Contributed op-ed case study (2): Research

If you’re contributing a piece to a major publication, they will want something new. If it’s new, it probably requires research. Today I’ll share how I do research — and specifically, what I did for the piece I published last week in the Ideas section of the Boston Sunday Globe.

As I described yesterday, I successfully pitched the Globe an idea around social media regulation that would parallel the 1970s era Fairness Doctrine. I also left myself two weeks to do research before writing it. Why do research? Because you can:

- Make yourself smarter by talking to smart people and reviewing smart content.

- Test out your ideas on smart people, to make sure you’re not missing anything.

- Gather quotes and statistics that will bolster the authority in the piece.

All of these are important, and you can conduct them all simultaneously.

Stalking the interview

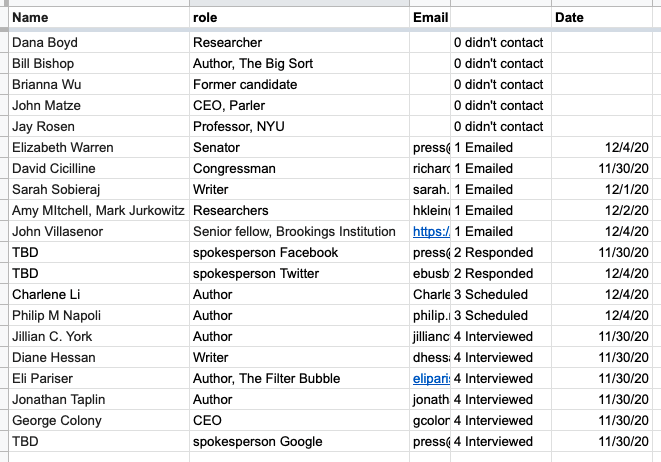

I use a Google sheet to keep track of interviews. Here’s the sheet I created for this project (I’ve hidden most of the email column for privacy reasons.)

Who are these people? Many are authors: Philip Napoli wrote a book on social media regulation, and Charlene Li, Jonathan Taplin, and Eli Pariser wrote books directly on point for this topic. Others are spokespeople for the subjects of the article: Google, Facebook, and Twitter. (It’s always instructive to get opposing viewpoints.) Others are people I identified through an article search. Finally, there are the spokespeople for elected officials from the Globe’s coverage area who had commented on the topic: Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren and Rhode Island US Representative David Cicilline.

In some cases (like Eli Pariser), there was no accessible email, so I had to send in a contact form. In other cases I went through the organization or influencer’s press page to find a way to contact them. This is how I made contacts with Google and Twitter and the members of Congress, for example.

Your pitch email has to be clear and to the point, you must send a separate email to each contact, and you must customize it to the target. For example, here’s the email I sent to author Philip Napoli.

Subject: Would like to interview and quote you in a Boston Globe op-ed

Professor Napoli:

I’m writing a longish op-ed that will appear in the Sunday op-ed section of the Boston Globe in December. The topic is how Facebook and other social networks distorted our view of the world and affected the election. I’ve written several other op-eds for them, you can see the list here.

I’m reading your book “Social Media and the Public Interest” and it’s directly on point. If we could set up 20-30 minutes to talk before Wednesday 9 December, that would allow me to get your perspective into the article. I recognize that you may be in the midst of finals, I’m hoping you can fit this in.

Quickly on me: I wrote a bestselling book on social media in 2008, “Groundswell,” and have written or edited a dozen business books since then.

I hope we can get a chance to talk soon. I’m looking forward to hearing from you. Let me know what times might work — I’ll make it work on my end.

Notice that the “ask” is in the subject line, I describe what I already know about the target, I include a deadline, and I briefly mention my own credentials. Most important: it’s short. Long emails don’t get read.

I track the interviews on the sheet and come back to people who haven’t responded. Because I use numbers to indicate how far I’ve gotten with each contact, it’s easy to sort the sheet based on who has responded and who is in process. I also held off on contacting some who I rated as lesser priorities. My hit rate was about 50%.

Web research

You’ll always find valuable information online. My two main sources are Web searches and articles that appear in my social media feeds. (Because my friends on Facebook and Twitter are interested in the same topics I am, they often post articles that will be helpful to me.)

In this case, a Web search on social media and the fairness doctrine revealed these pieces:

- Lessons for social media from the Fairness Doctrine (This was the article that led me to contact Professor Napoli.)

- Why creating an internet “fairness doctrine” would backfire (This article opposes my point of view, and was a good source for shoring up my counterarguments.)

I also needed statistics about who reads news online and how much it influences them. Searches will find these sorts of documents, but I also know that the Pew Research Institute is an authoritative source on such topics with research that’s not behind a paywall. That’s how I found these sources:

- Americans Who Mainly Get Their News on Social Media Are Less Engaged, Less Knowledgeable (Pew)

- Social Media Fact Sheet (Pew)

Web researchers must be aware that articles that appear at the top of searches are just quoting original research from others. Always go back to the original source. A Pew statistic quoted in a Forbes article is not as useful as a finding the original Pew piece and looking at the context for the statistic. Also, make sure you’re looking at the most up-to-date research. The top Web hit for Pew on these statistics was from 2018, but poking around the Pew site, I found comparable statistics from a piece written in 2020.

