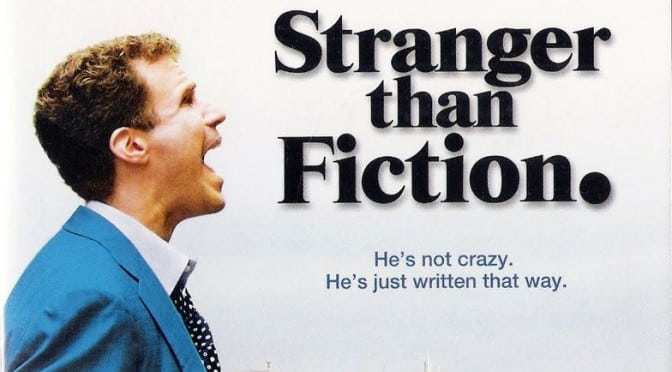

Stranger than fiction

Nonfiction writers need to tell the truth in a captivating way. Fiction writers just need to be captivating.

At first glance, it seems like there are more constraints on nonfiction. After all, fiction writers can just “make stuff up,” while nonfiction writers are constrained by what actually happened.

There are actually more constraints on fiction

As I talk to writers, though, I’ve noticed that fiction has a lot of constraints on it.

The most important is that fictional accounts are stories. Nonfiction describes the world, and the world is under no obligation to behave according to a neat story. So nonfiction writers need to cast around until they find “the story” in the reality they are describing — and they can’t fudge the facts to make the narrative more entertaining.

Fiction has characters, and characters have motivations. Nonfiction describes people whose motivations may be completely at odds with their actions. People can and do behave in irrational, inexplicable ways. That would never fly in fiction.

There is a limit to how many characters appears in a fictional account (George R.R. Martin not withstanding). The number of potential actors in a reality-based account is virtually unlimited. There are always people influencing the action whose contributions are so minor that it’s not worth describing them in detail. There’s no “edge” to a nonfiction account of what happened — any boundary that you draw to decide who and what to include is artificial.

Fiction makes sense. Reality often doesn’t.

Fictional stories have endings. Reality goes on forever.

In fiction, the good guys usually win. In reality, sometimes the bad guys win, and often, it’s really hard to tell if anybody actually won, or who the good guys and bad guys are.

Fiction rarely includes data. Nonfiction often does. In fact, there is usually a vast collection of data to choose from. Selecting what data to include is its own challenge.

Are you getting the picture?

In a fictional account, there is no path and no landscape at first, and you get to describe the landscape and the path through it.

In nonfiction, the landscape extends infinitely in all directions, there are infinitely many possible paths, and any path you choose could end up virtually anywhere at all.

Which is harder?

I can’t really speak intelligently to this, as writer of (mostly) nonfiction.

But I admit to some jealousy of fiction writers who get to define not just the stories they tell, but the morals of those stories.

I have to find a story worth telling in the trackless void of reality — and I’m not allowed to just make stuff up.

It’s a fun challenge. But to fiction writers looking at it and thinking “Well, you have everything already defined for you,” I say, you have no idea.

It’s pretty intimidating. If you really like stories with rational characters and believable plots, stick to fiction. You’re safer, trust me.