The truth vs. the story: How not to report an earthquake

Jonathan Katz was a wire reporter in Haiti when the earthquake hit in 2010. In a fascinating piece in the New York Times, he explains how reporters covering a natural disaster — like the recent earthquake in Nepal — follow a script determined by what they have access to, rather than what’s actually happening.

This script includes underreporting the rescue actions of local people, the arrival of heroic search and rescue teams, the miracle rescue of the late survivor, the desperate looting, the person who could have predicted it, and of course the threat of disease and infections from poor sanitation and dead bodies. Sound familiar? But as Katz points out, reporters in a disaster zone often find what they’re looking for:

As for the notion of post-disaster disease outbreaks, epidemiologists have gone looking for evidence of epidemics resulting from calamities like earthquakes, and they have generally concluded that they don’t happen. (“The news industry is prone to emphasizing more dramatic and simplistic messages, and unjustified warnings will likely continue to be spread on the basis of an approximate assessment of risks,” the authors of a 2006 study wrote in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.) If you look closely, news reports tend to cite unspecified “fears” or “threats” of disease, often sourced to nongovernmental organizations like the Red Cross. But those sources are rarely asked to produce any actual evidence.

NPR’s Brooke Gladstone’s reveals the truth in an interview with Katz. Click to listen.

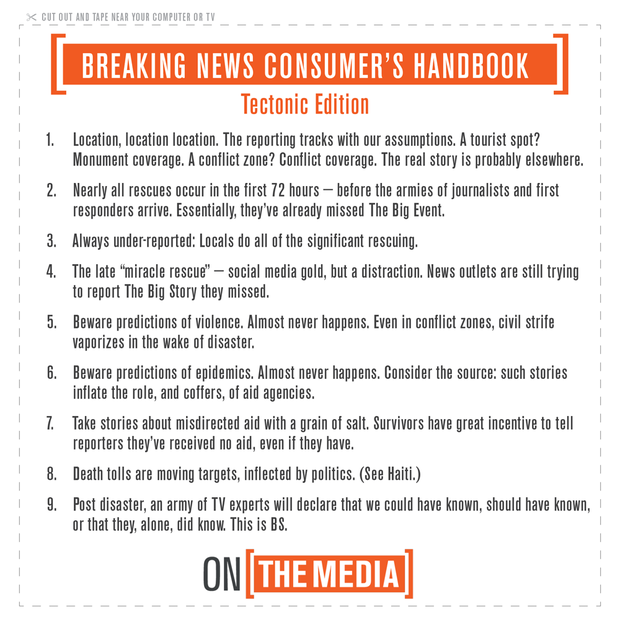

Graphic: NPR.