The simple truth about writing a business book

There’s a simple, ironclad chain of logic that tells you everything you need to know about writing a business book.

Start with why. Why are you taking on the challenge? It’s going to take a lot of your time and effort. It will require an incredible commitment of creativity and energy. So why bother?

The only realistic reason to write a business book is to boost your own business. It’s a major effort to produce a book – you don’t have time to do this just for fun. Unless you are very lucky, you won’t get rich off of the sales. Sure, it will help you get speaking gigs, but in the end, the justification to write a business book looks like this:

- People – most notably your customers – will read the book. Even if they don’t read it, they will notice that it exists.

- The book will create the impression that you are an expert in your field with valuable insights for those customers.

- Customers will learn from the book and adopt your mindset.

- This will make it easier for you to close business with these customers. Customers who perceive you as a credible expert and who have adopted your mindset are ready to work with you.

From this perspective, a business book is basically a big lump of content marketing. Content attracts customers and makes them ready to work with you.

What this means for audience and content

As with any writing, start with your audience. In the case of a business book, your audience is decision-makers who are interested in your products or services. There are secondary audiences, like critics, analysts, bloggers, podcasters, investors, and “influencers,” but they’ll evaluate the book from the perspective of the business decision-makers.

Why are the decision-makers reading your book? Because they have a problem. Your book should help them frame and then solve the problem. Notice the two words “help them.” The purpose of your book is to help. If you can help your audience, the book will be a success. To the extent that you stray from helping them, your book, and your efforts associated with it, will fail.

For example, is your book is a book on sales strategy, your audience is salespeople, and your job in the book is to help salespeople to sell better.

The formula is simple. But the discipline it requires is not. This means you should not spend time or words in the book talking about how great you are, your incredible experiences, or how superior your product is. None of these things will help your audience to succeed.

On the other hand, time and words that are valuable to the audience include defining the problem, describing the problem, explaining the solution, laying out elements of the solution, and advising the audience how to implement that solution. The more of this you do, and the more effectively you do it, the more valuable the book will be to the readers, and the more it will impress your potential customers.

The structure of business books

The purpose and content that I just described dictates a particular structure for any given business book.

Chapter 1 is the scare-the-crap-out-of-you chapter. Anyone reading Chapter 1 should have experience either fear or greed. For example, a fear chapter might say if I don’t change the way I safeguard data, I will suffer data breaches and lose my job. A greed chapter could say that if I properly adopt artificial intelligence, I will save costs and improve my approach to customers. (These are not exclusive – you can often generate fear and greed together.) Either way, at the end of Chapter 1, you lay out a brief description of your solution as a nugget of hope for the reader. This primes the reader for what follows.

The next few chapters should lay out the elements of the solution. You define your terms, describe your process, and build the structure of your solution. If you have done your job well, then once the reader has read this, they will think “Ah, I see the outlines of what I need to do here, and it is quite convincing.”

The remaining chapters lay out the solution in detail. For example, you may have a chapter for each step in a process, or a chapter for how this applies to different industries such as retail or pharmaceuticals.

Finally, since your idea is so powerful, the last chapter should reflect a view of what will come next. For example, you might show a view of the future after many people have adopted your solution, or a description of how it will change the customer’s life.

How to write and structure a chapter

Every chapter in the business book has a job to do. If it is the first chapter, its job is to scare the crap out of you. Other chapters may be about a specific element of a solution, or how to gather support among executives, or just about any other element of the topic you’re describing. But the point is, each chapter has a job to do.

You should be able to write that chapter to fulfill an objective for the reader.

Here are some examples:

After reading this chapter, readers will know how social media is helpful in customer service and how to set up a social customer service program.

After reading this chapter, readers will understand the five types of corporate data and how to catalogue them in preparation for generating value from them.

After reading this chapter, readers will know how to organize their email inbox to improve their time effectiveness by 20%.

If you are writing a chapter, you must keep this objective in mind at all times.

The other thing to remember is that book chapters are narratives. They are stories. That means they have threads, which are reflected in the sections within the chapter. For example, here are some story threads.

Passive voice makes business writing muddy. Here’s what passive voice is. Here are some example of how it causes problems. Here’s how to recognize it in your own writing. Here’s how to change your passive voice habit. Here’s how to rewrite passive sentences.

Each of those sentences is a section.

It’s great to start a chapter with a case study, since case studies involve the reader. But soon after the case study, you need to get on with explaining the moral of the case study, followed by sections in a logical sequence.

Within each section, you need to be consistent. If the section is about a concept, explain the concept. If the section is about a series of steps, show the steps with examples. If the section is about how to measure the results, concentrate on measurement. The reader can follow what is going on because the sections connect in a logical sequence. In fact, at the end of each section, you should include a sentence connecting it to the next section (unless the connection is obvious).

