Confessions of a mansplainer

I am a mansplainer. In the hopes of enlightening readers of all genders as they interact in the workplace, I’ll examine how I got that way, why I mansplained, and my path to reform.

First off, let me explain my background, because it matters in this discussion. I was raised in a moderately affluent suburb of Philadelphia; my parents were a college chemistry professor and a well-educated homemaker. They reinforced my desire to succeed academically, and I did. I went to high school and college in the 70s, a time when the sexual revolution had cracked the shell on rigid gender roles, but the idea of women’s equality and accomplishment, while attractive in theory, hadn’t yet made things much easier for accomplished women.

My time in college and graduate school reinforced in me the idea that I had a superior intellect. I was an elite student in a respected field — mathematics. By the time I entered the working world I had a towering ego and sense of superiority, even though as an actual worker I knew nothing at all.

But put the ego aside for a moment.

Teachers and professors shaped my experience in high school and college — I looked up to them, including my father. In graduate school I taught calculus, including a memorable summer in which I taught a class of naval engineering students far older than me. My first boss hired me because she needed a person with a math background who could write clearly about equations and their application, and I rapidly became a resource for others who needed help with those topics. So I learned to lecture.

Writing non-fiction is explaining. As a technical writer and manager, I became a professional explainer. As I look back on my work, I see now that explaining is what I do. I’m good at it, people value it, and it gives me a great deal of satisfaction.

Explainer or mansplainer?

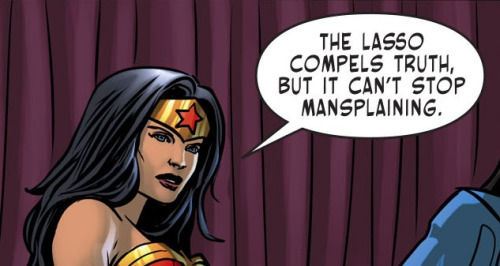

So that all explains why I am an explainer. By why a mansplainer? A mansplainer is a man who continues to explain things to women, even though the women know about those things and may understand them better than the man does. It also implies an element of condescension — that the man acts as if he is of course smarter than the woman to whom he is explaining things. It’s frustrating to be the subject of a lecture when you are smarter than the person lecturing.

In Rebecca Solnit’s formulation, a mansplainer must have a combination of “overconfidence and cluelessness.” To be a mansplainer, you must have the following:

- A feeling that you are smarter than your audience.

- An insensitivity to how the audience is reacting — that is, you miss the cues that you’re being offensive.

- A prejudice that women are less smart than men.

OK, let’s take that apart. My background reinforced in me the feeling that I was smarter. And I was much better at talking than listening. I think that for the first few decades of my career, I was pretty bad at picking up on cues from anyone. So I hit the first two criteria squarely.

I don’t think that I’m prejudiced against women thinkers. I have encountered so many smart women in my career. Dena Brody, my first boss, was someone I instantly admired and hoped to emulate when I became a manager. I also think about women I’ve worked closely with, including Myrna Jacobs (the woman I hired to run the department I built at one startup), Mary Modahl (the VP who hired me at Forrester), Charlene Li (the coauthor of my first book), Kerry Bodine (the coauthor of Outside In, which I edited), and Carrie Fanlo (who rose from entry-level research associate to SVP of Research at Forrester). I am in awe of the skill of these women; I have learned from them and consider my friendship and collaborations with them as some of the highlights of my career. I cannot imagine mansplaining anything to any one of them.

That said, I have to admit I am a product of my time. While things were not quite as bad in the 80s and 90s and 00s as they were in the “Mad Men” era, men at work in those times were prone to considering women, not just as colleagues, but from a sexual perspective. I cannot imagine the challenges of a woman succeeding in an environment where she must deal with that.

The analyst paradigm

I spent 20 years of my life as a Forrester analyst. And I was pretty good at it.

