The best parts of me are like my Dad

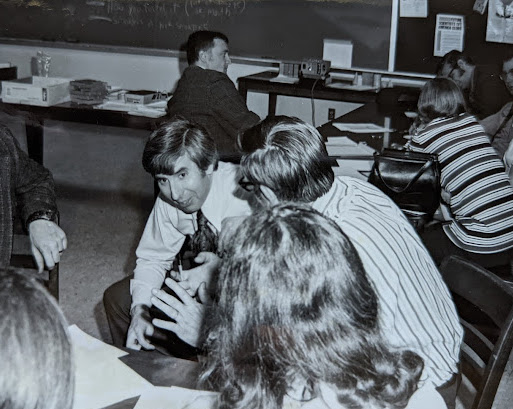

Picture this. It is the 1960s. You are a student at the Ogontz Campus of Penn State University, near Philadelphia, where the students and professors who are unable or unwilling to get into the main University Park campus end up. You are majoring in something other than science, but you need a science class to check off a requirement. You pick Introduction to Chemistry, in the hopes that it doesn’t require too much math, and because you’ve heard the professor is “interesting.”

Today’s class is on ionic bonds. Professor Bernoff enters the classroom with safety goggles, clad head to toe in protective clothing. At the front of the room is a large metal pressure vessel. While describing the chemical principles, he carefully uses tongs to place a lump of sodium, a volatile metal, into the pressure vessel. You are in the first few rows; he asks you to move back for safety, and requests that you let him know immediately if you get a whiff of the next poisonous reactant so he can evacuate the room. Then he connects a large gas cylinder labelled “CHLORINE” to the pressure vessel and twists the valve at the top.

Now he is asking the class what the result will be. A bright kid sitting next to you yells out: “Sodium chloride!” Professor Bernoff responds “Correct!” And with a flourish, he reaches in to the pressure pressure and pulls out . . . a familiar blue cylindrical carton labelled “Morton’s Salt.” Murmurs and nervous laughter fill the room. Obviously the experiment has been staged. But it’s safe to say you’ll never forget today’s lesson: that in chemistry, the end result often has little resemblance to the components that make it up.

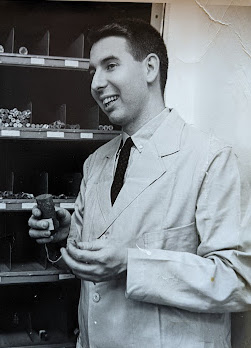

Now you know a little about my Dad, Robert Bernoff, Ph.D. He was passionate about teaching. He loved science and took a logical, scientific approach to most things, often with some kind of a creative twist. He liked to get in front of an audience eager to learn. And when it came to doing the right thing, he often looked for a way to get things done that wasn’t in line with the official rules.

My father died last week at the age of 89. You can read the official obituary in the Sunday Philadelphia Inquirer. But I’d like you to know a little bit more about who he was and what he meant to me.

Getting ahead on brains and grit

My father Robert Bernoff was the child of working-class Russian Jews who came to the U.S. in the early 1900s. He was bright, athletic, and popular — he was the president of his class at West Philadelphia High. Everyone agreed he would go to college, but how to pay for it? After taking a series of odd jobs, he turned a local connection from a friend into an athletic scholarship in competitive swimming. The scholarship paid for his bachelor’s degree, and he went on to earn a Ph.D. in chemistry. He spent a few years as a research chemist and even helped file for patents and start a company. But pretty soon after, he joined Penn State Ogontz as a professor.

If you know anything about academia, you know that the way to get ahead is through research publications. This is why nobody wants to teach the introductory chemistry class — it’s a lot of work, and teaching doesn’t get you tenure.

But that didn’t matter to my dad. He loved teaching. So he volunteered to teach the introductory class and made it fun for the students, connecting what they were learning to topics in the news like pollution and global warming.

He loved teaching us, too

I was born in 1958 and my brother Andy came along in 1960, followed by my sister Marjorie seven years later.

My dad was not one of those sit-in-the-den-with-a-pipe-and-a-newspaper kind of dads. He wanted to be involved in teaching us everything, from a young age.

He got a book on teaching kids to read and applied the phonics principles in it to teach us — and I was reading a year before I entered kindergarten.

My dad also invented a game for my brother and me, called “blockinoes.” He took a bunch of wooden blocks and taped some of them together to make blocks that were multiples of a unit square. To start, you’d dump out a set of dominos and turn them face down. Then, to take your turn, you’d draw a domino, and add up the numbers of dots on it, then select a block or blocks that length and add it to a long column you were building along the floor. The player with the longest column when the blocks ran out was the winner.

Playing blockinoes was fun for a little kid, building those long snaky columns of blocks. But it demanded that you do mental addition and subtraction. My brother and I got pretty good at it. I grew to love numbers, and would delight in doing problems with a pencil for fun, like doubling numbers until I ran out of paper. All this must have given us a good start in math, since Andy and I both went on to win math competitions, major in math, and enter mathematics Ph.D. programs — me at MIT, and him on a Marshall Scholarship at Cambridge in the UK. Andy is now a math professor, while I turned my math skills into a stint at a mathematical software company and a career as a technology analyst.

