The Internet Archive is ripping off authors to create its “Internet Emergency Library”

In response to the global pandemic, the Internet Archive is making 1.4 million books available for free until June 30, or until the end of our “national emergency.” Sounds great. Unless you’re an author, in which case this is simple smash-and-grab raid on your copyright.

Let’s get a few facts straight here.

First off, many of the books in the Internet Archive are out of copyright, in the public domain. You can go to the “National Emergency Library” and check out a copy of Moby-Dick, if you think tales of being shut into an unhealthy environment on a dangerous and fruitless quest will help you cope right now. (“Hast seen the white roll?” I can imagine Captain Ahab shouting.)

But many of the books are still in copyright and in control of the publisher.

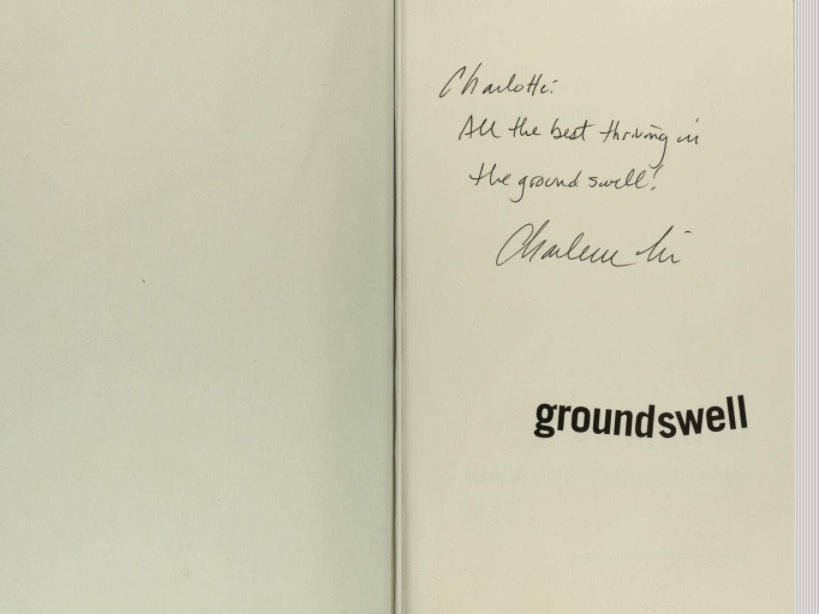

One of them is mine. It’s Groundswell, the book I wrote with Charlene Li in 2008. In case you’re wondering, people are still buying that book and I am still receiving royalties for it. But you can now read it for free. Here’s a snapshot of a page from the Internet Archive’s copy:

How did they get this book? Well, apparently, Charlene gave a copy to somebody named Charlotte. It’s possible that Charlotte gave it to the San Francisco Public Library, and “friendsofthesanfranciscopubliclibrary” gave it to the Internet Archive. And they just made it free to read for anyone who wants to provide an email address.

Do I care that you can read it for free? Not really. But I do care that the Internet Archive feels it has the right to take this book and thousands of others and give them away, although it has no permission to do so.

Jill Lepore of The New Yorker says “The National Emergency Library is a Gift to Readers Everywhere.” Cool. Well then why does The New Yorker limit my access to that article? Shouldn’t it be “a gift to readers everywhere?”

Libraries will loan you ebooks

Wait, you may be thinking. Can’t libraries loan out ebooks?

They can. They pay the publishers for the books, at prices from $20 to $75. They then have rights to allow readers to borrow the book, typically one reader at a time. For popular books, there can be a waiting list, especially if the library has not bought multiple copies.

You may not like this system. Personally, I think it replicates the physical limitations of print books, and it could be a lot smoother and cheaper. But it’s the system we have, and if libraries want cheaper access, they can lobby for it — or even for a change in copyright law.

If you don’t like the system, change the system. That’s not the same as, if you don’t like the system, just steal stuff.

The Internet Archive is behaving like a pirate

The Internet Archive does not go through the legitimate library system. It has simply digitized books (or gained access to digitized copies) and made them available for free to anyone who wants to borrow them.

The publisher gets nothing. The author gets nothing. The reader gets free access to content.

If you’re not an author, you may have no objection to this. Let’s examine some of the arguments you may cite for why the Internet Archive’s actions are not a problem:

- Authors don’t make money from book sales. Well, actually, we often do. It’s up to us to determine who has the rights to publish and buy our books. That’s why it’s called copyright.

- Authors make so much money from books that it doesn’t matter if some copies aren’t paid for. Not really. For a lot of us, thousands or tens of thousands of dollars are at stake. For others, it’s millions. And it’s still our right to determine who can publish and read our books. They belong to us, not everybody — at least until the copyright expires.