The job of the analyst is to learn as much as possible about a particular field, to study it, to conduct primary research about it, and then to write about it and explain (yes, explain) what is happening and what is going to happen. People pay a lot of money for those insights.

The analyst’s interactions with the rest of the world demand a certain attitude, and if you are a mansplainer, the job will reinforce those tendencies.

Your non-analyst colleagues hold you up to the world as an icon of knowledge and reinforce the idea that you know things that others do not.

Technology vendors large and small brief you with the implicit assumption that winning your approval is crucial to their success. To them, you are an influencer. So they reinforce the idea that your knowledge of the market is superior.

Clients ask you to speak to them about strategy. They assume that your knowledge will help them. They expect you to know everything. To meet their expectations, it helps to act as if you know everything.

The press calls and asks for your opinion, then quotes you in the paper, on the radio, or on television as an expert.

There is no sexism inherent in this, only a feeling of intellectual superiority. While there are more men than women in the corps of analysts, there are plenty of accomplished women analysts as well. And some male analysts are less arrogant than others. But if you’re already arrogant, this job is going to reinforce that.

Analysts also need to listen — you’re not going to learn much about a changing market unless you can listen. They also meet with some impressive people. In my time as an analyst I interacted with Bill Gates, Mark Andreessen, Mark Zuckerberg, and the CEOs or Presidents of NBC, ABC, CBS, News Corp., Discovery, and many other Fortune 500 companies. You don’t get far being arrogant with people like that. Even so, in most interactions, you are supposed to be the smart one, and you’d better act like it.

What I’ve learned since starting on my own

I am no longer a widely respected analyst. I am a small businessman and author of a moderately selling book. Behaving like I know everything is no longer an option.

I am still an explainer, just as I was when I was teaching calculus. But I see things differently.

For one thing, nobody is going to hire you unless you listen. So I have gotten much better at picking up cues, listening, and respecting what other people are doing and what they know. If you want to write a book and I want to help you, I need to respect the knowledge you have in your area of expertise. My knowledge is about writing and publishing, but that’s worth nothing without your ideas.

It was heady being at the top of all that respect and adulation, but I’m enjoying this a lot more. I’m having more equal relationships with people and enjoying listening to them. My ego is now in a normal-sized box. So I’m an explainer, but not from a position of superiority. To do my job, I need a lot more empathy about what other writers are going through.

I’ve learned a little about gender in the workplace. My editor (a woman) and her boss (a woman) encouraged me to look into the challenges of women writing in the workplace, and I wrote about that on the blog and in my book. I’m quite insecure and uncomfortable talking about it, because I feel like a man mansplaining the challenges of women in the workplace, but it’s part of the challenge of writing, and therefore part of what I speak about. I’m still learning.

So I guess I am a recovering mansplainer.

To all the women whose ideas I didn’t listen to sufficiently . . . I apologize. It has taken many decades, but I think I am listening better and mansplaining less now.

Advice for mansplainers and their victims

If you are a man reading this — especially if you are a smart and accomplished man — consider that you may be a mansplainer.

If you are open to change, make a vow to listen more and talk less when you are in conversation with a woman or in a meeting. You may actually learn something. You may score more points by listening than you could by talking. And you’re more likely to get the support of the women in the room.

If a woman articulates an idea that you like, reinforce it before you build on it. Say “I like Sally’s idea,” before you embellish it and attempt to make it your own.

I’m not going to tell you to stop interrupting people — especially women — because that’s probably an impossible habit to break. But you could at least attempt to give the women you have interrupted a chance to finish their thoughts.

If you are in a senior position, consider how you might change your corporate culture to encourage more listening and less mansplaining. And model that behavior yourself.

Stop watching cable news and imagining that that’s an appropriate model for discourse. It’s not.

Find a woman you admire and trust, and humbly ask her advice about how you interact with women. Then listen a lot and talk sparingly. Think about what you are hearing.