Everything we did as children became an exploration. How does the toilet work? What does a leaf look like under a microscope? How does a magnifying glass heat things up when you use it to focus sunlight? Every week we would go to the library and take out new books — and my favorites were books on astronomy, science, and geography. Unlike today’s high-pressure parents, my parents didn’t drive us to work hard and excel. Instead, my father ignited our joy in figuring things out and we took it from there.

Every home project was a learning opportunity as well. I vividly remember an afternoon on which my father was mounting some track lighting on a beam on the ceiling in our dining room and attaching it to a switch on the wall. In true do-it-yourself fashion, he just ran a wire inside the wall from the lights to the switch. It didn’t work, but there was a clue: when we plugged an electric drill into a nearby outlet, you could make the lights go on by running the drill. In fact, the faster you ran the drill, the brighter the lights would shine. My brother and I started making circuit diagrams on scrap paper to hypothesize what wires inside the wall would result in this behavior. We not only figured out what the circuit must look like, but that you could relocate wires around the outlet to cause the switch to operate the lights properly. And sure enough, it worked. It may have seemed like amateur electrical work, but we were learning how to solve problems with logical thinking.

My dad made an impact on millions of students

When we were in elementary school, my father learned just how little time teachers in the 1960s were spending on science. He attended a lecture from a prominent science educator and pitched himself to the lecturer as a potential team member on a team creating new science curricula.

This was the beginning of an interesting twist in my father’s career. While his colleagues were doing research in chemistry, he was helping create new science teaching materials for use in schools. He spent one summer in Michigan helping to develop a new elementary science program called “Science: A Process Approach.” He even got my mother a job on the team: she was an artist who did illustrations for the text.

My dad met and then teamed up with two women to create a company dedicated to science education: Mary Budd Rowe, who eventually became head of the National Science Teacher’s Association, and Emily Girault. Together, they pitched and won grants from the National Science Foundation to build new science materials for use at all levels in schools. He also ran workshops for teachers, focusing on best techniques for inspiring students. His materials and the teachers he taught were part of science learning for millions of school students in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.

This led my dad in unusual directions for a chemistry professor. As part of his grants, he tested out the teaching materials by teaching at the elementary, junior high, and high school level at our local school district. He also wangled a summer appointment teaching teachers at the US armed services schools in Europe, which turned into a repeating set of European assignments. He even brought us all along on one of these trips. As a result, I got to travel all around Europe with my family as a teenager.

My dad felt it was a great idea to introduce his kids to other cultures and other kinds of people. This made me interested, too. Luckily, my wife has the same attitude, and we’ve traveled all over Europe and North America with great enjoyment.

My father’s choices made things difficult for his university career. He had plenty of publications. He was generating grant money. And he was teaching the intro to chem class that nobody else wanted to teach. But it was an uncomfortable fit for a chemistry professor. His department head told him to stop with the science ed and concentrate on chemistry — but he didn’t listen. When the time came to put him up for promotion to full professor, this created a conundrum: he was clearly not a full professor of chemistry in any traditional sense.

As a result, the administration promoted him with a new title: “Professor of Science and General Chemistry.” (“General Chemistry” is a code word for low-level chemistry that no chem professor would ever be proud of.) That title is still unique in the history of Penn State.

Joining the campus leadership — on his own terms

My dad was quite comfortable just teaching and creating science materials. But in the late 1970s, the Penn State administration asked him to serve on the search committee to find a new dean and campus executive to lead the Ogontz Campus.

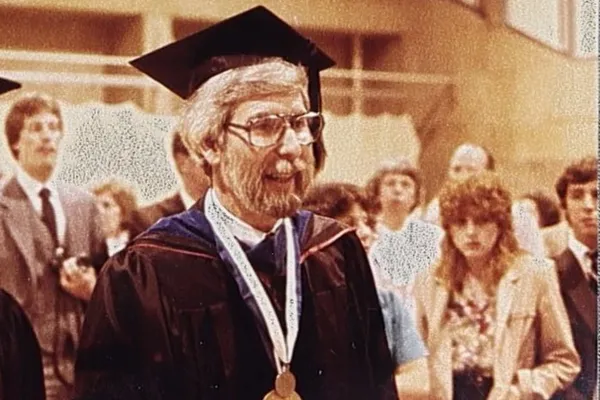

After a year, they hadn’t found an acceptable candidate, so Penn State asked him to serve as acting campus executive officer. A year after that, they made it permanent. My father was the CEO of the Ogontz campus of Penn State from 1979 to 1990.

I was a Penn State student at University Park, graduating in 1979. I arranged to graduate at Ogontz, though, so my dad could hand me my diploma.

Because being an administrator was not really his ambition, he did things his own way. He hired and promoted professors based on teaching, rather than an exclusive focus on research. Ogontz became the campus with more more full professors than any other, aside from the main campus of Penn State in University Park. It attracted a diverse student body. And Ogontz professors won a disproportionate number of teaching awards.

