“Turn of Phrase” at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art: Doing violence to text as an art form

I think of words as a medium I can use for the clearest possible communication. So it was very strange to see artists using words as art materials — and often, for the purposes of obscuring communication rather than clarifying it.

Some thoughts on “Turn of Phrase” at Bowdoin College

Bowdoin is in the charming town of Brunswick, Maine, just north of Portland. There’s a small but fascinating art museum attached to and maintained by the college.

From now through June 4, the museum is featuring an exhibit called “Turn of Phrase: Language and Translation in Global Contemporary Art.“

I want to be clear that while I appreciate much of what is beautiful and striking in representational art, I often don’t “get” contemporary art. As an observer, you’re often left wondering what you’re supposed to think. This, I’m sure, marks me as a completely unsophisticated art observer. (It’s also a nice out for the curators of this exhibit, should they stumble upon this post, to say “Ah, he didn’t get an MFA at an accredited art school, therefore, we don’t have to get worked up about his opinion.)

If you wonder what you are to make of this particular exhibit, there is, of course, the obligatory essay book that accompanies it, by the curator, Sabrina Xiyin Lin. She helpfully explains:

Exploring how various artists at once capitalize on language as a subversive strategy as well as challenge language’s limitations through translation, this essay looks at the plural and hybrid ways global contemporary art engages with questions that puzzle, motivate, and inform artistic practice. . . . The exhibition creates an avenue for “seeing” works of art that might appear, at first glance, abstract, abstruse, or inaccessible. By embracing global contemporary art’s myriad voices, narratives, and histories, Turn of Phrase demonstrates the remarkable vibrancy and multiplicity of artistic innovations.

Got it?

Of course, I do have an opinion about just about everything you can do with words, which is why I visited this exhibit with my wife, an artist.

I use words to make art. So do these artists. But their idea of what words can do is pretty different from mine.

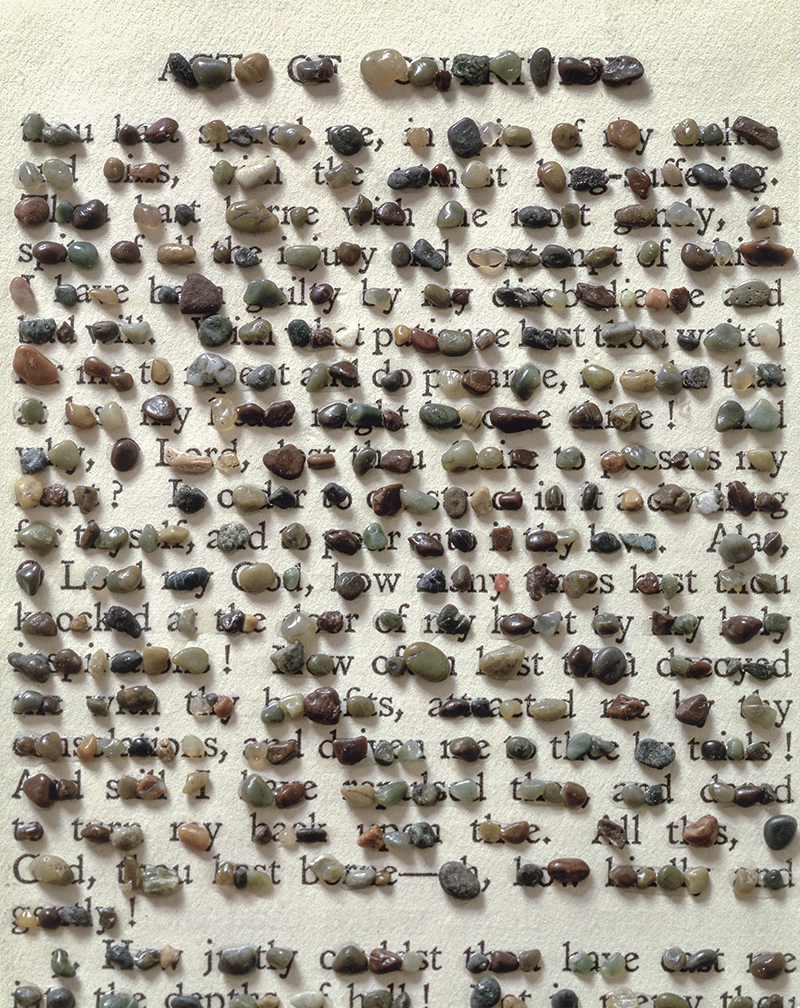

For example, there is a set of book pages that have been adulterated or enhanced with pebbles, in an untitled piece by Ann Hamilton.

