What AI writing will always lack: wit

Real writers have wit. AI doesn’t. And that is unlikely to change.

Christopher S Penn did a fascinating comparison of how an advanced AI tool, GPT-J-6B, completes writing content based on patterns it has digested from massive amounts of source material. His conclusion:

I am bullish on AI creating content at scale.

I am bearish on AI creating GREAT content at scale – or at all.

Chris applies the AI to the start of a press release. It finishes by creating something that sounds a lot like a press release.

Then he applies it to a newsletter by Tom Webster. The result is coherent, but it doesn’t sound like Tom.

There are plenty of reasons why. But the main one is this: Tom is a very witty writer. GPT-J-6B is not, and it and its peers and successors never will be.

What is wit?

Wit is what makes it fun to read nonfiction.

Wit is prose that goes in an unexpected direction. For example, Tom writes about audio and podcasts. Here is some text from Tom’s newsletter:

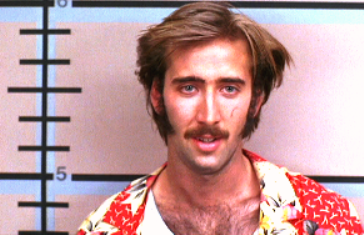

Putting your comedy or fiction or entertainment podcast in between Angry White Dude #4 and Angry White Dude #5 on a Sunday night is like trying to open a Lululemon in the other mall–the one with the Radio Shack and the Spencer’s Gifts and the Orange Julius. It is, to quote the great philosopher H.I. “Hi” McDunnough, a barren place where your seed can find no purchase.

Here’s Jay Acunzo, another witty guy:

. . . . we can’t agree in objective fashion about which is THE BEST film … or THE BEST in any category at all: the best restaurant, the best dish, the best team, the best fashion brand, the best actor, the best city, color, podcast, newsletter, software, accountant … you name it. We can’t agree on what’s best, even though each of us will freely and confidently declare plenty of things we know as “the best” … at least, according to us.

So maybe, when we declare something THE BEST, we aren’t really thinking about what’s best at all. No, I think when most of declare something THE BEST, what we’re really saying is this:

“That … is MY FAVORITE.”

And if that’s true, if your favorite things supersede any other types of things, then we have to rethink how we usually approach our work. Because we spend a shocking amount of time trying to prove to ourselves and to others that we are, in fact, the best. But maybe that’s not possible— nor would it matter to anyone if it did.

I get it. We want to be the best — at our jobs, in our categories, in the minds of those we serve — because we think that’s how to grow our businesses and leave our legacies. We want others to adore our work as a result:

Not just followers. Superfans.

Not just customers. Evangelists.

Not just coworkers. Teammates.

Not just new hires. Difference-makers.

If only they knew we were the best, if only we could make them see, then we’d be hugely successful.

If only they were aware of our greatness.

My point is not that these two writers (or any other writers) are the cleverest writers on the planet. My point is that they do not choose predictable paths. They go in directions that their own minds take them, and those minds are unique. They translate that uniqueness into writing, and when we encounter it as readers, we smile. That’s wit.

Wit is infinitely variable

Seth Godin is witty. Daniel Pink is witty. Malcolm Gladwell is witty.

They are not witty in the same way as each other.

In fact, they are not witty in the same way they were the last time you read them. What makes them witty is that they break the pattern. Not just the pattern of English language writing. Not just the pattern of nonfiction writing. They even break the pattern of their own writing.

I admit, if you give me a passage of Gladwell or Pink or Godin, I could probably guess which one wrote it after a few pages. But I cannot guess where it is going. It is going to surprise me, even as it makes its points.

So if I train an AI on everything Seth Godin writes, it may be able to copy his sentence structure and his frequent use of the word “you” and his one-line paragraphs, but it can’t really be as witty as Seth, because Seth is always going in a direction you don’t quite expect.

So is Daniel. So is Malcolm. So are Jay and Tom. And I hope, so am I.

Putting things simply — we’re not just sharing new content, we’re sharing new ideas, and if we don’t bring you something unexpected every once in a while, we’re not very good writers.

That’s why, as Chris Penn explains, GPT-J-6B is now an actual writer, but will never be a great writer.

Because it lacks wit.

And, at least based on what I’ve learned from everything I’ve seen and read about AI, I cannot see where it could ever get wit.

The AI researcher Janelle Shane tried to teach a neural network AI to tell knock-knock jokes. This is the pinnacle of what it achieved.

Knock Knock

Who’s There?

Ireland

Ireland who?

Ireland you money, butt.

That may be the very tiniest bit funny, but it’s not wit.

If you’re a writer, develop some wit. Readers will like it, and you won’t lose your job to a robot.

Loved this piece. Robots can and will do a lot of things, but the nuances of being human will never be duplicated.

And any article with a deep pull from Raising Arizona is OK with me!

Robots can now write with the proficiency and panache of a corporate human resources department. Yay?

Some people build and train such robots just to see if they can; Frankenstein may have had good intentions. But what benefit is this development supposed to have for the rest of us? Faster production of low-quality “content”?

Josh, your experience as an analyst must have given you some insights. Who puts money behind this kind of research, and how do they expect to get money back out of it later?

Meanwhile, it lacks the wit of your pseudo-AI real estate listings, which I enjoyed sharing, but here’s my favorite example of what happens when you ask a robot to answer something more complex than a yes-or-no question:

https://www.quora.com/What-poverty-food-is-actually-really-delicious/answer/Jeremiah-380?fbclid=IwAR0ZUiInh09DV8zwf_i23yvsyUoUWHfFARW0oLnL9lp3VR7gys2iBrAoE40

p.s. Autocorrect kept changing “wit” to “with,” an indication that robots don’t even recognize the word.