- It’s an emergency. Okay, so being that it’s an emergency, should groceries be free? Should you be able to just use my car without my permission? What is it about this emergency that enables you to free access to books outside the legitimate library system? Is your need for entertainment an emergency?

- What if it’s a school textbook? So wait, textbook authors don’t have rights, but other authors do? I think textbook publishers are among the slimiest companies on the planet — but that doesn’t mean you get to rip off the authors and publishers without some sort of permission. If Trump wants to make an emergency declaration that textbooks should be free, let him. Until he does, you don’t have the right to rip off authors and publishers just because your kids are at home. Want to start a GoFundMe for ebooks for kids home from school? I’ll contribute. But that will be my choice.

- This will be up in June. Sure it will. Right. I still don’t like the precedent. For every person who’s in desperate need of a book — say, a college student — there are many others who are just using this as a free way to get books they’d otherwise have to pay for. You think your access to Fifty Shades of Grey is an emergency?

- It’s fair use. That’s the argument that lawyer Kyle K. Courtney makes. But fair use typically applies to small excerpts, not an entire book. Fair use is a red herring. This is just theft — there’s nothing fair about it.

- The Internet Archive is a nonprofit. That it is. And Random House, Amazon, and I are not nonprofits — we’re all trying to make a living here. I must have missed the part where nonprofits can take any action they want with respect to content because they don’t profit from it. It’s still stealing.

Many things are different now. You can’t go to a restaurant. You can’t have a party. You can’t hug your mom. It’s very sad. And there are a lot of awful new rules coming, rules that restrict freedoms and hurt some people in the interests of minimizing the harm to our whole society.

Nobody will die if they can’t get my books for free. Let ’em read Moby-Dick. A global pandemic is not an excuse for systematic stealing of content — or anything else.

Your argument is very persuasive. In fact, I was persuaded of it long ago. It also, arguably, applies to our time, which is taken without our consent, in the form of taxes. And to property, which can be seized in the name of public good. And to our livelihoods, which can also (obviously) be shut down in the name public health. But what is theoretically right sometimes must bow to a practical necessity or at least desirability. Hence, I pay taxes and, as you suggest, try to change the system by which they are taken and redistributed. But those analogies as break down in some way or another. But the question remains: is your copyright something that should bow to a practical necessity or desirability? It’s obviously not necessary, as they can always read Moby Dick (or eat cake). Authors with copyrights should have been asked for permission before the Internet Archive did this. Most probably would have given permission for the limited duration.

What a stupid and rotten thing for the Internet Archive to do. This is not a favor to readers; this is another nail in the coffin of writers being able to make a living. The problem with these dim-witted copyleftists is that they only steal from people who are easy to steal from: writers, artists, and musicians.

You can’t walk into a store and walk out with whatever you want, just because you want it. So they don’t try that. They sit behind their keyboards and steal other’s people’s work because they can get away with it, even though it’s clearly illegal. That simple distinction seems lost on these idiots.

it’s for 3 months….you cannot be serious

Why is it ok to steal what is not yours for three months? Stealing is stealing.

“You can’t walk into a store and walk out with whatever you want, just because you want it.”

Sure you can.

I agree with your argument, though.

Not disagreeing with the arguments here, but do want to raise the point that, although the number of concurrent loans is now no longer one, these are still drm-protected and time-limited loans. It is not the same as “just download this pdf here and it is yours forever.” But yes, this is an odd precedent at best and a bad one at worst.

Also, the Internet Archive has posted their response to the outcry: https://blog.archive.org/2020/03/30/internet-archive-responds-why-we-released-the-national-emergency-library/

What did the Internet Archive say when you reached out to them to request they take down your book — or when you asked them for an explanation of how it is that your copyrighted book got uploaded to their collection? Or did you just decide you knew their intent and motivation and are ranting about it without looking into anything or simply trying to have your book removed? I never would have heard of you or your book without the Internet Archive and now that I have, well…..this will be the bitter taste you’ve left behind.

I haven’t asked to have it taken down; as I said, I don’t care.

And they will take down any book that asks for it.

Does that make it ok?

Why is it my job to ask for it to be taken down? Why do I have to opt out, rather than them having to ask to take something that belongs to me before taking it?

If ten other sites do this, do I have to find them individually and opt out of all of them?

Intent isn’t the issue. If I break into your bank account and take some of your money and give it to doctors fighting the pandemic, my intent may be admirable. It still doesn’t mean I can steal things that don’t belong to me.

It doesn’t belong to you.

Nothing belongs to anyone.