Books

I bought books for this project and spent time poring over them. For example, I wanted to ensure I reviewed Eli Pariser’s book The Filter Bubble before speaking with him. And I found Professor Napoli’s book Social Media and the Public Interest to be a gold mine, since it covered regulation of media and social media at a level of detail that made me much better educated on the topic. My conversation with Napoli was far richer given that I’d read most of his book, and I had already identified passages from it that I wanted to quote.

How I organize content

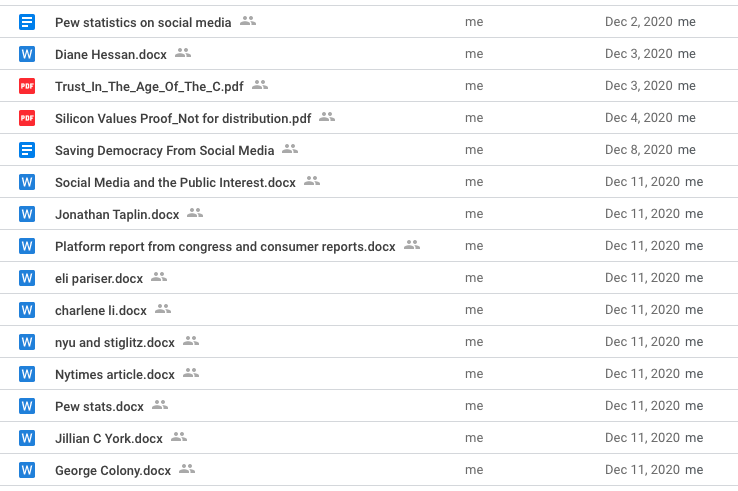

Some writers use tools like Scrivener or Evernote to organize their content notes. I just take notes in Google Docs or Microsoft Word. Here’s how my directory of notes for this project looks:

Notice a few things about this. There are interview notes from contacts like Jonathan Taplin and Diane Hessan. There are source documents, like a proof of an upcoming book that Jillian York shared with me. And there are pieces that include my notes taken directly from online sources. When I use those sources, I am scrupulous about including links for where I got them; when you’re writing, that is essential for keeping the sources straight.

My notes consist of partial transcripts of the conversations as well as nuggets of information from the other sources. For example, here is part of my file for my conversation with Professor Napoli and what I got from his book. The conversation notes are fragmentary and certainly not appropriate for publication — they’re mostly reminders of things I could quote.

From my conversation:

. . . There are rationales and justifications and we could make . . . on what grounds could we justify imposing on the first amendment rights of the platforms.

My argument, idea that these aggregations of user data that are the economic engine for these platforms, are a publicly held resource, just like broadcast spectrum. How it was, broadcasting in particular, related to falsity and disinformation. Thing that’s happened in our regulatory model, we have carved out this space for only certain media to have a strong public interest regulation.

From Prof. Napoli’s book:

Zuckerberg testimony 2018: “We didn’t take a broad enough view of our responsibility, and that was a big mistake.” (p. 4)

Platforms don’t see themselves as tech companies.

No human editorial intervention. So not a media company. Facilitators.

“Algorithms, though automated, classify, filter, and prioritize content based on values internal to the system and the preferences and actions of users. Moreover, engineers, and other company actors must make countless decisions in the design and development of algorithms. Through those decisions and relationships, subjective decisions and biases get encoded into systems, giving rise to algorithmic biases.” (Pp. 12-13)

“. . . these companies operate as news organizations, given the extent to which they are engaged in editorial and gatekeeping decisions related to the flow of information.” (p. 13)

“In combination, filter bubbles and fake news represent perhaps the most challenging and troubling dimensions of how social media platforms and algorithmic curation may be affecting the social media ecosystem.” (p. 81).

Historical Focus on “counterspeech” – more speech is an effective remedy against the dissemination and consumption of false speech. (p. 82)

Justice Louis Brandeis in Whitney v. California: “If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.” (p. 83). Oliver Wendell Holmes: “The ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas—that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.”

The net result of the research

At the end of reading all this material and speaking with all these experts was very helpful in developing my own ideas. I became convinced that my plan to regulate social media was in line with past actions by the FCC. And I conceived and then tested out the idea that the solution could be implemented by advertising, rather than manipulating the algorithms. Several of the experts I spoke with were intrigued by that suggestion, which reassured me that I could make it central to the op-ed.

The other output of all this effort was about 10,000 words of notes that were full of useful nuggets and quotes that could go into the piece. So, two weeks into the project, I was finally ready to write.

I’ll talk about planning and writing in tomorrow’s post.

This is a master class in opinion writing. I plan to share with my students in an upcoming winter 2021 class on writing an op-ed.

Thanks, Josh: you are an educator at heart.