Shakespeare didn’t plagiarize. He drew inspiration . . . just as you should.

A New York Times article with an inflammatory title suggests that, according to new scholarly research, Shakespeare’s plays drew heavily on a manuscript by another author. For Shakespeare scholars, this is a revelation. For the rest of us, it’s a good demonstration of the difference between plagiarism and inspiration.

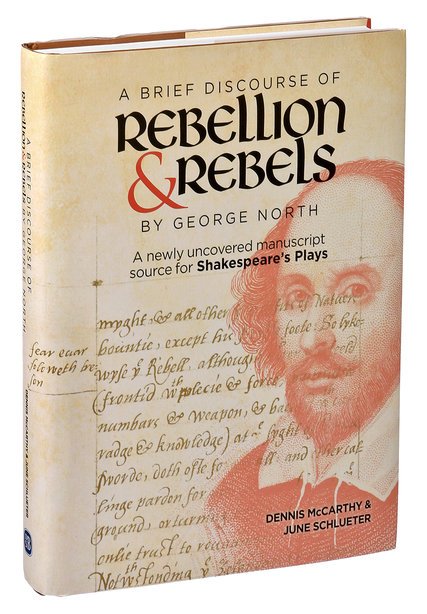

The title of the Times article is “Plagiarism Software Unveils a New Source for 11 of Shakespeare’s Plays.” This is clickbait. As it says right in the article:

The authors [of a new book] are not suggesting that Shakespeare plagiarized but rather that he read and was inspired by a manuscript titled “A Brief Discourse of Rebellion and Rebels,” written in the late 1500s by George North. . .

The scholars in question, Dennis McCarthy and June Schlueter, describe how, by using the same software that professors use to test papers for plagiarism, they determined that Shakespeare’s works incorporated many words and ideas from the North manuscript. For example, North uses several specific words in his argument that ugly people should strive for inner beauty, and Shakespeare uses some of the same words and concepts in Richard III. And Shakespeare, in various plays, uses the same set of words as a synonym for “dog” that North does, notably, “trundle-tail.”

If you are in the small, intense group of people researching where Shakespeare’s ideas came from, I’m sure this research is a big deal for you. But what about the rest of us?

Plagiarism, borrowing, inspiration, and other forms of intellectual intercourse

Plagiarism, in its purest form, is stealing the words of another without a clear citation indicating the source. It is always wrong. As a writing, I hold plagiarists is the lowest possible regard, because they appropriate what is closest to my soul: my writing.

Plagiarism of ideas is also wrong, if not as easy to prosecute. If I have an idea and that idea is original, and you claim to have come up with the same idea, I’m going to have a problem with that. But ideas float around in the air like whiffs of flowers on the breeze. Sometimes the moment is right for two or more people to have the same idea, independently. (Isaac Newton and Gottfreid Leibniz independently invented calculus and then spent decades resenting each other for stealing the idea.) If you not only describe the same idea, but with the same arguments for it, the result is suspicious.

These days, it’s far easier to do your homework regarding ideas. When you come up with an idea, Google it; if somebody else has published it, even if you came up with it on your own, cite her work in what you write. It’s not that hard.

Much more commonplace than stealing words or ideas, however, is inspiration. What are your favorite words, the ones you come back to? Like Shakespeare, you probably got them from reading somebody else’s work. In my books, I like to write paragraphs suggesting something, followed by a short sentence like “That’s baloney.” I’m not sure where I got that (Seth Godin, perhaps), but I’m sure I copied it from someone. Stylistically, that’s not stealing, that’s inspiration.

Each of us has developed a writing style that is a pastiche of concepts and words from others and a few original ideas, recombined in unique ways. Shakespeare did it, and so do you.That’s not plagiarism. That’s writing. And it’s just fine.

Why most writing sucks

Thinking on this, I recognize why so much writing is bullshit. If most of what you read is overwritten, poorly organized, passive voice, jargon-filled bloviation, then you come to think of that as a normal way to write. You learn to write the same way and carry on the cycle.

Please stop. Learn to be better. Read non-fiction prose stylists like Godin and Malcolm Gladwell and Mary Roach and Matt Taibbi. Read James Gleick. Read well-edited journalism like The New Yorker and The Atlantic. And understand what they’re doing right. (There is a book about this stuff, you know.)

Shakespeare’s writing was better than what he read, even if he drew his inspiration from those sources. You may not be Shakespeare, but you can do that just as he did.

When I encounter small mistakes in writing, they grate. Today it’s just misspelling James Gleick’s last name. (I before E except after L?) My impression is that the frequency of such small mistakes in your blog seems to be creeping up. I’m a fan of your blog, so say it ain’t so, Joe.

I bet a column or two on how to proofread and how we can make our writing better via proofreading would be valuable. I’d welcome that.

Entirely fair point, Keith. I was in more of a rush than usual this morning.

I actually did a piece on proofreading. It’s here: https://bernoff.com/blog/13-proofreading-hacks-based-psychology-reading

To write something worth others reading, you need to be curious, to explore ideas, to shine a light in dark corners, and be able to alter your own views on the basis of new information.

To then incorporate these altered thinking and ideas into your own world view, to build and expand them, alter the context, and make them more accessible and useful is what it is all about.

This is not plagiarising, it is paying homage.

I like this idea/quote of yours: “Shakespeare’s writing was better than what he read, even if he drew his inspiration from those sources, “especially the first phrase.

It is weird that for the most part in the real world, R&D (rip-off and duplication) is expected, more so in some professions than others, but in academia, it is a fatal sin.

I think it is nice, but not sure if necessary, to cite your inspirations as it helps me to understand where you are coming from and where I can learn more.