An editor’s notebook: When it comes to metaphors, don’t be a slut

Editors deal in meaning. Metaphors are great for meaning — until they get out of hand. What do you tell an author whose relationship with metaphors has become promiscuous?

Editors deal in meaning. Metaphors are great for meaning — until they get out of hand. What do you tell an author whose relationship with metaphors has become promiscuous?

Today’s example, like yesterday’s, comes from a book I was editing. The author had great ideas and an engaging writing style, but occasionally got carried away. Here are a few passages from different chapters in that book (and I’m grateful to the author for allowing me to post these in their pre-edited form):

Then David showed up. Unlike his older brothers, he was still too young for the army. He owned no sword, no shield. Nonetheless, he took one look at Goliath, listened to his loud bluster, and decided to take him on. Do you remember that famous picture of a lone Chinese protester standing in front of a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square? That’s what this clash was looking like.

What is niche domination? It’s creating, or moving into, a market space narrow enough that you can become the big fish, and expansive (or expand-able) enough that you can make great revenue as you grow it.

Maybe you’re not content to be a cog in someone else’s wheel – a grey-suited drone buried in the cubicles of corporate life. Some people are content to be little fish in a huge pond, but you have higher aspirations. By focusing on a tightly-defined niche, you and your business can become a major player. Perhaps THE major player.

That’s not to say that companies can’t stretch their capabilities and offerings into new or adjacent areas. That can be a very successful strategy. But if there isn’t a 20/20 focus on what the core competencies are, along with identification of the best-hanging fruit of opportunity (sometime the lowest-hanging fruit is rotten at the core), businesses easily lose their way and impede real progress.

In the corporate world, what do various vertical domains, such as Healthcare, Education, Aerospace, Retail, etc. have in common? This: there are functional areas that are common to many businesses. HR. Training. Compliance. Software apps. Fleet services. IT. Think of these functional areas as horizontal lines, that cut across many verticals. . . . Are your right-sized clients nimble start-ups or slow-moving mature companies? Micro, Small, Medium, or Large business? Divisions of big companies? Think of a diagonal line, with small at the lower-left, and huge at upper right. Where’s your sweet spot?

I loved this author’s enthusiasm, but he needed a little reining in. What would you tell an author like this?

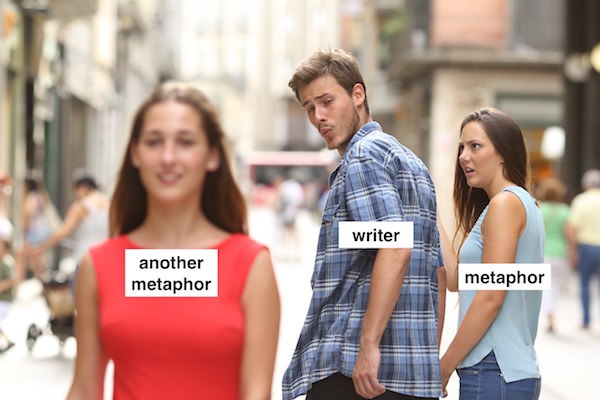

Metaphors are like lovers — you should remain loyal to one at a time

I have no problem with authors adopting metaphors for a while and then switching. Think of it as serial monogamy — you don’t flirt with a new metaphor until you’ve ended things with the old one.

Authors with any sense will immediately recognize the issue once you point it out. This is why I typically add editorial comments on these, leaving it to the author to fix, rather than suggesting specific word edits. Here are the comments I added on the passages above:

- On the David/Goliath/Tiananmen Square passage: My comment was “Your metaphor doesn’t need another metaphor to explain it.” Since the author was in the midst of an extended and vivid metaphor about David and Goliath, no further clarification was needed. I suggested deleting everything about the Chinese protestor, since you don’t want to flirt with Tiananmen Square when you’re already in a committed relationship with the Israelites and the Philistines.

- On niche domination: Narrow/expansive market spaces generate a physical image at odds with “big fish.” My comment: “Metaphors again. Big fish in market spaces?” And I recommended replacing big fish with the less vivid, but less confusing, “dominant player.”

- On cogs/drones/fish/niches: “Fish, cogs – metaphor confusion again. And it’s very different to be a cog (bit player in a large company) vs. a little fish in a huge pond (commodity supplier with lots of competitors). This paragraph needs rethinking. What are you railing against – corporate cog-hood or ordinary consultant-hood? Probably the latter, so dump the cog.”

- On best-hanging fruit: This was a case where the author probably had an interesting idea, but that idea got mangled during the process of typing it out. Since I couldn’t figure out what he meant, I wrote: “This confused me too. I don’t know what ‘best-hanging fruit’ means – is your target customer well-hung? And ‘Sometimes the lowest-hanging fruit is rotten to the core’ – am I supposed to avoid low-hanging fruit? Please rewrite to clarify what you mean.” Sometimes, when the author has confused you, the best course it to describe the confusion — you can’t suggest a fix if you can’t figure out the intended meaning.

- On verticals, horizontals, and diagonals: The metaphor of vertical industries is common; people understand it as the difference between healthcare and retail, for example. And with that established, you could probably get away with thinking of departments as horizontals. But if you do that, you can’t talk about diagonals later in the chapter without scrambling people’s brains. My comment: “Why a diagonal line? How does this line match up with your vertical lines, horizontal lines, and geographical boundaries? Metaphorical confusion!”

My advice for authors and editors about metaphors

Sure, it’s lots of fun to ridicule authors for metaphorical overload (The New Yorker has a running gag with fillers labelled “Block that Metaphor!”). But I sympathize with the poor authors. They’re just trying to be vivid, to do justice to the images in their heads.

My advice for authors is this: don’t sleep around with metaphors.

Sometimes they’re quick flings: just a suggestive word or phrase, quickly cited. That’s fine, but if you do it, let the reader breathe for a minute before making it with a different metaphor.

Sometimes they’re extended riffs. An extended metaphor (like my author’s David and Goliath) can be excellent, but once you’re inside one, stay faithful to it. You’ll signal the reader that you’re done with it by describing what you can learn from the metaphor — the “moral of the story.” After you’ve done that, you can move on to a different metaphor, but preferably not for the same concept.

And be especially cautious with visuals. The best thing about metaphors is the images they suggest. That’s also where the problems lie. Fish in narrow spaces, diagonal lines crossing verticals and horizontals, best-hanging fruit — these are the images that make readers go “huh?” A single misplaced word can be enough to throw someone off. Embrace your metaphors tenderly, and make sure your imagery does justice to their explanatory power.

As an editor, you want to be sensitive to these conflicting images. If your author is a smart writer, as mine was, they’ll react immediately once you point out the image confusion. As you can see from my comments, I don’t mind being a little snarky as I point out these problems: I think it motivates authors to recognize the silliness of what they’ve inadvertently created. Once they have the realization, they can’t unsee it — and they’ll do the work of keeping the metaphor in the text faithful and monogamous.

You did exactly what I good editor should in this case: Remind the author of the curse of knowledge.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curse_of_knowledge

I think about this quite a bit since I heard the term maybe seven years ago.

Phil,

When a writer suffers from the Curse of Knowledge, s/he talks over their readers’ heads, using unfamiliar terms and obscure references. This writers was striving to do exactly the opposite.

I used to love The New Yorker’s “Block That Metaphor” fillers at the end of columns (all edited by E. B. White, BTW). I even contributed one, from the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle in the late 70s — “‘We missed the boat a couple of years ago,’ the police official said. ‘They caught us with our pants down, and we’ve been playing catch-up ball ever since.’”

Awesome!