Renoir at The Clark: How should we feel about all that flesh?

The Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, western Massachusetts, has mounted a comprehensive exhibit of the nudes of impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir. It’s impossible to see these paintings and sculptures in a public setting without some complicated feelings. I’ve never visited an impressionist art exhibit with a content warning before.

I visited The Clark this weekend. (If you’re interested in Renoir, get out there soon; the exhibit ends on Sunday September 22). The curators have done a terrific job of putting Renoir’s lifelong study of the female nude in context with his career, his life, his ambitions, and his influence on other artists including Picasso, who was an avid Renoir collector.

The nudes themselves are incomparable. Make no mistake, this is a study of flesh, light, color, and paint. It’s endlessly fascinating — it clearly fascinated Renoir — and as I perused the gallery with a mostly older mixed gender crowd, I had a curious double vision. As an admirer of impressionism, I was drawn into Renoir’s continued study of light and color and texture, much as you might be while looking at Monet’s many paintings of haystacks.

But as a man in 2019, I certainly had to wonder about these subjects, who, it has to be admitted, are hardly even human beings in these pictures. Their too-small heads, creamy flesh, and vapid expressions make them objects rather than people. Peter Schjeldahl, art critic for the New Yorker, expertly pokes us in the eye for how we see them in his article “Renoir’s Problem Nudes“:

Renoir took such presumptuous, slavering joy in looking at naked women—who in his paintings were always creamy or biscuit white, often with strawberry accents, and ideally blond—that, [art historian Martha] Lucy goes on to argue, the tactility of the later nudes, with brushstrokes like roving fingers, unsettles any kind of gaze, including the male. . . .

There’s no beholding distance from their monotonously compact, rounded breasts and thunderous thighs, smushed into depthless landscapes and interiors, and thus no imaginable approach to intimacy. Their faces nearly always look, not to put too fine a point on it, dumb—bearing out Renoir’s indifference to the women as individuals with inner lives. They aren’t subjects, only occasions. (His models were often amazed at how little they recognized themselves in pictures that they had posed for.)

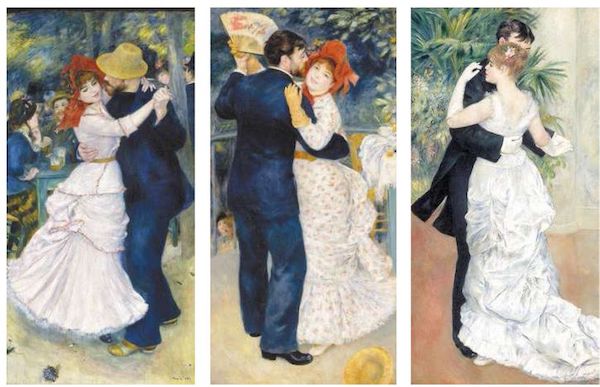

Judging the art of the past by the standards of the present is, of course, always problematic. Things were different then. By any art history standard, Renoir hugely changed the art world. But are these women or haystacks, to be scrutinized, dissected, and displayed in such detail? Renoir is capable of showing emotion in his subjects — his dancers could charm any of us — but emotion and inner life are curiously missing from these nudes.

The content warning

The Clark, of course, is not oblivious to Renoir’s conflicted reputation. So I was fascinated to see this warning on a panel tucked away near the start of the exhibit.

From the Exhibition Team

The aim of Renoir: The Body, The Senses is to present Renoir’s long and extraordinary career through a single subject, one to which he returned through all major phases of his production. Renoir’s artistic treatment of the nude grew from his admiration of the art of the past, but from the 1860s to the end of his life he balanced respect for tradition with radical innovation. In our time, we view the subject matter of these historic works through a contemporary lens — one that brings a heightened focus on issues of class, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. We welcome a range of responses to this exhibition and encourage conversation about the significance of such art today.

I find the little bits of text that curators mount near artworks to be maddening — they tend to alternate between historically fascinating asides and superior art history attitudes revealing things the rest of us can’t see, because we weren’t trained to see as they do. This is certainly of a piece with those placards, because it’s obliquely referencing something that really ought to be out in the open. “We welcome a range of responses” — really? That’s what’s you needed to say?

So, as usual, I’d like to post an honest translation of what this could have said, if only curators spoke like normal people.

Renoir was fascinated with the female nude for his whole artistic life. He transformed the art world with the works you are about to see.

That said, you’re going to be looking at a talented painter’s fascination with women’s flesh. If you look at their faces, you may wonder if these are actually human beings.

These paintings were made, for the most part, in the second half of the Nineteenth Century. The way they portray women is irreducibly part of the era in which they were painted.

So as you look at these works, see beyond the art. See the attitudes. And think carefully about your own.

If we’ve made you think a bit even as your senses are flooded with these images, perhaps that was worth it.

I could do without either content warning. Don’t need to be told how attitudes in the 1860s were different from today’s. In fact, in this kind of exhibition, I don’t want to think about today at all. Also, the models look “dumb”? Doesn’t matter. They may seem like portraits, but they’re not. They’re elaborate painting exercises, studies of flesh and light. Yes, for all intents and purposes, flesh objects. As for thinking about my attitude or changing my attitude making it “worth it”, really? So if people don’t change or think about their attitudes, the whole show was worthless? Nah…

BTW, if you really want to think about nudes in today’s era, spend some time with the recently deceased Lucian Freud. Start with Big Sue.