When to break my writing rules

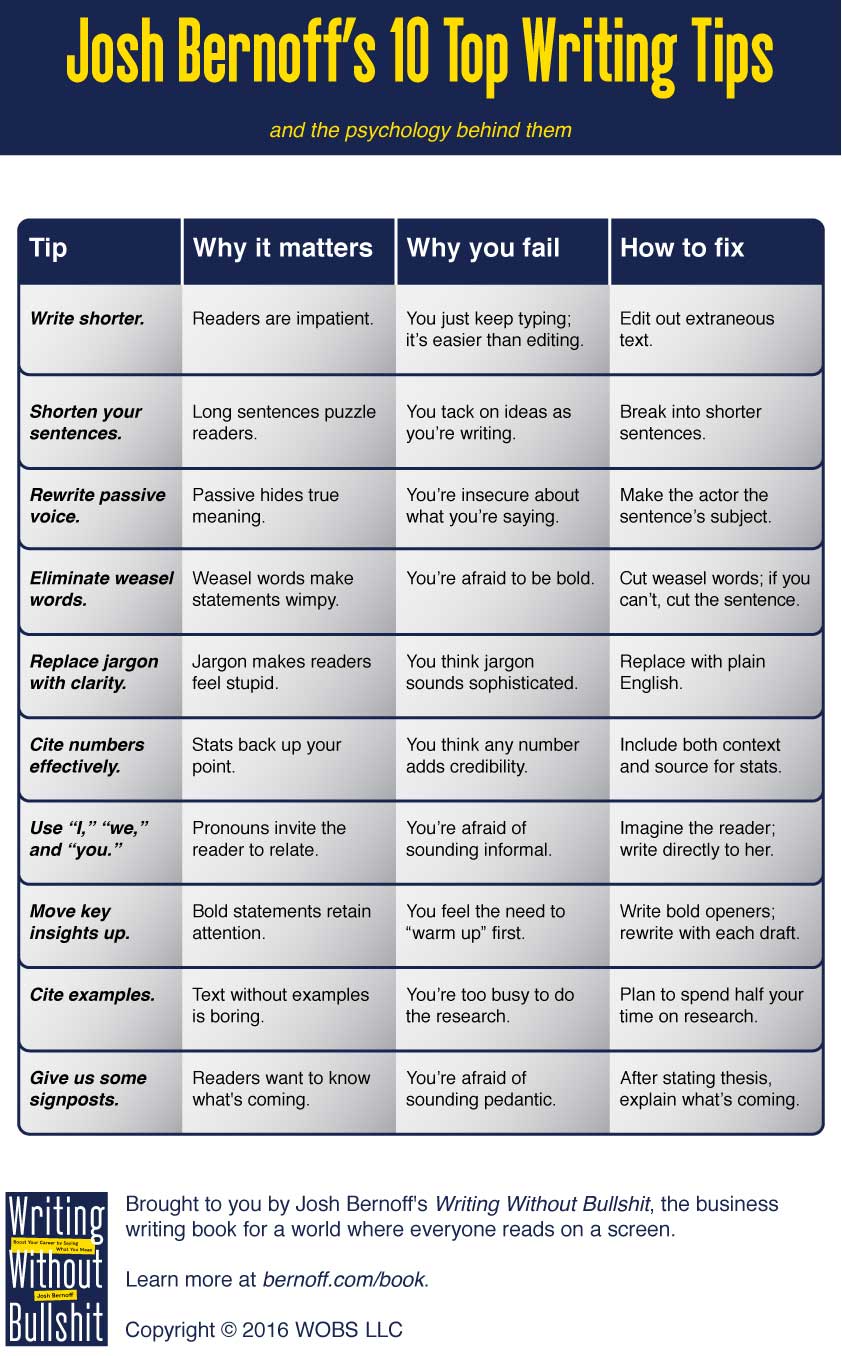

My most popular post ever included ten writing tips and the psychology behind them. On social media, I see people reading these tips with no context and objecting. “Passive voice is perfectly fine,” they say, or, “You wouldn’t get very far if you only used short sentences.”

You want to break my rules? I’m here to tell you the right way to break them.

Let’s start with this: these are not ironclad rules like the rules of physics. They’re not even rules you should follow whenever possible, like the Ten Commandments. They’re guidelines.

They exist because of excess. It is the excessive pileup of passive sentences, jargon, weasel words, and other useless detritus that makes your writing impenetrable. I’m not here to tell you give up jargon for lent — just to cut it way back.

Think of me as your coach. I’m not going to tell you that you can never eat a cookie. But if you eat cookies all the time, you’re not going to get much healthier. The questions are, how often do you eat cookies, do you habitually eat cookies, and wouldn’t you be happier if you had a lot fewer cookies in your diet?

So here are the ten rules and how to break them:

1 Write shorter.

How to use this guideline: Every format has an ideal maximum length — two or three hundred words for an email, 1,500 for a blog post, and so on. Start with those limits in mind, and cut extraneous sections, sentences, and words that are bulking up your writing. Make every word work.