For the women reading this (and admitting the risk that I am mansplaining once again), I have some advice as well.

Interrupt. That may not be your nature, but it may be the only chance you have of being heard.

Engage on an intellectual level. Some men are pigs who you’ll never win over — I hope there are very few of those in your career. But many will respond intellectually to an intellectual argument. Logic and facts will help you, because logic and facts have no gender.

And if a man seems receptive to learning about himself, please take the opportunity to educate him (gently, if possible) about what an ass he is being. You may be able to make someone better, as the women I worked with have improved me. This is not your responsibility — its ours — but those among us who are reflective about ourselves will be grateful.

How to make things better — don’t behave like an ass

It’s not easy to write about what an ass I used to be. I’m sure that some of my readers — and perhaps some of my former colleagues — will be angry at what I have described. I hope that you can accept this confession in the spirit in which I offered it, as a penance and an invitation to create insight and dialogue.

Regarding the discussion that will follow, I want to be clear about this:

I will, as always, delete any personal attacks in the comments. If you are angry at what I have written, that’s fine, but there’s no place for name-calling directed at me or at other commenters. This blog is a place for civil discourse.

If, however, you want to describe your own experiences, contribute to the discussion, criticize my advice, or offer your own, I’d be grateful. Gender bias has made workplace interactions less effective. If you think you can help change that, I welcome your views.

Enjoyed your article. Here’s a salient comment from me.

You wrote:

<>

I am a woman. I truly dislike when people interrupt me. But I will not take your advice and interrupt them. I will instead call them on their incivility.

After the person who has interrupted me stops talking, here’s what I say to them:

“You interrupted me. I wanted to tell you….(finish my thought)”

When someone interrupts me in a truly rude way, such as supplying a word after I pause for half a nanosecond in conversation, I challenge them by saying. “You cannot read my mind. What I wanted to say was …”

The only way to stop interrupters is to call them on their behaviour. It’s important to deal with them as the bullies they are. Let’s advocate for better conversational manners. It’s a small step toward making human intercourse a little less fraught.

“I’m not going to tell you to stop interrupting people — especially women — because that’s probably an impossible habit to break. But you could at least attempt to give the women you have interrupted a chance to finish their thoughts.” — This problem is real. When you’re on the receiving end, it interrupts your thoughts. If you want to finish your sentence, you have to hang on to it despite what the interrupter is saying, while you wait for them to finish saying what they think you were about to say. That’s not always possible, and it’s immensely frustrating to lose the end of your sentences. Really.

But I believe people can change — unconscious incompetence – conscious incompetence – conscious competence – unconscious competence. That’s how it’s done. Just decide to break the habit. Keep your own score. Give yourself a reward as you progress.

It’s generally easier for men’s voices to drown out women’s, and men are often much more competitive about “stage time”. It’s easier for women to stay silent than it is for them to break in. But everyone is leaving important thoughts and collaborations on the table. One way to change this is to speak only a few sentences and then listen for a few sentences. At first, there may be silences. Allow them. Look directly at the person you’re speaking with. Make eye contact. You’ll be amazed at what happens when you give someone your undivided attention and genuine interest in what they have to say.

I appreciate your shining a light on personal examples of women whose intelligence you admire. To write about it without mansplaining, I suggest you interview women and write their thoughts about it. Your questions, their answers. Also, interview men about women whose intelligence they admire.

Thanks for bringing this subject to light. It’s not just right and left, red and blue civil discourse that needs our attention…

Women have been deeply hurt by the ignorant mansplaining that’s been done by our political representatives and translated into policies that affect us on a very personal level.

Gender bias and sweeping generalisations.

I wonder if some strategies from relationship counselling might be useful for persistent interrupters. Focusing on one workplace relationship where interruptions are an issue and using a ‘Talking stick’ or a ‘reflecting conversation’ structure would help you to become conscious of your interruptions and hone your listening skills.

