The emotional side of editing (and being edited)

It’s your prose, lovingly crafted. An editor has now started tearing it apart. What’s your reaction? Are you angry? Sad? Hurt? Here’s how to deal with it.

The context for this post is personal. For the last two weeks, I’ve been working on an op-ed about Facebook and similar sites for the Sunday opinion page of a major US daily newspaper. They accepted my pitch and my idea. I interviewed a dozen experts and spent extensive time on web research. Then I wrote something that I thought was awesome and turned it in a couple of days early.

I felt great. They were going to love it.

The editor’s response was positive, but he had a bunch of suggestions. The one that upset me was when he asked to cut a 1000-word chunk from the start of the piece. The whole thing was 2300 words long, and not only was he suggesting that I cut it nearly by half, but that I remove the part that had taken the most research, the heart of the case I was making including all the quotes from the people I’d interviewed.

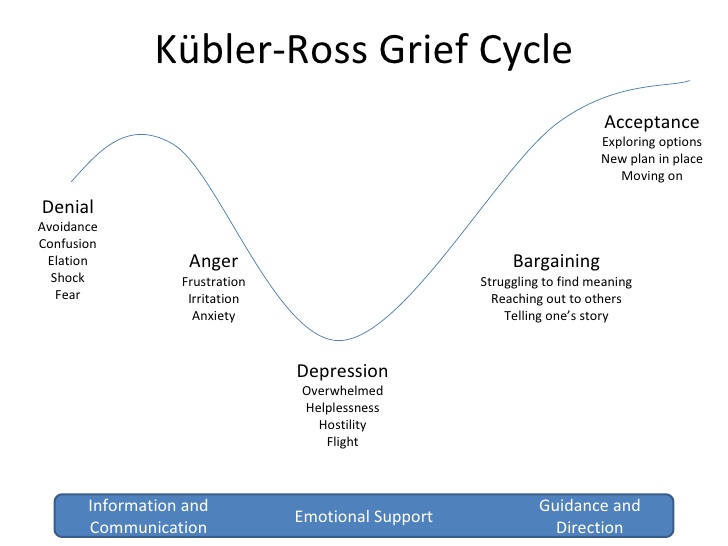

In rapid succession, I flipped through every one of the Kübler-Ross stages:

- Denial. This piece was great. The editor must be mistaken.

- Anger. I’m an awesome writer and somehow they don’t recognize it!

- Bargaining. Maybe I can salvage a piece of this. Maybe they’ll reduce their requested cuts if I explain how essential that part is.

- Depression. I hate this. I pour my heart out into this piece and they crap on it. Why do I bother? Am I cut out for this kind of writing?

- Acceptance. There’s no getting past this without addressing their request, so I guess that’s what I have to do.

I received the feedback in the afternoon. Because I emote rapidly, going through all five stages took about an hour. I decided to work on the piece that evening, because I knew it would keep me from sleeping if I didn’t.

Problem-solving is the key to editing

In the end, it’s simple.

“They hate me,” “They hate this,” “I suck,” “Poor me” — these emotional responses are not helpful to writing. They do not get you any closer to solving the problems the editor has pointed out. They are content-free.

They are unavoidable, but you need to acknowledge the feelings and then get past them.

How?

By concentrating on the work.

The key to great writing is to put your heart, soul, and ego into it while you’re working on it . . . and then treat the words as just words while you are editing. You loved writing it, but now you are you and the text is just the text. Making it better is the job. Put sentimentality aside. (As Stephen King and other great writers have said, you need to be prepared to kill your darlings — the bits of prose about which you feel sentimental — if they’re getting in the way of the story.) This is a hard lesson to learn, but once you’ve learned it, your writing and revision will become not only better, but far less painful.

The reader has no interest in your emotional state. They’re only interested in reading what you wrote. They don’t care if you shed a tear or rail against the editor, but they will care whether the writing is the best it can be.

All writing is solving problems. When responding to edits, you have a particular problem to solve: how can I fix what the editor says is confusing, wrong, poorly organized, or redundant?

When the editor suggests cutting a chunk of prose, you’re probably better off without it. So ask yourself: is this redundant? Do I need this? If I deleted this, what would be missing — exposition, justification, authority? How could I restore those in a few sentences?

Then get to work on fixing it. Since you know so well what’s in the deleted portion, you have all the knowledge necessary to replace it with something pithier.

Once you start working on the problem, the emotional issues should recede. There is no better salve for the pain of editing than the process of creating something even better than what you started with. It’s still your prose.