When to break the rule: Writing intended to entertain, whether fiction or nonfiction, can be long and engaging. And some concepts, even in business settings, need more detailed explanations.

How to break the rule: If you’re writing something detailed, include an executive summary. Put less interesting technical details in an appendix. And use bullets and graphics to make the text easier to scan.

2 Shorten your sentences.

How to use this guideline: Sentences are not minivans — you can’t just keep cramming ideas into them. If your sentences have grown to be too long to parse, break them down.

When to break the rule: You can create rhythm with the contrast of long and short sentences. If you find your writing has become staccato, you’ve probably gone too far with the short sentences.

How to break the rule. Long sentences are easier to parse with structural elements that ease navigation. Use dashes and semicolons to separate clauses. Long sentences can work if they include elements in an easily parsed series

3 Rewrite passive voice.

How to use this guideline: Passive voice is a habit. Break it. If you continually write sentences where the subject of the sentence is not the actor, you’re creating confusion and uneasiness in the reader. The objective is not to eliminate every passive-voice sentence, but to cut way back on the repetition.

When to break the rule: Sometimes the actor is unimportant or unknown — it’s ok to say “My purse was stolen.” And sometimes you want to emphasize the object of the action, for example: “The problem with insults is how they are used in place of legitimate arguments.” Certain forms of content, such as scientific papers, insist on passive voice to avoid making it seems as if they’re drawing attention to the authors.

How to break the rule: For every passive-voice sentence, you need a reason. Don’t just use it out of habit. Use it when you’re making a point, or when the corresponding active-voice sentence is misleading.

4 Eliminate weasel words.

How to use this guideline: As with passive voice, the problem here is repetition. If your density of weasel words exceeds 3%, you’re going to sound like a bullshitter. Get rid of as many hedges and vague intensifiers as you can.

When to break the rule: You wouldn’t get very far without using the word “very.” But as with passives, you want to eliminate as many instances of words like “incredible” and “state-of-the-art” as you can. Review each weasel word and ask, “Can I get rid of this? Can I replace it with an actual number?”

How to break the rule: Reserve intensifiers and qualifiers for the most important sentences in your document. Then they’ll stand out.

5 Replace jargon with clarity.

How to use this guideline: Jargon is the third element of toxic prose, along with passive voice and weasel words. As with all toxic prose, the challenge is to reduce it, not eliminate it completely.

When to break the rule: Choose jargon words that your reader will know — and that are hard to write around. You might have to use “omnichannel” with e-commerce developers or “ontology” with AI practitioners. For each jargon word you use, ask, “Is including this word making it easier for my reader to figure out what I mean, or harder?”

How to break the rule: If you want to include a jargon word, use one that nearly everyone in your audience will understand. If not, add a definition up-front.

6 Cite numbers effectively.

How to use this guideline: If you include statistics, ensure that the sources are credible and that you haven’t exaggerated the precision. Include a link to the source.

When to break the rule: Imprecise and poorly sourced numbers don’t belong in your prose at all — if you must use them, add appropriate warnings.

How to break the rule: Include words like “about” or “approximately,” or warn readers that the source is questionable.

7 Use “I,” “we,” and “you.”

How to use this guideline: When you have an opinion, take credit for it. And use “you” to tell readers what you think they should do. (Don’t overdo it with the first person — repeating “I” and “we” sounds conceited.)

When to break the rule: Don’t take credit for others’ work. And don’t write “you” if your audience is too diverse to identify with what you write (but that’s a separate problem).

How to break the rule: To avoid repeating “you,” use commands. To avoid repeating “I” or “we,” make statements that readers can easily identify as your opinion.

8 Move key insights up.

How to use this guideline: Put the best information earlier in what you write. Get to the, point, succinctly, in the first few sentences.

When to break the rule: Sometimes you need to explain the antecedents of what you believe. But keep introductory ramblings to a minimum.

How to break the rule: State the point first, then back up and explain how you got there. If it really helps retain interest, begin with a story, but keep it short.

9 Cite examples.

How to use this guideline: Cite instances that prove your point, especially from interviews and public sources.

When to break the rule: When there’s no evidence to prove you’re right.

How to break the rule: Use analogies, appeal to common sense, or show how your perspective follows from what you’ve already proven.

10 Give us some signposts.

How to use this guideline: Describe what’s coming in subsequent sections in the document.

When to break the rule: If the document is short enough (or entertaining enough), you don’t need signposts.

How to break the rule: Write short and be fascinating.

Public TV and radio provide a good example of appropriate use of the passive voice: “Support was provided by .” They could say “The Ford Foundation, The Macarthur Foundation, The Richie Rich Family, Boeing, …, provided support,” but it would be confusing since listeners wouldn’t know what the list referred to until the end of the sentence.

PS, I once created a fake certificate for an editor friend as a joke. It said “Association of Professional Editers: Active Voice Spoken Here”

I love the single deliberate misspelling in that fake certificate! Brilliant!!

Thanks. That’s one of three jokes in the certificate.