“One way to change this is to speak only a few sentences and then listen for a few sentences. At first, there may be silences. Allow them. Look directly at the person you’re speaking with. Make eye contact. You’ll be amazed at what happens when you give someone your undivided attention and genuine interest in what they have to say.”

Agree wholeheartedly Joanne! Such great advice. I find this also helps build relationships which leads to both parties being less likely to interrupt (or at least being more apologetic about it). Unfortunately I interrupt far too often, most often because I’m excited to add to their thoughts and want to show I agree and/or understand what they’re saying. This isn’t helpful for them though! The conscious eye contact and allowing room for silences really helps with this.

Here’s another tip for men to avoid the appearance of Mansplaining: ask more questions than you offer statements. And rather than offering your brilliant insight/idea as a declaration, maybe preface it by asking “Do you think it would be a good idea if we…”

Haha – Josh, thanks for this! You explaining your mansplaining is just too good to be true. This is what I always liked about you – you’re a good person at heart.

i know people-including myself-who interrupt because we have(what we think is) an exciting thought and we are afraid that we will forget it if we don’t blurt it right out. it is helpful to keep silent and to write a quick note. also, interrupting is more acceptable(to me) when prefaced by a phrase such as, “oh, sorry to interrupt, but did you mean….?”

And it’s listening. Sometimes just listening so you don’t repeat or cut off the person. I call my friends out on it now – they have asked me to. They want to learn. So I do. One thing to is for people to ask themselves, “is the point I am going to make important to the convo or is it just to show off / demo that I KNOW more..?” If, for example, it was a technicality or a matter of law that had high-stakes, yes, it’s important to bring up. When a man cuts me off and says, “Actually…” that is a big clue that mansplaining is coming….and way too often it’s followed by a) information that is not relevant to the convo and it’s trying to hold higher status; b) it assumes as you say that I don’t know. And often times, I DO know. I often know more than the man trying to explain it to me. What mansplainers should know – you lose credibility with women and other men. If women are decision-makers, good luck. It matters. Thank you for being honest. Yes, you’ve mansplained to me. We’re friends. And I adore you because you admit it, own it and get it. Thank you!

All this whining about how some men explainth to women too much misses the bigger point. Mansplaining is not about women. It’s about good communication skills, or the lackthereof. Gender isn’t the problem. A lack of etiquette (and the absence of an a-ha moment and a little empathy) is the culprit.

Wise man, insightful

So you’re basically a man mansplaining what is mansplaining. Good. “Not sure” you understood anything here.

Another great article!

Couple of thoughts: I would have liked some more details or examples of how you discovered you were mansplaining. I got to the section on advice and was surprised because I thought you were still building up. It seems like you have diagnosed yourself statistically: most accomplished men with explainy-type jobs will be (unconscious?) mansplainers, therefore so are you.

Re: “you probably can’t stop interrupting”, thank you. I am a chronic interrupter. It is an autistic thing. We lack the sensory wiring that tells us when it’s our turn to speak so we end up with awkward pauses and interruptions. That said, there are interruptions for various reasons. I think it’s important to always strive for authenticity and to not make excuses for one’s self.

And then, regarding your advice to women. I appreciate it very much. However, when deal with a bad faith communicator, a focus on facts and objectivity can make things worse. If mansplainers do what they do because they believe men are inherently superior in mind to women, then a fact based argument proving the contrary is likely to inflame already swollen and delicate egos. I find that the strategy for dealing with ‘splainers will be contextual and dependent on the desired outcome. Often it’s just more effective to go around them than through them.

How I learned — a combination of reading about and awareness raising based on media, and some well placed hints from women I trusted.

Most mansplainers are not bad faith communicators. They are earnestly trying to be share their knowledge and are insufficiently sensitive to what others are thinking. It is possible to help them see the error of their ways.

As far as actual bad faith communicators — any strategy that works with them is fine with me!