Should you trademark a hashtag?

Hashtags are great, but you don’t control them — anyone can post on them. So why not apply trademark protection? Because control and enthusiasm are inverses — the more you seek one, the less of the other you get.

At one of its recent events, the Massachusetts Biotech Council was tweeting with its trademarked hashtag #PATIENTDRIVEN®. Here’s an example:

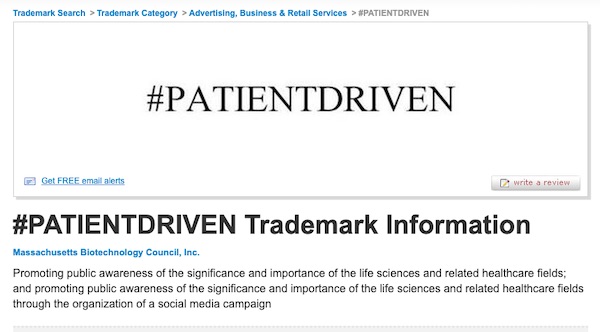

I, along with some of my Facebook friends, had never seen a trademarked hashtag before. The first thing I did was to check Trademarkia, and sure enough, MassBio has registered this trademark including the hashtag symbol:

The purpose of a trademark is to protect an organization’s logo, word, or phrase from unauthorized use by other people. That’s why I can’t start marketing a line of shoes called “Nike” that I make myself — Nike will sue me and shut me down. Trademarks apply in limited domains (I’m free to create a Nike Accounting Service, for example). In this case MassBio is attempting to protect the mark, hashtag included, from use by others in health care.

It’s failing at that. Here’s a Twitter post by a commercial company that uses it.

That’s actionable, according to trademark law. They could send a cease-and-desist.

In order to protect the trademark, the organization has to not only include the ® symbol, but also warn off others with text like “#PATIENTDRIVEN is a registered trademark of the Massachusetts Biotechnology Council.” As far as I can tell, there is no warning of that kind for #PATIENTDRIVEN anywhere on the internet. A lawyer would tell you that if you can’t put it the warning in the tweet, you should at least put it in your Twitter short bio. MassBio’s short bio reads “MassBio is committed to advancing MA’s leadership in the life sciences to grow the industry, add value to the healthcare system & improve patient lives.” Very nice, but no trademark warning. And it’s not on their homepage at massbio.org, either.

Why trademarking a hashtag is bonkers

The purpose of a hashtag is to encourage people to spread an idea. If they spread it, more people hear about it. The flip side of that is, if they spread it, you lose control of it. If I want to put #NoOneCanHearYouScream on my tweets about the impeachment proceedings, the folks who made the movie “Alien” don’t get to complain.

As the social media expert Cari Bugbee posted, “The whole point of a trademark is to prevent other people from using your name or phrase, which is the opposite point of a hashtag.”

Consider for a moment the situation of someone who attempts to spread and share tweets from MassBio’s event. First off, you don’t want them searching for the button that inserts the ® symbol into the hashtag, that will slow them down. And secondly, you don’t want them worrying about whether you will sue them for using their hashtag. Here’s a tweet from that conference. Is Christopher O’Toole taking a legal risk by posting this?

MassBio could argue that of course they won’t sue tweeters unless somebody abuses the hashtag. But how is the audience supposed to know this? Do we need a disclaimer for the hashtag? And if we had one, would the organization’s trademark lawyers say it’s weakening the trademark?

It’s scary putting a hashtag out into the wild. When people are scared, they hire lawyers to protect them. But don’t get confused: trademarking a hashtag is a bad idea. If you want an idea to spread, you’ve got to set it free — and at that point, people will do whatever they want with it.

This scenario reminds me of a time a few years back when I worked for a large tech company. Its execs would debate the rules for using hashtags for their tweetchats. They tried to control them as opposed to let them organically develop. They clearly didn’t understand hashtags and, more generally, social media.

An intellectual property lawyer gave me a general guideline approximately a decade ago: if you as an individual are the owner of a trademark or registered phrase, you need to affix the ™ or (r) symbol to each instance that you use the protected item in a visual form, in order to maintain your protection. Other people are generally not required to do that, as long as they are not attempting to monetize that protected item.

The example that lawyer shared with me: the manufacturer of Kleenex and their employees would need to use the symbol when mentioning the product while conducting the business of the company, but a member of the public discussing that brand of facial tissue does not.

Expanding into the realm of hashtags, my opinion is the holder of the intellectual property might be obligated to add the extra symbol, whereas the layperson would not be. And I don’t know if the hashtag trending statistics would be able to track the annotated version along with the plain version.

I am not a lawyer. I would be interested in seeing feedback from intellectual property lawyers regarding this subject.

If you’re a small fish in a huge pond, trademarking your hashtag makes no sense unless you want to be the next FIFA (s).

The Olympics (IOC) and the NFL are two larger businesses that have trademarked hashtags. The goal of trademarking a hashtag is to maintain some kind of control over the online conversations about your brand. You don’t need to prevent anyone from using your hashtags if you have the correct tools and social support; you can monitor the conversations yourself and participate in them in real-time!

According to what we’ve seen, rather than forbidding you from using their hashtag, several major businesses actually urge you (ask you!) to do so.

Whether a large business supports or discourages the usage of its branded hashtag is likely to be determined by their entire social media strategy and online customer care approach, as well as their customer relations social media, and marketing budget.