Contributed op-ed case study (3): Planning and writing

Writing can be easy, provided you prepare properly. I’ll show how that applied to the op-ed I placed in the Boston Globe last Sunday.

Let’s start by talking about two types of writers, planners and pantsers, a concept I borrow from fiction writers.

Planners are the people who map everything out ahead of time, in detail, before they write. Pantsers are the ones who write by the seat of their pants — just seeing where things go.

When it comes to nonfiction, the two types have more in common than you might think. When the pantser just starts typing, they’re basically creating a shitty first draft, one that will require lots of revision. That very rough draft is not all that different from the detailed plan that the planner creates.

The pantser strategy works fine if you’re a good mental planner — that is, you have a rough idea in your head of where you’re going — and if what your writing is neither critically important nor very long. I use it myself for most of my blog posts. But if you’re working on something carefully reasoned, detailed, or long, the pantser strategy may get you into trouble. You’ll spend a lot of time reworking and rewriting that draft into a tightly reasoned argument.

Pantsers also have another problem: writer’s block. They often feel they can’t get started or can’t get going. The reason may be that they don’t have the pieces assembled that they need to start writing. In my experience, planning cures writer’s block.

There was no way I was going to seat-of-the-pants my way through this project. It was time to plan.

Planning a nonfiction essay: the fat outline

As I described yesterday, I did extensive research for the social media op-ed and generated about 10,000 words of notes.

I had a general idea of the thrust of the piece, which would include these points:

- Social media is polarizing America.

- Breaking up social media companies won’t help the problem.

- Regulation needs to bring people’s shattered realities back together.

- There is a justification for such regulation at the FCC, following the precedent of the Fairness Doctrine.

- The best way to implement that regulation is through ad space.

- Showing ads from liberal sources to conservative readers, and vice versa, will knit up the divisions in both the electorate and the media.

With this in mind, I started to create a fat outline. As I describe in my book, a fat outline includes lots of detail about what bits will be in the final piece, and in what order. To create it, I worked my way through my notes, picked out relevant bits and pieces, and arranged them approximately in the order in which they would appear in the final essay.

Here’s the first half of my fat outline. Notice a few things about this. The order matches the sequence of the final essay. It includes links for all the sources. Also, it’s full of grammatical errors and would never be mistaken for a finished piece of writing. Normally, the only people who would see this are you, the writer, and sometimes your editor. The full fat outline was also 5000 words long, twice the target for the essay, so I knew that many of those bits and pieces needed to be shortened, summarized, or cut.

It took about two hours to create the full fat outline. But having created it, I almost felt ready to begin writing.

The question method

To get the structure of the essay clear in my mind, I wrote it out as a series of questions. I put those questions right into my empty draft document. Here’s what I started with:

Social Media Is Destroying America. Here’s How to Fix It.

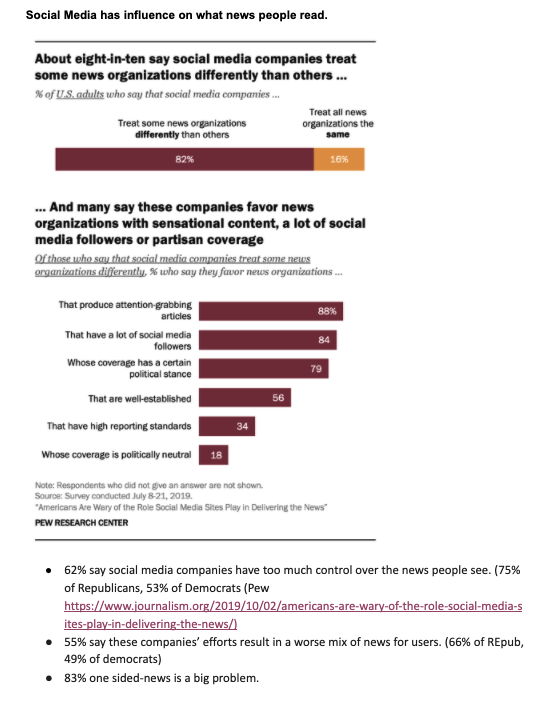

How does social media influence news consumption?

How does it contribute to filter bubbles?

How big is the problem?

Why won’t breaking up the companies fix it?

What is the justification for FCC regulation?

How is this like the Fairness Doctrine in the 60s and 70s?

What is Section 230, and why is cancelling it a bad idea?

How can advertising solve the problem?

What would be the positive effects of this advertising solution?

Having written this, I felt relaxed and in control. I knew exactly where I was going, and what evidence I would be bringing to bear. So, finally, I could start writing.

Writing in flow

I wrote the whole essay in about an hour and three-quarters, in one sitting. It was one of the most pleasurable writing experiences I’d ever had.

Having done the preparation, I conceived of the right title: “Social Media Broke America. Here’s How to Fix It.” And I decide that my lede would come from a famous quote by the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan once said, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts.” But that was before social media. Now thanks to social media, we can each have our own set of facts.

When you are writing in flow, creation is effortless. Your brain is focused on one thing at a time: what is the next sentence? To make this possible, you need to have all the evidence you will cite in front of you, well organized according to how you will use it. And you must have the crystalline structure of the essay clear in your mind. With all the other crap removed from your attention, you can concentrate on solving the problem of writing the essay, one sentence at a time.

In addition to being pleasurable for the writer, an essay written in flow is pleasurable for the reader. Because the sentences connect smoothly, the essay carries the reader along in the argument. And as a result, that reader is more likely to say: “Yeah, that’s exactly right!”

You can read the full 2400-word essay I submitted to the Globe here.

Just after I submitted the essay to the Globe, I sent quotes to the people I’d interviewed so they could verify the accuracy. (I knew there would be time to fix any issues in subsequent drafts.)

I beat my deadline by a couple days. All seemed on track. But as you’ll read tomorrow, the editors had a bunch of changes to request, so there was still lots of work ahead to get this piece published.