time. But when we are aware of these principles, it’s easier to gird our loins against those who will whisper sweet temptation in our ears and wave money at our eyes.

And when we do fail, we must own up to it, pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and learn from our error so as not to repeat it. As a young American musician, Eric Stanley, refers to mistakes: “It’s a life lesson, not a life sentence.”

I’ll be quoting you when I get around to writing an article explaining why I will never return to proposal writing.