The leaders of the other Penn State campuses would point out how he often synthesized differing points of view into a solution that would work for everyone. I think this was because he was more focused on solving problems than on the politics of getting ahead in the university.

At one point, a student in history completed the requirements for a bachelor’s degree while going to Ogontz. This was against policy — students were supposed to go to Ogontz for two years, then move on to University Park to complete their degrees. My dad insisted on giving that student the degree he had earned, infuriating the university president. But soon after, partly based on that precedent, the commonwealth campuses started becoming more independent. Now many of them grant four-year degrees, the Ogontz Campus is known as the Abington College of Penn State, and my father’s successors are known as chancellors, not just deans.

In the 1990s, my dad returned to the faculty for a few years, then retired. But he never stopped teaching. He taught himself to use computers and presentation software after he retired, then became adept at using them to present talks. Even in his 70s and 80s, he was teaching seniors on topics like fracking, artificial intelligence, and gene editing. The man just never stopped learning and teaching.

Even towards the end of his life, as he was dying of melanoma, he remained curious. When the time came to hook him up to oxygen, the hospice people sent us a machine called an oxygen concentrator. My dad became curious about its operation, googled it, and then explained to all of us the clever chemistry that the concentrator used to separate the oxygen in the air from the nitrogen and use it to help keep him alive.

What I learned from my father

My father taught me a lot of things: how to catch a baseball, how to drill a hole, how to drive a stick-shift. But of course, the most important things he taught me were taught by example. Everything good and admirable about me came from trying to be like my father.

The most essential of those things was a focus on logical problem-solving. This is the attitude of a scientist. When you want to change things — whether that means mounting a switch plate or changing the way people think — you approach it systematically. You gather data, form hypotheses, test them, and use logic to figure out what’s actually happening and how to change it. That may have started with the track lighting in the dining room, but it became central to how I approach everything in my life.

My career was informed by my dad as well. I’ve had plenty of setbacks, from leaving graduate school to getting laid off from jobs. But I took each of those as an opportunity to reset and move in a new direction that was better for me, much as my father did when he moved from chemistry researcher to college professor to science curriculum developer to dean.

But perhaps the most important thing I learned from my dad was how to love.

He and my mom loved me unconditionally. Their marriage was one of mutual trust and support. Those were powerful things to be a part of. It took a long time and at times I despaired, but I found a woman I could love the way my parents loved each other, and who would love me the same way. (She told me that when she saw how my father treated my mother, she decided I was probably acceptable husband material.) We’ve been married for 32 years.

And I have tried to love my children the way my parents loved me — with encouragement and warmth, but without judgment. I’m happy with how they have turned out so far, and with the people they have chosen to share their love with as well.

My dad’s life was long and rich and full of positive effects on the people closest to him, as well as on thousands of people he taught and millions who learned from the materials he created. His life was a wonderful thing to be a part of. The best parts of me are the ones I got from my father.

Lovely remembrance.

What an amazing life.

What a beautiful, thoughtful tribute to your Dad, Josh. He clearly was an extraordinarily talented man of many great gifts, one of the best being you. You certainly gave him a great, great deal to be proud of. My condolences to you and your family at this sad time. May your father’s memory be a blessing.

Josh, that was a beautiful tribute. Thank you for sharing it.

Bravo!

I am so sorry for your loss. An amazing tribute to your father. May his memory be eternal.

Thanks for sharing. Got me to pause a moment and remember my dad

Tears in my eyes, lump in my throat. Wonderful dad, wonderful tribute, wonderful legacy.

Sorry for your loss, Josh. Wonderful tributes to a neat guy and great dad.

This is an amazing summary of the life of an amazing man. I will keep you and your family in my thoughts. May his memory be a Blessing.

It seems Robert Bernoff left this earthly life a wealthy man. Despite his success as a passionate educator, I wager he would cite you and your siblings as his greatest achievement. You didn’t say whether he inspired you to write; you have married his critical thinking skills with the creativity afforded you by the pen. Well done, friend. Godspeed, Robert.

He inspired me to write and make a mark on the world.

I am sorry for your loss. My condolences to your family. Thank you for sharing this remembrance of your father. May your memories of the time that you had together continue to be a measure of solace and a blessing.

This is a beautiful tribute, Josh. Your dad sounds like an exceptional man who lived a meaningful life, and who was well loved. I am sorry for your loss. I’m also glad to know the part of him that lives on in you. <3

That’s an awesome tribute to your Dad Josh. I too was born in 1958. My Dad is still alive, he will be 88 this summer.

I love great examples of a life richly lived and filled with happiness. Thank you for sharing your father’s and now your life as well. I empathize with you but I also know at our age what it means to possess all the great memories to cherish the rest of our lives. Hey, I love your book. It’s a great reference for me.

Beautiful tribute to a lifelong learner and inspiring Dad! So sorry for your loss. Thanks for sharing, Josh.