To write well and efficiently, choose the right level of editing

Editing is like going to the dentist — nobody likes it, but you’ll avoid a lot of pain and ugliness if you get the right help at the right time. And you need to pick the right intensity of editing to match what your writing needs; you can’t fix a toothache with just a cleaning.

Editing is like going to the dentist — nobody likes it, but you’ll avoid a lot of pain and ugliness if you get the right help at the right time. And you need to pick the right intensity of editing to match what your writing needs; you can’t fix a toothache with just a cleaning.

Good writers can write bad stuff. Here’s why:

- They didn’t get an editor.

- They didn’t listen to their editor.

- They got the wrong kind of edit at the wrong point the process.

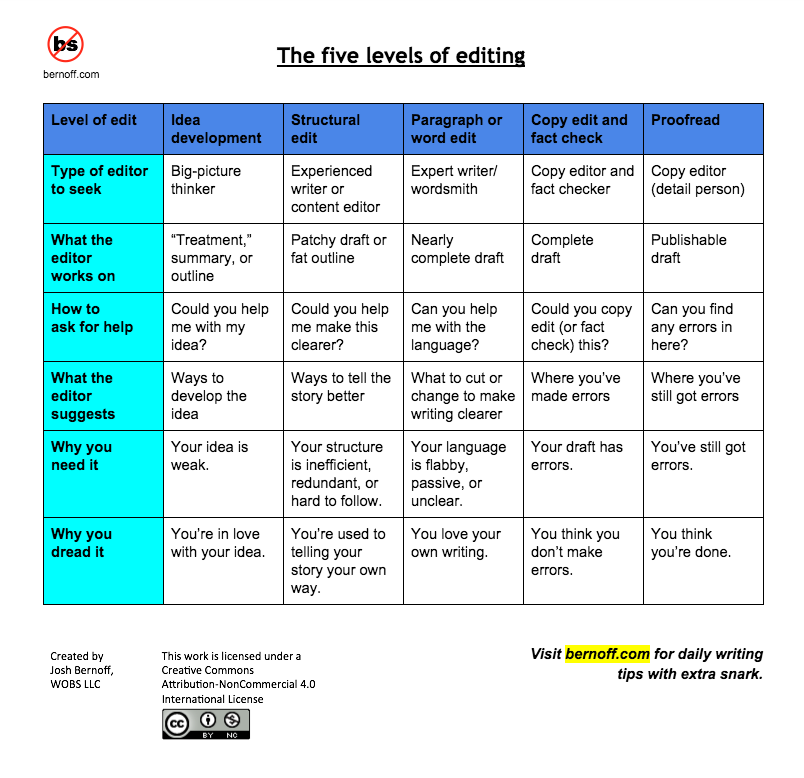

Editing is coaching. It’s criticism intended to make you better. And it applies to all kinds of advice about a piece, not just which words to change. In my experience, there are five levels of edits, from spitballing big conceptual ideas to correcting nit-picky details. (My perspective is more nuanced than many professional editors, who only discuss three or four levels of edit.) Apply these distinctions carefully when working on a non-fiction piece of at least 5,000 words. On shorter pieces, you can combine some levels.

Let’s go through the five levels quickly. (As usual, I’ve created a wall-chart to summarize all this at the end).

Idea development

Before you start, you need an idea. Then you need some pushback on your idea. This is idea development, and it was my job for the last five years at Forrester Research. You need someone who can tell you if your idea is amazing, trite, or weak and how you might improve it. Fixing the idea before you write can save you from wasting huge amounts of time.

Take the time to write a “treatment” of your idea: a summary, less than one page long, of what you will write. Find a person or two who are great with ideas and beg them to bat around the idea for 30 or 45 minutes. Remember, you don’t have to take their suggestions, but you owe it to yourself to make the piece stronger by addressing their concerns.

Structural edit

Some writers try to write from beginning to end and find themselves stuck with a bad structure or storyline. Others stitch pieces together and wonder how to make it all fit. We all end up with wonky structures and insecurity. This is where you need a structural (or developmental) editor. They’ll be most useful if you’ve got a full draft with some holes, but can also work with an outline that’s got some meat on the bones (also known as a “fat outline“).

Structural editing shouldn’t scare you; it just means rearranging and combining your ideas. But it does require you to tell the story differently from how you’ve been thinking about it. Restructuring a piece once or twice, regardless of the reason, inevitably makes it better because it gives you a new perspective.

Repeat this stage until the story hangs together well.

Paragraph or word edit

Once the story works, write it. Since you’re not perfect, you’ll have some parts that sound great and other parts full of bloated sentences, passive voice, and other flaws. This is where you need an expert writer/editor to apply the ten top writing tips.

Most of good paragraph- and word-editing is cutting. Get used to seeing lots of red ink or markup. The best editor at Forrester was the late Bill Bluestein. When Bill thought enough of your draft to cover it with red ink, you knew you were on your way to a good report.

Asking for word edits on a fragmentary, incomplete draft is a waste of time. That incomplete draft is going to change a lot before you’ve completed it. Those word edits will apply to language that you’ll delete or rearrange, making them worthless.

Copy edit and fact check

The draft is done. Sort of. But you know it’s not perfect. You need copy edits and fact checks.

Copy editing is a specialized skill. Copy editors can read anything and spot the inconsistencies, grammatical errors, and embarrassing language. They’re a breed apart: they love perfection and finding little errors. Bad copy editors remove the life from language. Fight them. Good copy editors save you from your flaws. Reward them (preferably with chocolate).

Fact checking happens around this time too. It’s when you make sure that if you say there are 3 billion Internet users, you’re not just making it up. This is a great job for an associate level staffer who can check and make sure you’re not making a fool of yourself or inviting a lawsuit.

Proofread

Every change you make has the potential to introduce another error. The proofread stage is where you catch those little errors. You can dispense with this stage (or shrink it down to nothing) if you’ve got a short piece and trust the copy editor.

—

Embrace criticism. But even more importantly, choose the right editor who can provide the right level of edits at each stage. Efficient writers have learned this habit; you should, too.

Photo: Red Ink Editing and Design

Photo: Red Ink Editing and Design

For most of my writing life I would have chosen dental work over editing. It helped that I had a really cute dentist.

But my time at Forrester forced me to get over that. It also taught me that word edits on a “fragmentary, incomplete draft” are NOT a waste of time. Word edits force me to clarify my thinking, which often leads to a structural revision. Countless times I’ve seen a beautifully edited sentence or paragraph and realized “shoot, that’s not what I meant at all. So what did I REALLY mean?”

Elsewhere on your site, you say you believe good ideas are synonymous with good writing (forgive the vague reference; I’m unable to find it again). I completely agree. But it doesn’t go both ways—great writing doesn’t mean the idea is sound. Sometimes, you can only see the holes in the idea when the writing is polished.

Of course you’ll delete or rearrange language and lose many of your editor’s painstaking word edits. But those edits weren’t without value.

Wonderful post! As an editor, I can attest to chocolate being a good reward. 🙂