The Tax Policy Center demonstrates how to screw up and recover

The Tax Policy Center, a nonpartisan organization that analyzes tax proposals, posted and then retracted an erroneous analysis of the Republican tax plan. The problem took several days to fix. If you ever screw up (and who doesn’t), take notes; this is a great case study in how to recover.

What does a tax proposal actually mean, without the spin? The Tax Policy Center, a Washington nonprofit, exists to answer that question. The TPC has a model that, based on a huge database of aggregated past tax filings, has a detailed picture of all the tax filers in the nation. So when somebody proposes a tax change, the TPC crunches the numbers and answers questions like how much more will people save or pay and who will benefit most.

TPC’s economists, including its former director whom I’ve profiled in a previous post, have diverse perspectives from across the political spectrum. This is crucial, because the organization maintains a consistent reputation for unbiased analysis. Both liberal and conservative politicians had until recently respected this reputation, but followers of Donald Trump and, more recently, the editorial page of the Wall Street Journal, have accused the organization of bias.

This was the backdrop when on November 6 — Monday — the TPC scored the Republican tax cut proposal, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The demand for these analyses is fierce, because reporters and readers want to know, with great urgency, the answer to questions like “What percentage of the tax savings go to the top 1% of taxpayers?” Soon after the TPC released its analysis, it took it down again. Its economists had discovered a serious error in the calculation of the Child Tax Credit, which significantly affects the size of the tax breaks going to lower-income families. Now the pressure on the organization was even more intense, because until it fixed the problem, all that was out there were outdated, erroneous copies of the report and stories about the retraction.

How to recover from an error

What happened next is a case study in error recovery for a research organization.

First, TPC took the time necessary to fix and then carefully verify its analysis before releasing the revised version yesterday. One error would not destroy this organization’s reputation, but a series of errors certainly could. Getting it right the second time isn’t as good as getting it right the first, but it’s a lot better than screwing up again.

The abstract for the revised analysis includes an uninflected note about the revision:

ABSTRACT

NOTE: This is a corrected version of the analysis originally published November 6, 2017.

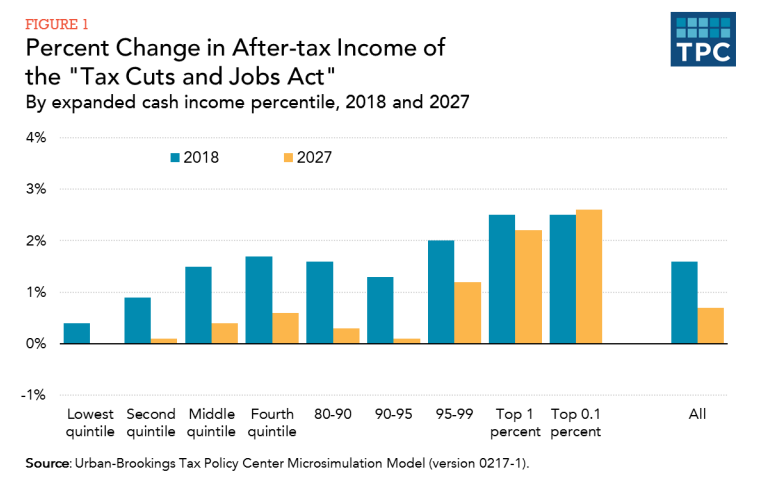

The Tax Policy Center has produced preliminary distributional estimates of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act as introduced on November 3, 2017. We find the legislation would reduce taxes on average for all income groups in 2018 and 2027. The largest cuts, in dollars and as a percentage of after-tax income, would accrue to higher-income households. However, not all taxpayers would receive a tax cut under this proposal—at least 7 percent of taxpayers would pay higher taxes under the proposal in 2018 and at least 25 percent of taxpayers would pay more in 2027.

Then, separately, the organization’s director Mark J. Mazur published a blog post that explained the error. It’s only 287 words long:

Retracting And Correcting Estimates

TPC staff found an error in the preliminary distributional tables and analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) that we released on November 6, 2017. We pulled back the analysis as soon as we found the error. Our corrected analysis is available here.

The error involved the refundable portion of the child and family tax credit in the proposed legislation. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would replace the existing $1,000 child tax credit with a child and family tax credit equal to $1,600 per qualifying child under age 17 and $300 per taxpayer and nonqualifying child dependent. Similar to present law, the new credit is partially refundable up to $1,000 per qualifying child.

The error caused us to understate the average tax cuts for low- and middle-income taxpayers—particularly in 2018—and overstate the fraction of taxpayers who would face a tax increase. In addition, it caused us to overstate the average tax cuts for certain upper-income taxpayers subject to the phaseout of the credit. The error had an especially large effect on the more detailed TPC distributional tables (e.g., by filing status, by presence of children). Corrected versions of the detailed tables are available here.

TPC is committed to providing the highest-quality information about America’s tax system. However, we know we fell short this time. We appreciate the support that all of you have provided to TPC over the years and we will work hard to meet our high standards going forward.

Note: This blog was updated on November 8, 2017 to reflect TPC’s corrected analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. To see the changes between our original estimates and our corrected estimates, click here.

This is perfect. It briefly does everything it needs to do, in the right order:

- It clearly describes what happened and links to the new report

- It describes the error.

- It describes the consequences of the error, which is important since reporters had already published some articles about the erroneous report.

- In one sentence, it describes the organization’s continuing commitment to quality, rather than indulging in an extended spectacle of self-flagellation.

- Finally, it links to a table that shows the differences between the old estimates and the new ones. The new table shows that the original estimates significantly underestimated savings for the second and third quintiles of taxpayers, which would have fueled more ire from liberals. Rather than attempting to conceal these differences, which could have led to further accusations of liberal bias, the TPC puts them on the Web where everyone can review them. But it keeps the emphasis on the accurate estimates, which are the important story here, rather than on the mistake.

I have only one quibble with this strategy. TPC has erased its original November 6 blog post about the error and retraction, replacing it with the new post about the revised estimates. To retain a reputation for honesty, bloggers should never take down a historical post. If you have a correction to make, add a note to the original post and link it to a new post about the revision.

But overall, the TPC’s communication strategy was excellent. It moved smartly and deliberately, didn’t hide its mistakes, and maintained its reputation for honesty and fair dealing.

So, what about the tax plan?

In case you’re interested, here’s what the analysis shows about who makes and saves money in the Republican Tax Plan.