You encounter this in a glass case, look at it, and naturally, try to read it, because that’s what you do with book pages. You can look at it from a few feet away and the pebbles communicate something about language and its cadences. But when you get close, the pebbles instead communicate “You want to read this? No. Look at the rocks here. You think there’s meaning here? Well, the meaning is no longer in the words. It is in the pebbles obscuring the words.”

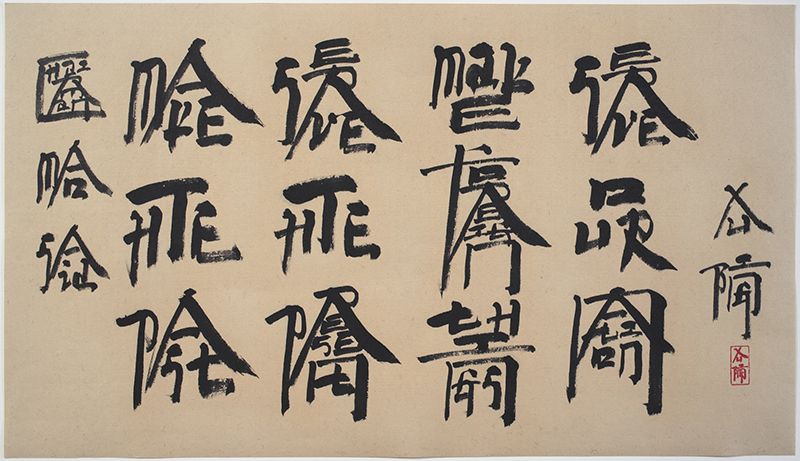

If you don’t read Chinese, you might find this next piece by Xu Bing, a quotation from Chairman Mao, a bit hard to make out. But if you stare at it long enough, and read it vertically, you might be able to see that it’s not actually in Chinese — and in fact, no Mandarin speaker would even recognize the characters unless they understand English as well.

There’s the series of photos of the artist Song Dong who took a wood block carved with the Chinese character for “water” and then slapped the block repeatedly against the water of the Lhasa river for an hour. That’s showing the text who’s boss.

