Words of wisdom for the Asimov centenary

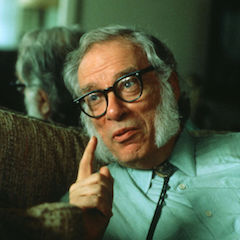

Isaac Asimov turned 100 years old yesterday. It’s a shame he didn’t live to see it, because we could use a man like him right now.

My admiration for Asimov started when I was very young. I read everything of his that I could get my hands on, since his highly accessible writing made it fascinating to read about the topics that I loved most: science and math.

Asimov had two qualities that I admire. The first was an ironclad commitment to the truth, especially in science. His was a clear voice for rationality and reasoning. Read Asimov and you not only learn about the world; you learn how to think.

The second quality, which has also become a beacon for me, is that Asimov was a perpetual, peripatetic, and unstoppable writer. His idea of life was to research just about anything — mathematics, astronomy, the Roman Empire, the Bible, Shakespeare — and then write about it in the most engaging way possible. I said “his idea of life,” not “his idea of work,” because Asimov wrote from morning to night, every day, even bringing his typewriter on vacation. Writing was fun for him; he lived in flow. Everything else was secondary.

Asimov’s wisdom

In a world of fake news, sentimentality, and political demagoguery, we need a commitment to truth and rationality more than ever. If Asimov were alive today, I have no doubt that he would be a standard-bearer for science and clarity and an opponent to the mush-brained emotional shouting that now passes for political dialogue.

Since he’s not here to lead us, we’re left to lean on what he wrote. Luckily, there’s plenty of that wisdom to cherish. If you need sources, they are here.

On truth

It is change, continuing change, inevitable change, that is the dominant factor in society today. No sensible decision can be made any longer without taking into account not only the world as it is, but the world as it will be … This, in turn, means that our statesmen, our businessmen, our everyman must take on a science fictional way of thinking.

There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that “my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.”

[N]o matter how outrageous a lie may be, it will be accepted if stated loudly enough and often enough.

There has never been any custom, however useless it may become with changing conditions, that isn’t clung to desperately simply because it is something old and familiar.

On science and religion

The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not ‘Eureka!’, but ‘That’s funny …’

The saddest aspect of life right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.

Science doesn’t purvey absolute truth. Science is a mechanism. It’s a way of trying to improve your knowledge of nature. It’s a system for testing your thoughts against the universe and seeing whether they match. And this works, not just for the ordinary aspects of science, but for all of life. I should think people would want to know that what they know is truly what the universe is like, or at least as close as they can get to it.

Inspect every piece of pseudoscience and you will find a security blanket, a thumb to suck, a skirt to hold. What does the scientist have to offer in exchange? Uncertainty! Insecurity!

How often people speak of art and science as though they were two entirely different things, with no interconnection. An artist is emotional, they think, and uses only his intuition; he sees all at once and has no need of reason. A scientist is cold, they think, and uses only his reason; he argues carefully step by step, and needs no imagination. That is all wrong. The true artist is quite rational as well as imaginative and knows what he is doing; if he does not, his art suffers. The true scientist is quite imaginative as well as rational, and sometimes leaps to solutions where reason can follow only slowly; if he does not, his science suffers.

There are many aspects of the universe that still cannot be explained satisfactorily by science; but ignorance only implies ignorance that may someday be conquered. To surrender to ignorance and call it God has always been premature, and it remains premature today.

I am an atheist, out and out. It took me a long time to say it. I’ve been an atheist for years and years, but somehow I felt it was intellectually unrespectable to say one was an atheist, because it assumed knowledge that one didn’t have. Somehow, it was better to say one was a humanist or an agnostic. I finally decided that I’m a creature of emotion as well as of reason. Emotionally, I am an atheist. I don’t have the evidence to prove that God doesn’t exist, but I so strongly suspect he doesn’t that I don’t want to waste my time.

I believe that only scientists can understand the universe. It is not so much that I have confidence in scientists being right, but that I have so much in nonscientists being wrong.

On war and destiny

Violence is the last refuge of the incompetent.

It is an odd fact that anyone who wishes to start a war must always make it appear that he is fighting in a just cause even if the real motive is naked aggression. Fortunately for the would-be aggressor, a “just cause” is very easy to find.

The military mind remains unparalleled as a vehicle of creative stupidity.

[In 1980] To tell the truth, I don’t think the odds are very good that we can solve our immediate problems. I think the chances that civilization will survive more than another 30 years—that it will still be flourishing in 2010—are less than 50 percent.

On writing, and his legacy

Ideas are cheap. It’s only what you do with them that counts.

Writing is hard work. The fact that I love doing it doesn’t make it less hard work. People who love tennis will sweat themselves to exhaustion playing it, and the love of the game doesn’t stop the sweating. The casual assumption that writers are unemployed bums because they don’t go to the office and don’t have a boss is something every writer has to live with. I have never known a writer who hasn’t suffered as a result of this, hasn’t resented it, and hasn’t dreamed of murdering the next person who says “Boy, you’ve sure got it made. You just sit there and toss off a story or something whenever you feel like it.”

I made up my mind long ago to follow one cardinal rule in all my writing — to be clear. I have given up all thought of writing poetically or symbolically or experimentally, or in any of the other modes that might (if I were good enough) get me a Pulitzer prize. I would write merely clearly and in this way establish a warm relationship between myself and my readers, and the professional critics — Well, they can do whatever they wish.

[Writing] is an addiction more powerful than alcohol, than nicotine, than crack. I could not conceive of not writing.

I was once being interviewed by Barbara Walters…In between two of the segments she asked me…”But what would you do if the doctor gave you only six months to live?” I said, “Type faster.”

What I will be remembered for are the Foundation Trilogy and the Three Laws of Robotics. What I want to be remembered for is no one book, or no dozen books. Any single thing I have written can be paralleled or even surpassed by something someone else has done. However, my total corpus for quantity, quality and variety can be duplicated by no one else. That is what I want to be remembered for.

Be inspired

I miss you, Isaac.

I am doing my best to light up the darkness. I am typing as fast as I can.

Let’s hope that some few others may do the same, so that our civilization can survive its darkest impulses.

Well Done 🙂

Why did he write like he’s running out of time?

Ah, that was Hamilton, but Asimov was similarly afflicted.

Thank you for pulling out some of his most thought-provoking quotes. I love how he was both nuanced and yet blunt.

He was one hell of a mind, and his impact has been profound.

TWO THUMBS UP

I feel I have a connection . . . I attended two of his keynotes, 25 years apart . . . and amazingly enough, he called on ME during Q&A at the end, BOTH TIMES, and I asked the same question BOTH TIMES, and he delivered the same entertaining and educational answer BOTH TIMES … to the delight of thousands of ‘us’ in BOTH audiences!

Here’s to you, Isaac!

And thank you Josh for helping me remember!

Excellent, thought-provoking article. Sharing on social media.

His thought is intriguing, but it what is lacking for me is his thought in context of his relationships.