The Rationalist Papers (8): Back to normal

My son Ray, a recent college graduate, is interviewing for jobs right now. In a conversation at the dinner table, he described how surreal the experience seems. Not only must he do all the interviews by video, but there’s the nagging question of whether a normal entry-level job for a normal company will even matter.

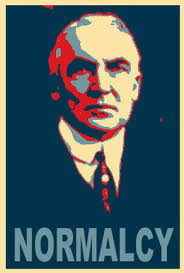

The subtext here is the unspoken question of what world he (and all of the rest of us) will inhabit. We’re worried that the next guy on the subway could transmit a deadly disease. We have a president who seems to make up his own reality, and a challenger who appears to be a time traveler from many decades ago. Racial upheaval is happening, with peaceful protests punctuated by occasional violent and deadly actions from extremists. The economy, built for a “normal” world, is making a rough adjustment to the new abnormal, throwing millions out of work. And somewhere in the middle distance, the planet is heating up, coasts are flooding, and acres of open space are on fire.

Concepts like content marketing, market research, copywriting, and video production — traditional entry-level jobs for many college graduates — seem somehow trivial when the fate of the world seems to hang in the balance. Will these companies that sell kitchen equipment, lawnmowers, marketing services, or whatever still have a role in whatever future might emerge from this hellscape?

Thinking about the government’s role

Ray’s question made me think very hard about how stuff is supposed to work. Having been around for more than 60 years, I’ve seen my share of jobs, transitions, politicians, and crises. What happens in America when stuff goes wrong?

Politicians are always talking about “job creation.” But politicians don’t create jobs — and governments shouldn’t. The government’s job is to make sure that there is an environment in which we can worry about doing regular jobs, rather than about everything else.

If I get in my car and drive to the store, I don’t worry that the traffic light will suddenly turn green in both directions and lead to a collision. I don’t worry that the car’s wheels will fall off. I don’t worry about the safety of the meat or the vegetables in the supermarket. When I pay with a credit card, I know the financial system will safeguard the transaction, and that my bank account will still be there — and still be worth pretty close to the same amount — as it was when I put the money in the bank.

I know that if somebody sends me a package or a check, it will arrive in my mailbox in a reasonable period of time.

I know that the doctor I go to earned a legitimate medical degree and that the drugs that she prescribes are safe and effective. I know that if I get cancer, my medical insurance will allow me to get appropriate treatment — the same treatment, with the same quality, available to anybody else.

These, of course, are ordinary things I depend on the government to do in ordinary times. I can worry about my actual job as a freelancer helping authors and corporations and not worry about the safety and security of the world I work in — or of my clients’ worlds. This is why they can concentrate on what I’m trying to help them with, rather than whether their children are safe or their company is about to become irrelevant.

What about when there’s a crisis?

In ordinary times, Ray would only be worried about the usual things when interviewing — is it a good company, how’s the pay, did he make a good impression? But these are not ordinary times.

So what does the government do in extraordinary times?

It takes bold and extraordinary measures to bring back what we think of as the American way of doing things.

I remember when 9-11 happened. Air travel stopped — then started up again, under new rules intended to keep us safer. And we went to war to try to fight against the enemies who had attacked us.

I remember the financial crisis of 2008, brought on by the collapse of Lehman Brothers. The administration of George W. Bush took decisive action and the Congress passed a bailout bill to restore faith in the economy. As Barack Obama took office, his team continued and extended those actions. Democrats and Republicans took their responsibilities seriously; both supported the recovery. The recovery allowed people to return to work, to have faith once again in their investments, and to return to a world where ordinary companies could do ordinary things.

When there is a hurricane or an earthquake, we send FEMA. We help people rebuild. In cases where that help is not enough — as with George W. Bush’s handling of hurricane Katrina — it is shocking, because we expect government to fix things like that.

In order for Ray to win that job and have some hope of building the normal life of a college graduate, he needs to have faith that the government will do what it must to pull us out of the jaws of these crises. We need a plan to slow the spread of coronavirus, and ensure that a vaccine is safe, effective, and available. We need a plan to rebuild the decimated economy. And we need to have faith once again that the government will function as it is designed to do, even though there are people in it with different ideas about how to solve the problem.

What is the best way to solve these problems? That’s a difficult question. But a president is supposed to have access to the smartest thinkers on these topics — public health officials, economists, and congressional liaisons, for example. And that president is supposed to get all the accurate facts from some people — good news or bad, with a diversity of opinions — and then make decisions on how to create a normal way of life again.

These are not Democratic or Republican values. This perspective represents a common view of American government. It has worked through all the crises of my lifetime, from Cuban missiles to planes crashing into buildings to financial meltdowns.

When I vote in November, that’s the beginning of what I’m looking for: a plan to solve problems and get us back to doing decent work for decent pay, without worrying about the fate of the nation and the planet every hour of every day. For Ray, thought, that’s not enough. He’s looking to find not just a return to normalcy, but a way to begin to change the world to be a little more humane and not quite so greedy.

We now have quite a bit of data about how these candidates handle crises. We have watched one of them tell us that the virus would just go away, that untested treatments would cure it, and that it’s behind us. We have watched the government seize up and the post office slow down. None of this is helping people in pain.

Government needs to use its immense resources to deal with crises too big to handle any other way. Then we can get back to work. Who is going to make that possible?

You have made me think about the term “social contract”. When the Black Lives Matter movement started, Trevor Noah had a small bit on how it was not working for everybody and this seems to be the case in the United States, not just with people of African descent, but with everybody.

I am following your texts on the issue closely, they make me think and I am finding them very interesting, far from the shouting of almost everybody else. Thank you.

Thoughtful essay, Josh; I have three “Ray’s” of my own and I’ve been thinking a lot lately about our generation’s failure to leave to them a kinder America.

One suggestion for the undecided’s, consider supporting the candidate who first invites us to sacrifice something, indeed anything, for our planet and those most deserving a helping hand.