The Trump Twitter ruling affirms the right to troll public figures

An appeals court affirmed a ruling that Donald Trump’s Twitter account can’t block people. Let’s take a look at what that means.

First question: is Trump’s account a part of the public record of government or an activity undertaken by a private citizen? It’s clear from what he posts that it’s intended to public activity. Just choosing at random, this morning’s tweets included commentary on the Steele dossier, clips from Fox News, and politicking on the case of the citizenship question on the census and calls for boycotts. This is politics from the President of the United States. Putting aside the question of whether it is appropriate, it is certainly part of Trump’s political, and therefore official, communication.

Government communication falls into two classes: public and secret. All of the government’s public activity is completely out in the open, and all members of the public must have equal access to it. (Did you know that there is no copyright on any government content? That’s because we, the citizens, own it, not the government — after all, we paid for it.)

This is the broad argument for not allowing Trump to block people.

But let’s go a little farther with this. Even if you are blocked, you can still see Donald Trump’s tweets. You can’t view them in the Twitter app or if you are logged in to Twitter.com on your device, but you can log out of Twitter or go into incognito mode on your browser and visit https://twitter.com/realdonaldtrump. So you are not really “blocked” from seeing Trump’s tweets.

Or, you could just create a new Twitter account and view them from that account.

You are, however, prevented from interacting with them with your blocked Twitter identity.

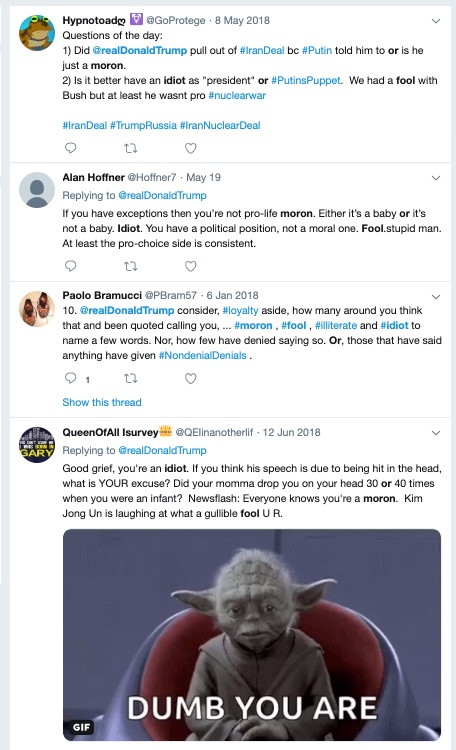

So what the appeals court is actually saying is that all citizens — all Twitter users — are free to interact with Trump’s account. They can reply. They can retweet with a comment. They can like. They can mention Trump’s handle in their tweets and have those tweets show up in his list of mentions. They have freedom to troll Trump if they wish. They can claim he has sex with underage sea otters in a reply to a Trump tweet. And all he can do is report them to Twitter in the hopes that they’ll be perceived as violating Twitter’s terms of service.

The appeals court says that trolling public figures on their official or quasi-official accounts is protected speech.

I think this makes sense, but let’s be sure what we’re getting into here.

A user, Dov Hikind, has sued Democratic Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez for doing just what Trump did: blocking people from her official Twitter. And logically, AOC’s Twitter feed is just as much a public record as Trump’s. So she shouldn’t be able to block people either.

A look at AOC’s replies shows people calling her a monster, a bitch, and much, much worse. Her trolls are less numerous than Trump’s but, since she is a woman, they’re nastier.

Is this protected speech?

I guess it is.

Trolling is now protected by the constitution. Just don’t threaten violence and you’re on solid ground.

Free speech is ugly. Government figures are targets. That’s how it works.

If you don’t like this — and it’s certainly unpleasant — I look forward to hearing your solution.

I would like to hear your comments on the nature of trolling however. Some trolls are enguaged in outright slander and defamation of character. I don’t know if that really falls into the area of “freedom of speech” … certainly not civility or good taste.

I’d like to hear your analysis of where the line is drawn between free speech and slander.

The problem is not the definition of slander (or libel — is a tweet a publication or speech?). That’s clear. Slander of a public figure is false and harmful statements uttered with malice, either if the person who makes them knows they are false or is in reckless disregard of the truth. These are public figures we’re talking about, and that definition applies in a lawsuit.

There are plenty of statements like that made on Twitter.

The challenge is enforcement. Based on this ruling, they can’t block the person. If they sue, they need to find out the person’s actual name, which may be difficult. Probably too expensive to pursue. And if they complain to Twitter, unless there is a threat or hate speech, Twitter won’t remove the person’s account. So the number of avenues to deal with slander/libel is now quite limited.