Writing, printing, and permanence

Words make pages, which make books. Behind that simple statement is the rich history of the mechanisms of printing. My personal history is a thread in the the broader history of the methods by which words reach the eyes of the reader — a narrative that came to life for me when I recently visited the Museum of Printing in Haverhill, Massachusetts.

My wife and I recently made a pact. One of us would select a small, obscure museum to visit, and the other was compelled to agree. Our first selection was the Museum of Printing.

The museum is an unassuming brick building in a working-class suburb of Boston — if you didn’t know better, you might assume that the building was the home of some small local electronics or manufacturing business.

Inside, though, are a wide variety of displays and machines, large and small, in roughly chronological order. The first thing you encounter is this incredible press. The eagle on the top is not a decoration, it is a counterweight.

The message of this imposing device is, simply, “printing matters.” And it does. As I’ve seen in my own personal career, the technology that people use to turn words into printed (and later, electronically distributed) material has a profound impact on what you can write, who controls it, and who reads it.

The successors to presses like this, throughout the 1800s, were platen-based presses that made it a lot easier to produce multiple copies of single pages. Whatever you were printing still had to be laid out with individual cast bits of type, just as in the days of Gutenberg and the European printers who followed him, but now you could run off sheets and distribute them to the masses as flyers protesting slavery or whatever.

But everything changed in 1884 when Ottman Merganthaler invented the Linotype machine. Now an operator could sit at a keyboard and type characters, and the machine would automatically select letterforms from a collection of bins, line them up in order (even adding spacing to allow type that was fully justified on both sides), and then cast the resulting collection of characters into a full line of type in a single lead slug. You could then take the resulting lines of type and lay them out in a page and print it, with the page layout vastly accelerated over the process of placing characters individually.

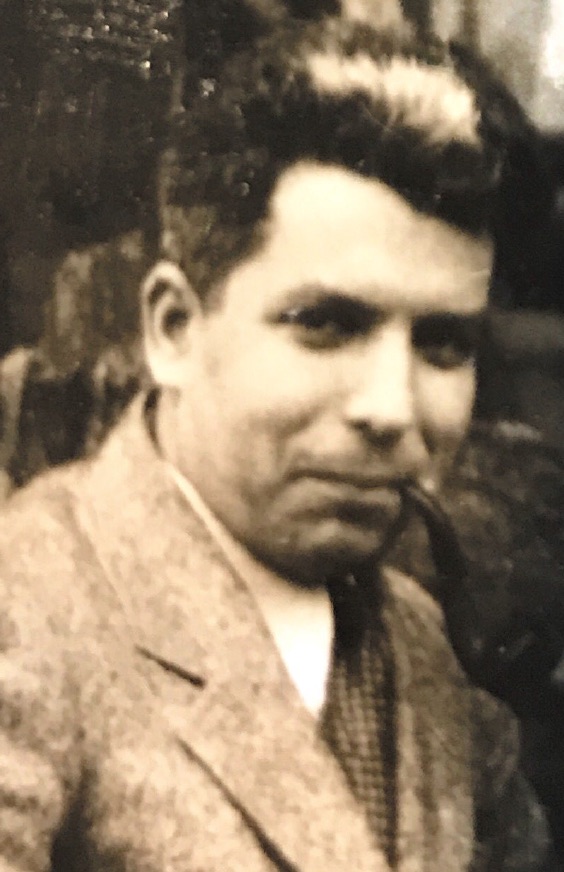

This is where the narrative intersects my own personal history. My grandfather, Saul Bernoff, was a Linotype operator for several printing organizations in Philadelphia. He was a Russian immigrant, born in 1901, a union man working the night shift and operating a huge machine to turn typewritten sheets into type for printing. Like nearly all Linotype operators, the tips of fingers had been burned insensible so many times that he could pick up a hot baked potato with his bare hands.