Avoid going off on tangents. Remember, the reader is there to understand what to do. They have very little patience for extended soliloquies on other topics. They don’t want to be impressed by your brilliance and encyclopedic knowledge of the topic. The way to impress them is to use that knowledge to focus them on the most essential elements of the topic. If you feel there are more details that must be in the chapter, put them aside in a table or sidebar.

Once you have organized the material, you can write the chapter. Just deploy the elements and connect them with prose. (I know, easier said than done, but it’s a lot easier to write with all that material assembled and organized.) If you keep the objective in mind, you can related each of the sections to that objective. Then, once you get to the end of the chapter, you will have proven your points and helped the reader to accomplish that objective.

But, but, but . . .

You may think what I have written here for instructions is too rigid and simplistic. You’re saying “But I want to do this differently . . . ” So let’s take a look at your objections.

But I want to write my story. Good for you. If your story is incredibly fascinating . . . if you were the first woman to start a billion-dollar company, or the guy who solved Fermat’s Last Theorem, maybe we wan to hear your story. But for most people, the story of your career is not enough. You’ll have to boost its value by drawing lessons for the reader. Those lessons will drive what you write. And you’re back to “I want to help people” and an objective for each chapter.

But my book is a big idea book. That’s great. People love big ideas. Big ideas move people. So write about the big idea in chapter one. Then write about why the idea is true. And a big idea is not interesting unless it suggests that readers do things differently in view of the big idea. You’re back to “I want to help people” and an objective for each chapter again.

But my book is a manifesto. Good for you. Shake things up. But let’s be honest. You wrote this manifesto to change things. Changing things demands that you move people. Having moved them, now you have to tell them what to do. Objectives again.

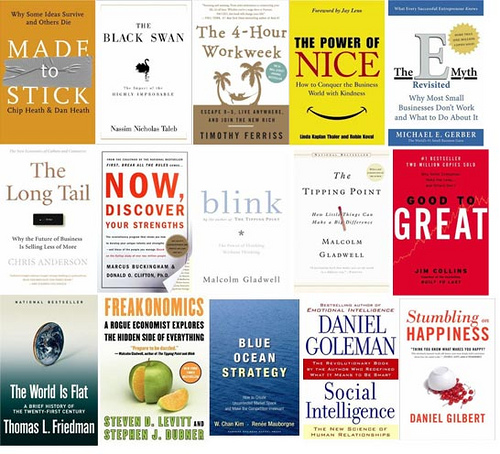

But I just want to tell people what I know. How self-indulgent of you. Unless you are a storyteller as talented as Malcolm Gladwell, people won’t read your book and they won’t share it. If you’re an academic, this might be enough for you, but if your objective is to boost your reputation, your book will fail.

Go ahead. Disagree with me in the comments. Tell me your “But I” statement if you want.

Or, you could just get to work trying to change how people think and help them. That’s probably a better way to get started.

I’m no Gladwell when it comes to storytelling, but I’m completely with your here:

It’s great to start a chapter with a case study, since case studies involve the reader. But soon after the case study, you need to get on with explaining the moral of the case study, followed by sections in a logical sequence.

Stories resonate with people. I also in my books like to take a step back after my case studies. What can organizations learn from the ones that I just profiled? Ideally, this educates the reader and demystifies the process, whether that’s using Big Data to make decisions, adopting truly collaborative tools in lieu of email, etc.

1. I love how direct and to the point this article is and agree completely with the premise. 2. The points are clear and prescriptive and are making me feel MUCH better about the book I just finished…particularly my heavy -handed fear-mongering first chapter. 3. Fermat’s Enigma is my very favourite book. I had to smile when you referenced “the guy who solved Fermat’s last theorem.”

Thanks! I will use this with my students to help them understand when I talk about having a purpose when they write.

Great article.. I have a few self help books on KDP Select that literally make a few dollars, lol. I attempted a full blown novel with the help of a ghost writer a while back, took just over a year to complete… managed to sell a few copies lol. I sort of realized half way through the project that it probably wasn’t going to do that well, but by then I had this stubborn urge to finish it… Haha, anyways I got some good points from your post, Cheers

Hi Josh, although we met years ago at various CMC events (btw, I’m now living in Boston full-time), and you gave me a copy of your book, I’ve been totally missing out on your blog until this week when it popped up in a Google search, and now I’ve been devouring it since my full-time gig is now to help entrepreneurs self-publish a nonfiction book to help them grow their business. I’m already quoting you and linking to your blog in the workbook I’m finishing up for my membership group. This post is just another example of the great stuff I’m finding on your site. Thanks again!