What authors can learn from a new study on “you” vs. “we” pronouns

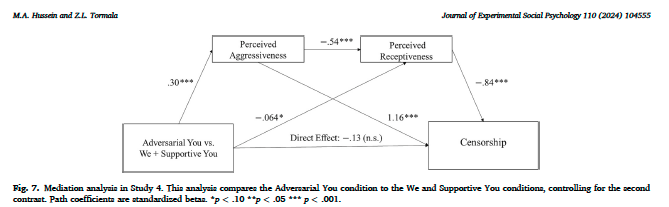

In the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Stanford University researchers Mohamed A. Hussein and Zakary L. Tormala published a paper titled “You versus we: How pronoun use shapes perceptions of receptiveness.” Thinkers and authors including Daniel Pink and Tamsen Webster have cited the study as justification for using “we” in persuasive contexts.

Is this research relevant for business books? Should you be using “we” more in what you write? Or, as the study’s authors might have suggested I put it, should we be using “we” more in what we write?

What the study really says

I have reviewed the full paper (not just the free abstract). But let’s start with the abstract, which appears to be an endorsement of “we” pronouns:

In response to increasing societal divisions, an extensive literature has emerged examining the construct of receptiveness. This literature suggests that signaling receptiveness to others confers a variety of interpersonal benefits, such as increased persuasiveness. How do people signal their receptiveness to others? The current

research investigates whether one of the most fundamental aspects of language—pronoun use—could shape perceptions of receptiveness. We find that in adversarial contexts, messages containing second-person pronouns (“you” pronouns) are perceived as less receptive than messages containing first-person plural pronouns (“we” pronouns). We demonstrate that “you” pronouns signal aggressiveness, which reduces perceived receptiveness. Moreover, we document that perceived receptiveness influences important downstream consequences such as persuasion, interest in future interaction, sharing intentions, and censorship likelihood. These findings contribute to a fast-growing literature on perceived receptiveness, uncover novel consequences of signaling receptiveness, and contribute to our understanding of how pronouns shape social perception.

However, once you dig into the paper, you notice that it is limited to “adversarial contexts.” For example, one of the five studies described in the paper shows that in the context of a review of a worker’s performance, using “you” renders the subject less receptive, as in the statement, “Your timeline was too relaxed, and you kept making errors along the way that delayed the project.” The other contexts explored in the paper include political arguments and social media posts.

Because these are acknowledged adversarial contexts, the recipient of these messages is primed to treat the person delivering the message as a potential threat. It’s no surprise to me that in such a context, “you” is perceived as threatening, and people are more receptive to “we.” As the authors of the paper state:

[O]ur research suggests that people who plan to express disagreement with someone or take an opposing stance on an issue would be well-advised to replace “you” pronouns with “we” pronouns in their messages to enhance their persuasiveness and increase recipients’ openness to their views.

What this means for authors

People don’t generally buy books that they are primed to disagree with. A person who reads the book’s flap copy, reads a description on Amazon or bookshop.org, or reads a review of the book somewhere has a pretty good idea what they are getting. If you buy a book that purports to enhance your level of productivity, suggest a better way to do digital marketing, improve your business writing, or enable your company to succeed by disrupting an industry, it’s pretty likely that you are already receptive to the author’s message.

So let’s look at “you” and “we” in this non-adversarial context.

“You” is particularly useful when giving advice, which is a lot of what business books do. Consider five ways you might write about brevity, for example:

- When you write in long, repetitive paragraphs, you tax the reader’s attention and generate frustration.

- Don’t write in long, repetitive paragraphs because you will tax the reader’s attention and generate frustration.

- When we write in long, repetitive paragraphs, we tax the reader’s attention and generate frustration.

- When one writes in long, repetitive paragraphs, one taxes the reader’s attention and generates frustration.

- Writing in long, repetitive paragraphs taxes the reader’s attention and generates frustration.

Option 1 using “you” establishes the author as an authority and teacher and the reader as student. It draws particular attention to the fact that this is advice: it basically says “Pay attention, this is something you need to do.”

Option 2 is a command. The reader understands that this is advice meant for them. The “you” is understood.

Option 3 using “we” is, as the paper suggests, less likely to generate resistance. But it implies that everybody reading the passage is in the same boat. If you write a whole advice book this way, it will rapidly become tedious. In fact, I think the reader is likely to rebel at some point and say, “Hey, wait a minute, I don’t do that, why are you assuming I have this problem?”

Option 4 using “one” distances the author from the reader. It is far easier for the reader to say “Ah, this advice is not meant for me, it’s for some unspecified ‘one.’ ” Readers will perceive a whole book written that way as descriptive, rather than prescriptive, which lets them off the hook.

Option 5 turns the advice into a statement and is far easier to swallow. But at some point you’re going to have to tell people what you want them to do. A book full of statements like this is easy for readers to read and ignore. You can’t get away with that sort of passive statement about the world in every context that calls for advice.

Some authors are uncomfortable with using “you” and commands repeatedly throughout the text. It’s true that the constant repetition of “You must do this” and “You must do that” turns the book into a lecture. So it’s a good idea to leaven your use of “you” and commands with other forms of argument to create a context in which the reader believes you, and is ready to accept your advice.

“We” is particularly helpful when you want to sweep the reader up into a warm and conspiratorial mindset. “We often aren’t as forgiving of ourselves as we ought to be,” for example, or “We’re inclined to pay less intention in meetings than we should, it’s just human nature.”

But despite what this study reports, “we” is not as effective as it needs to be in the context of advice. If you want a reader to accept you as an authority and take your advice, you’re going to have make a solid argument with evidence about why to trust you, and then you need to use “you” or commands to be clear about what you think then reader should be doing.

As an author, you must become comfortable with using “you.” Learn all the other techniques you can use to become persuasive, use them to create context, and then hit the reader with clear advice. Because in the end, readers will respect and recommend books that give them the advice they were seeking when they bought the book.

And that’s how you generate change in the world.

Fascinating and insightful. I’ve shared your post on LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/paulstregevsky_what-authors-can-learn-from-a-new-study-on-activity-7245114225981820930-1gQf?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop

An interesting analysis of the many ways in which various pronouns can and should be used, depending on the context and the intended audience.

I’m inclined to go with (in this example) “Long, repetitive paragraphs tax the reader’s attention and generate frustration.” I trust that the reader is intelligent enough to figure out if the statement applies personally.

I find that using “one” instead of “we” or “you” is helpful for pointing to more of an abstract point and then go to “we” or “you” variations for more direct observations, suggestions, etc.

I find it interesting that the example you provide is a don’t, rather than a do statement. Don’t statements do not provide advice or action items.

Of course, the better course would be the do statement, no matter which pronoun (or none) is used. Much more persuasive.

So, interestingly, the answer provided in the study is not of much importance, at least in your example. (I find the example great for your point about the potential we v. you choice.) This is a repeat of an earlier blog post with the same problem of relying on don’t statements, which do not help readers, listeners, or the world.

We know better; let’s do better.