Science fiction and analytical thinking

I was a science fiction fan growing up in the 60s and 70s. I was a technology analyst, predicting the future, in the 90s and 00s. Here’s what science fiction and strategic analysis have in common — and what they don’t.

How science fiction challenges the mind (and “sci-fi” doesn’t)

Science fiction is not the same as “sci-fi.” The science fiction I read 40 years ago was speculative. It said, “Let’s extend a trend we see now and figure out how the world would look in the future if that trend continued. And let’s tell stories about people living in that world and the challenges they face.”

I’m talking about Robert Heinlein speculating about space travel and people who could live forever, Isaac Asimov on robots living among humans, and Philip K. Dick examining our minds on drugs.

After a bit of a dry spell, this continues today. You have Cory Doctorow writing about the surveillance state and ubiquitous social media, Paolo Bacigalupi on a world where the struggle for water remakes politics, and Neal Stephenson‘s epic exploration of virtual worlds.

A funny thing happened to science fiction: success ruined it. Specifically, science fiction got popular because it got visual — because of movies and special effects.

Star Trek was really the start of this, and the original series featured some stupid, silly plots about mind and body exchanges, but also some serious science fiction explorations of themes like the doomsday machine and the final outcome of racism. Some of the best science fiction writers wrote for that series, including Theodore Sturgeon, Harlan Ellison, Norman Spinrad, and Robert Bloch.

But what passes for “science fiction” in the biggest movies now is more like fantasy — it’s just elves and dwarves and wizards in spacesuits. Star Wars may be “sci-fi”, but it’s not science fiction. It excites our senses but doesn’t teach us anything about how the future might look. (It’s not a coincidence that it’s set “long ago in a galaxy far, far away.”) The Matrix trilogy may look like science fiction, with its virtual worlds and robot intelligence, but it’s really just another war story with a superhero at the center.

Lately, I’ve been excited to see visual science fiction once gain exploring the future and challenging the mind. Arrival poses serious questions about alien thinking and human geopolitics. Westworld was a fascinating exploration of the moral consequences of creating synthetic intelligent beings.

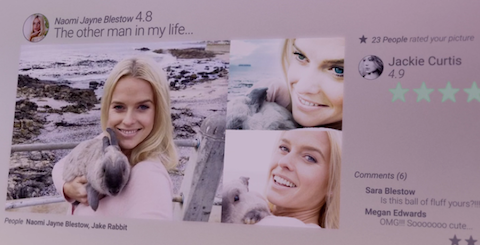

The greatest of these, from the perspective of making you think, is Black Mirror. This British series, available on Netflix, asks serious questions with direct relevance to today. Could we live in a world where everyone rates everyone else on social media — and your rating determines what privileges you receive? What if a device behind our eyes recorded everything we ever experienced — would we spend our lives reliving past experiences? Could we bring back the dead by having AI synthesize them from their on-line posts and videos?

These stories are entertaining because the characters are humans — with all their familiar emotions — dealing with novel situations that are entirely plausible based on today’s technology. The futures of Black Mirror are terrifying exactly because they’re not fantasies. I’ll never live in the world of Star Wars or The Matrix, but I’m worried that I might live the futures of Black Mirror.

Great speculative fiction is like a warm-up for an analyst

A strategic analyst examines current trends and projects the future based on those trends. This is most valuable when the future is unlike the present. For example, in 2008 with Groundswell, Charlene Li and I saw that social media would change how companies interacted with the world — the shape of that future was of intense interest to corporations who had no guidelines on how to succeed within it. It doesn’t matter whether you are analyzing the future of cloud-based software, cybersecurity, 3D printing, or streaming video, the general shape of the analysis is similar:

- Identify a trend that could make a disruptive change in the world.

- Figure out the basic elements of that change.

- Project when and how the change will roll out.

- Identify the consequences of that change, by logically inferring what additional changes could happen.

- Provide strategy advice on how to plan for and profit from the change, based on those consequences.

With enough analytical thinking and help from other thinkers, you can get pretty good at steps 1,2, 4, and 5. Step 3 is a bitch, though. It’s easy to predict the future, but it’s hard to predict exactly when it will get here.

Science fiction basically glides right by Step 3, because unlike the clients of an analyst, science fiction readers and viewers don’t care if you get the timing wrong. The future in Black Mirror seems within reach, but I couldn’t tell you whether it will happen in 2018 or 2028. The people in their worlds don’t wear weird clothes or hairdos or live in plastic houses; they look like us; the difference is in how they deal with the world, not their wardrobes or weapons.

If you are trying to get better at analytical thinking, read and watch serious, speculative science fiction. Write your own speculative vignettes. Stretch your mind, stretch your logic. Ask “What are the logical consequences of what is happening now, and what will happen soon?”

Having trained your mind this way, you can get better at predicting the future of business, of government, of health care or education. You’ll have to rein in your fantasies a bit to make them tame enough to be called “analysis.” But that’s ok, because becoming imaginative is the hard part; taming your imagination enough to speak with businesspeople is a lot easier.

“Let That Be Your Last Battlefield” taught the young me that racism (and by extension, all the other isms) was bullshit. For my money, it was one of the most significant television episodes of all time.

Nice, Josh.

You remind me of my first experience reading Ursula LeGuin (Left Hand of Darkness, in which, among other things, people’s bodies shift based on their relationships, allowing them to gain or lose the ability to bear children). As the daughter of two anthropologists, she speculated not so much on alternative technologies as on alternative social constructs. If Isaac Asimov wrote stories where robots are just as sexist as we are, LeGuin wrote about people where the nature of the sexes – and therefore, the social constructs about sex and sex-roles – has been changed.

I wouldn’t say that LeGuin’s work speculates about the future of technology and its impact. But it certainly speculates on the future of the social constructs that limit us as humans. In that way, her work might overlap with the work you are praising here.

Indeed, science fiction is a sort of super-genre that includes all kinds of speculation. Alternate history can be just as informative and grounded in science as far future stuff. All around us, we see events unfolding that have been predicted by one author or another. We must hope and work for something other than a dystopia.