While operating a Linotype was a blue collar job, it demanded a writer’s soul. The operator had to know where to hyphenate words and when to request help because somebody had asked an erroneous sentence to be set into type. My grandfather was a self-educated man and his apartment was full of books in a hand-made bookshelf built into the wall. And, bless his soul, Saul Bernoff had a small desktop platen press in his basement and would occasionally print his own flyers, because he knew from his everyday work the power of turning words into something you could hold in your hand.

Printers’ ink is in my blood.

Before the Linotype, newspapers were generally limited to eight pages. Laying out more than that, one character at a time, was just too time consuming. But with an operator and a keyboard churning out a whole line at a time, you could far more easily print longer works. You can trace the explosion in newspapers, presses, and books in the early Twentieth Century directly to the advent of the Linotype machine and the printing presses, increasingly automated, that it fed.

The next advance in page layout also overlaps with personal history. As you can see from more of these hulking machines lovingly preserved at the Museum of Printing, the successor to the linotype was phototypesetting, in which the output was not lead type but blocks of type generated by exposing letterforms photographically.

Soon after arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts to go to graduate school in 1979, I found myself as a volunteer working for the New England Science Fiction Association. They sent me to a phototypesetting place near Harvard where I turned typewritten material into sheets of glossy photographically typeset type for the program book of the World Science Fiction Convention for 1980, Noreascon.

It was here that I learned about pasteup. You would take these sheets of type and run them through a waxing machine, putting sticky wax on the back, then stick them down on a layout sheet on a light table. Once you’d laid these sheets out, you’d send them to the printer, who would take a photograph and turn that into a printing plate to print thousands of copies.

I was hooked. I loved to write. But now I knew how writing turned into printing. This changed the course of my career. I eventually quit graduate school and took a job as a technical writer. I learned about coding material for printing with a typesetting language called Runoff, and then watched as what I wrote got printed in technical manuals distributed with software.

And when I took my next job, I found myself in charge of that whole process, managing a team of technical writers and editors as well as a graphic designer who would turn what we wrote into phototypeset material, paste it up, and make beautiful two-color bound books from it.

I found myself working next for a small startup. And I had decided that pasteup was clumsy and slow. This was the mid-eighties, and Aldus Pagemaker, laser printers, Macintoshes had introduced the world to desktop publishing. But I wanted an efficient process that turned a stream of type into beautifully printed material — desktop publishing was too much of a one-page-at-a-time effort to be efficient for a real writer. I learned way too much about the HP Laserjet printer, worked with the founder and chief engineer of my company to generate screen snapshots in laser-printer-ready format, and hacked it all together to create my own efficient desktop publishing system.

Right there on the copyright page of my manual it said, in moderately small type, “No pasteup.” Somehow, I think all this hacking of computers and printers would have made my grandfather proud.

After that I ended up in charge of print production — basically page layout — for an actual startup publishing company. We used a tool called Ventura Publisher which actually accomplished my dream, efficiently turning streams of type from authors into printed pages.

Is it any wonder that I ended up a prolific blogger — with my fingertips on the means of production to thousands of readers with no need for printing at all?

It’s been 130 years since the advent of the Linotype. I’ve been writing and laying out pages and making books and blog posts and all manner of creations made of type for 40 of those years. And what I’ve learned is that you cannot separate writing from the technology of production. People wrote differently for handwritten material that would be turned into laboriously laid out bits of type than they did for typewritten material destined for a Linotype, than they did for phototypeset material composed on a keyboard and laid out with hot wax, than they did desktop publishing and laser printing, than they do now for blogs and ebooks.

If you love books, it pays to know how people create them. It’s not just type flowing effortlessly onto a page. You could hold a Linotype slug in your hand, or a shiny waxed phototypeset page, or a printed book. Words to me are physical objects that demand the same attention as any other carefully manufactured and created thing. They have heft. They have impact.

I can type these words anywhere in the world and you can read them moments later. But I still have reverence for the power they have. And I think a lot of that dates back to presses with eagles on top and Linotype machines pumping out hot lead slugs that could burn your fingers.

Love this! Thanks for bringing it to everyone’s attention.

Fantastic read. Really loved this historical narrative!

Josh, your grandfather would have been very proud of you for carrying on the family printing tradition, and your father still is.