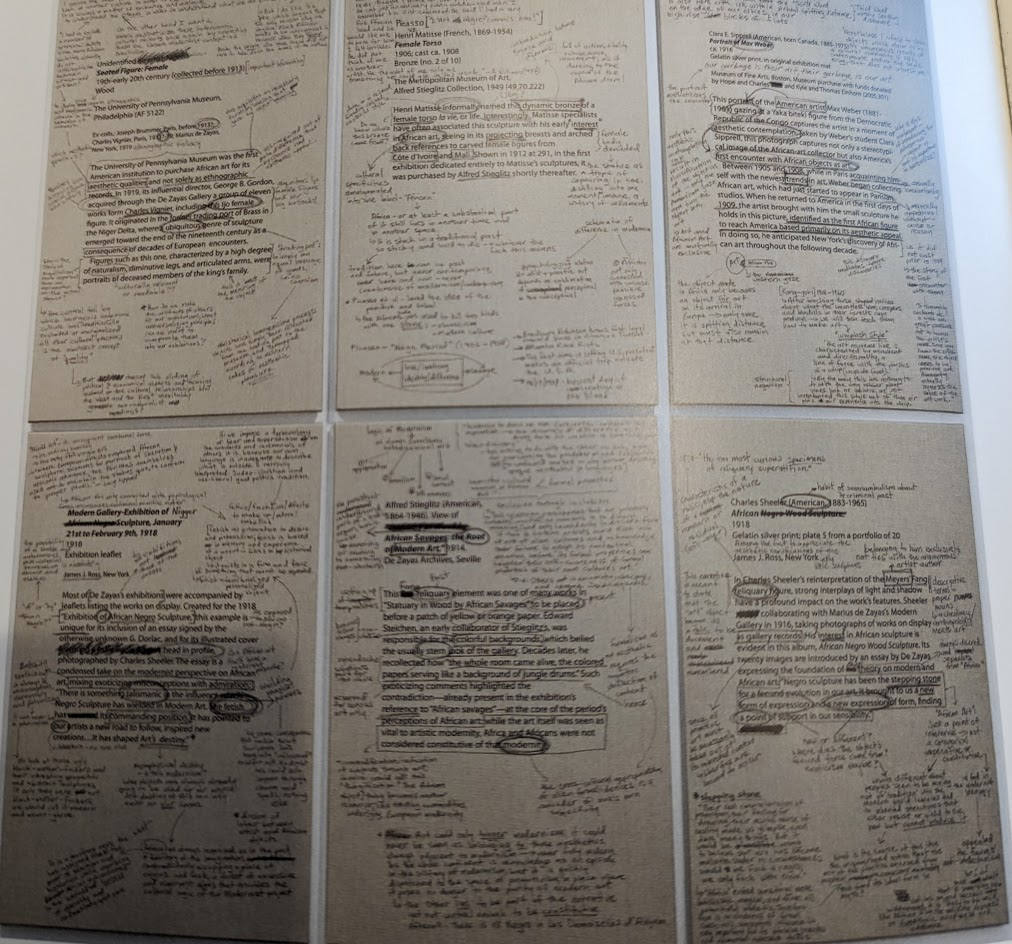

But my favorite piece here is an enlarged set of those little information placards that you see next pieces of art, but in this case, the artist, Meleko Mokgosi, has elected to provide his own notes on the placards revealing the deep ethnocentrism of the museum curators as they describe native art pieces from their narrow and biased perspective.

This piece, of course, was attached the wall and accompanied by its own explanatory placard, which I somehow restrained myself from what I felt would be the normal reaction, which is to graffiti all over it. (There’s actually another piece in the exhibit with a pencil attached nearby where you are invited to write your impressions on the wall, I suppose so that you don’t feel the urge to do what Mokgosi has done to these placards.)

In case you’re still not “getting” it, Lin explains everything in her own commentary on this piece:

Meleko Mokgosi’s Modern Art: The Root of African Savages (2013) calls out the canon of Western art as constructed through the process of systematic, exploitative Othering. . . . Mokgosi employs the polyptych-like format to underscore the functionality of text. The association between an artwork and its description is disrupted to emphasize the objecthood of descriptive language, something manually created, intentionally produced, and belonging to a particular space and time. As a form of representation, the panels seemingly share an official, institutional “look” in their overall style, length, typefaces, and graphic designer. The viewer, reading through the labels’ content, is either quickly taken aback by the presence of outdated, offensive terminologies, or prompted to reconsider words that might have initially appeared familiar and acceptable. . . . By contrast, Mokgosi’s own inserted text ranges from sharply analytical to vehemently personal, not shying away from foul language or satire and being explicitly emphatic in the artists’ subjective voice. . . .

By targeting museum labels as a particular mode of superimposing and dispersing meaning, Mokgosi also challenges the limits of representing through text, “always [having] human history in the form of the linguistic wall label, thoroughly taking over the art object.”

I find it amusing that this since Lin probably wrote the wall labels for all of these pieces, curators like her are presumably the target of Mokgosi’s critique. (“But my wall labels are not racist and ethnocentric like the ones he scribbled on,” I can imagine her saying.)

The wall labels that Mokgosi scribbled on are actually a lot clearer than the ones you typically read in a contemporary art exhibit — they may be racist, but they’re not obscure and full of jargon. My own urge to adulterate wall labels is more about the obfuscatory art-historian language they use; my reaction may not be as significant as Mokgosi’s, but it’s just as heartfelt.

Last words

For me, words are a medium. I don’t care if you read them on a screen, listen to them in an audiobook, or curl up with a printed book and read it — they’re going to create ideas and pictures in your mind, and that’s my goal.

For these artists, words are clay from which concepts are created. If you can just read the words, that’s insufficient. That’s not art, it’s literature. As a creator of words, I feel like you’re supposed to just accept what I create in the form I created it, but these artists don’t accept that. They’ll take the physicality of words and turn it into their own art form.

You can let that wash over you, or you can read the wall label and puzzle over the nice unadulterated but probably opaque words written there. Just don’t write on the wall labels — it’s a museum, and you have to behave nicely to the people who collected these transgressive artists and put their work where you could see it.

To paraphrase a quotation ascribed to Lincoln, Lin can compress many words into few thoughts. https://quoteinvestigator.com/2020/03/30/compress/

” …they may be racist, but they’re not obscure and full of jargon.” !!!