What this means for editors

The pro-forma advice for editors is to deliver what’s known as the “criticism sandwich” (or, for writers in a bad mood, the “shit sandwich”) — first tell them what’s good, then tell them what to fix, and finish by describing how good it’s going to be.

I always found this a little glib. Nobody is fooled by it. They zoom right in on the problems.

But I had forgotten what it’s like to be on the other end of this, because my writing is good enough that most editors have accepted it without big changes. Now I’m vividly remembering what it feels like.

It is important to start with the positives, because without those, the piece is not worth writing and editing. What is good about this piece? Why is it worth the extra work? Writers need to hear that for motivation.

As for criticism, it hurts, because we are human and the editor is criticizing our creative output. But there are ways to get past that. Editors must:

- Alway critique the writing, never the writer. This helps people get into a problem-solving frame of mind — how can we fix this piece? — and avoid the unproductive “I suck/you suck/everything is terrible” vortex.

- Explain why changes are needed. This flips people into an analytical mode, rather than an emotional one. It gets everyone thinking about solving problems.

- Suggest solutions. If I have a significant edit to make, I always suggest a solution to the problem — how to rearrange things, how to state things differently, or what alternate words you could use, for example. The writer is free to ignore my advice and substitute their own solution, but at least I’ve given them something to start with.

- Use humor. Some errors are just funny, and most writers can laugh at themselves when, for example, you point out that story they just told is fascinating but undermines the main point of their whole piece, or suggest they slap themselves every time they write another passive sentence. A wry smile is the first step to getting past the pain and getting to work on solving the problem.

- Say some positive things, too. Everyone hates reading a constant stream of criticism. It’s a lot easier if there are also comments like “I love this turn of phrase” or “People are going to highlight this passage, it’s so well stated.” It’s the editor’s job to find fault. We need to learn to find positives as well.

- Overall, be encouraging. I never work on useless projects. And I truly care about my authors and their work — most of them are lovely people doing terrific things for their readers. That means I can always, sincerely, say “This is going to be great” or “I love this part” or “This is an awesome idea.” A little heartfelt cheerleading goes a long way.

Editing is, at the same time, a mostly objective analysis of how to make writing better, and an emotional relationship. Focus on the analysis to make prose great. Focus on the emotions to enable writers to embrace their power to create and transcend their imperfections.

P.S. I’m now on draft 7 of the op-ed . . .

I can relate to this – I recently had a piece accepted by a national magazine, but they wanted its length cut by about half. Since I pride myself on writing short, concise pieces, this was a hard pill to swallow at first! I don’t feel like such a bad person for my reaction when you explain it in the stages of grief.

I used to occasionally judge writing contests that promised feedback on the top entries. I told people to whom I gave a lot of detailed suggestions for improvement that all those comments meant they had an essentially good story that just needed tweaks. It’s harder to comment on something that just doesn’t work at all.

You’re lucky to work with professional editors. In the corporate world, where I write, editors are seldom up to the task. My experience can be summed up by this passage from William Zinsser’s On Writing Well:

“A bad editor has a compulsion to tinker, proving with busywork that he hasn’t forgotten the minutiae of grammar and usage. He is a literal fellow, catching cracks in the road but not enjoying the scenery. Very often it simply doesn’t occur to him that a writer is writing by ear, trying to achieve a particular sound or cadence, or playing with words just for the pleasures of wordplay. One of the bleakest moments for writers is the one when they realize that their editor has missed the point of what they are trying to do.”

I’m afraid I had to look up the Americanism “op-ed”! But once I got past that, this was a very sound article. I worked as a technical author and editor, and before that, as a software developer and tester. What all roles had in common is that I was part of a team, trying to produce a good product for a customer who couldn’t care less about any of our egos. As a younger man, this took me some time to grasp, though…

Good post. I feel like I cycle through these stages each time I am edited, and it isn’t easy in the moment. After it is all finished, I have to say that I have learned more about writing by being edited than from anything else. That is particularly true when I find different editors editing the same things in my writing. Reminds me of the saying “If one person tells you you are an ass you can ignore them. If two people tell you you are an ass, go buy yourself a saddle.”

Wisdom.

This is a funny one to me, Josh. I’d been a full-time journalist for a decade and never faced such detailed editing until I was writing an op-ed last year for a national outlet. Via, email there were 17, yes seventeen, back-and-forth exchanges between me and 2-3 editors over the course of 3-4 days to publish a roughly 800-word piece on a cable news outlet’s opinion web section. I’ve never been one to be wedded to a draft so kept rolling with it, but the level of scrutiny was memorable given my old days as reporter banging out scripts and articles on deadline with far less editorial review.