What we say, and what we actually mean, about the Paris attacks

I am strongly, deeply, and clearly opposed to the terrorist attacks in Paris.

I am strongly, deeply, and clearly opposed to the terrorist attacks in Paris.

Sounds strangely flat, doesn’t it? Why state what everyone knows? Shouldn’t I be writing about thoughts and prayers, or the causes of terrorism, or vengeance, or something?

As I watched the flood of messages on social media this weekend, I became fascinated by what we say, what we really mean, and what we don’t say in a moment of crisis. People post emotionally, but what they post doesn’t match their actual emotions. Step back and seek a higher, more thoughtful truth. I have no idea if that’s even possible here, but I want to try.

What we don’t say

Here are some things many of us feel, but cannot post.

“I am afraid.”

“I am angry.”

“I am ashamed to be part of a human race that is capable of this atrocity.”

“I don’t actually know what is the right thing to do next.”

“Help me to know how to feel about Muslims in the wake of this tragedy.”

“War seems inevitable, but war is what got us here in the first place.”

If we feel these things, we cannot admit them. At the same time, we feel we must post something. So we post things that mean something different from what we actually feel. For example . . .

Thoughts and prayers

What we post: “My thoughts and prayers are with the victims of the Paris attacks.”

Why we actually mean: “I feel I must say something in the wake of this horrific moment, but I have only emotion. There is nothing I can do but think and pray. So I will write that I am thinking and praying. This makes me feel a little better.”

Does it help? It helps the person who posts it. I don’t think this does much for the Parisians. (Those who believe in the power of prayer will feel differently, and I respect that.) In the days after the Boston Marathon attacks, the city was wounded and hurting, but we drew our support mostly from our families and our neighbors, not from the rest of the country or the rest of the world. If you post this, I understand that you are sincere. Perhaps that is enough.

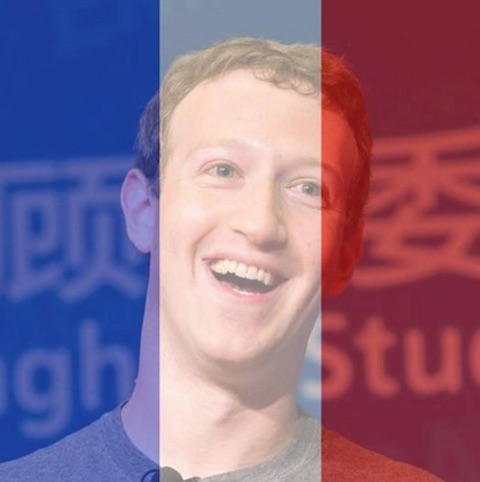

Profile pictures

What we post: We change our profile pictures to the colors of the French flag.

What we actually mean: This is an expression of solidarity and sympathy.

Does it help? I’m sure if you’re French, seeing all those French flags on Facebook is a small comfort. But this is not like the U.S. Supreme Court’s gay marriage decision, which caused so many to post their profile in rainbow colors. Not everyone agreed with the Supreme Court, but every one of my Facebook friends, and yours, is in sympathy with the French, and opposed to the terrorists. If everyone backs something, why bother to shout about it?

I resist “required” communications, since statements under duress mean nothing. If I don’t change my profile picture — and I haven’t — does this make me a terrorist sympathizer? Anti-French? I sure hope not, because I love France and have many cherished memories of the place and the people there. But I really don’t want to have to take a tricolored loyalty oath.

Don’t forget the other deaths

What we post: “Did you notice that terrorists also killed people in Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq, and Kenya?”

What we actually mean: “I feel guilty about only thinking of French victims when there are others.”

Does it help? It helps us to understand this is a global conflict. But there is no way to compare victims or tragedies. If it’s your mother or brother or husband, it’s the worst tragedy for you, regardless of whether the victim is Russian, Iraqi, or French. Trust me, nobody thinks this is just a French issue.

Here’s a link that explains this

What we post: Links to news stories that purport to explain the Islamic State and its attacks.

What we actually mean: “I want to understand.”

Does it help? While knowledge is always better than ignorance, efforts by our western minds to understand and explain Daesh (the Islamic State) are unlikely to get very far. I have real trouble understanding the minds of people who believe in religious beheadings, forced marriage, and slavery.

Here’s what we should do next

What we post: A suggestion or a link to an article that suggests a course of action. It’s typically either bombing the crap out of Daesh, or doing nothing because our wars in the Middle East have helped create this chaos, or more spying for stronger intelligence, or a call to resist more spying on our own citizens. There is no consensus.

What we actually mean: “I’m angry and I want to do something.”

Does it help? I think making decisions right after an attack is rash. This is not a moment when you’ll be likely to win anybody over, either. I’m not advocating doing nothing. I’d like to see a plan with a little more thought behind it.

A final thought

Daesh has now made itself a mortal enemy of the United States, Russia, France, Germany, the UK, Iran, Iraq, and Bashar El-Assad’s government in Syria. Even Al Qaeda renounces them. This is a unique set of aligned interests. I don’t know what will happen next, but it’s not likely to go well for Daesh.

But I remember the Middle Eastern wars we supposedly “won,” like the first Iraq war, and “Mission Accomplished.” The impact of our actions in the next few months will rebound upon us a decade from now. I hope our leaders are thinking that through, because the people posting on Facebook certainly aren’t.

Good. Very good. Thinking honestly and carefully rather than reacting emotionally is hard but necessary.

I am French and I follow regularly your blog. I fully agree with you on the risk to over-react under the pressure of emotion. But this does not mean that you should not show emotion. Sharing emotion, even in a clumsy way, shows that you care and that we belong to the same humanity. It helps when we go through tough times…

It was for example a warm feeling to see your President Obama reacting very fast on TV after the attack in Paris. He actually expressed his support to the French people BEFORE our own President Hollande made his own speech on TV…

Emotion is inevitable and we welcome it when it’s genuine.

As I discussed this topic with my students, 7th grade, today I made sure to point out other religions can be radicalized–skin heads/white believing in a pure white race and claiming Christianity teaches this. There are many examples where religion is used as an excuse to do bad things. My students are genuinely seeking to understand the why of these and other attacks. I hope many classrooms will open discussions on the topic of terrorism & it’s role in our global community today.

Josh,

Great post!

Maybe it’s also helpful to look at who our “Facebook audience” is who sees our profile picture covered by the French flag: our Facebook friends. We post for them, to show them how this atrocity affects us emotionally. We may use euphemisms, because this audience is rather diverse, including odd colleagues we became “friends” with way back when. We may not want to spill our unfiltered emotions to all of them, so we put them in universally kind, politically correct wrapper.